Was the 1917 Bolshevik seizure of power inspired by an uprising in Ireland?

Boris Kustodiyev, Bolshevik, 1920, oil on canvas, State Tretyakov Gallery.

Global Look PressStriking a blow against empire

In 1917, amid the chaos and carnage of World War I, Russia was the first great European empire to fall. Less well known is the fact that the previous year a nationalist revolt in Dublin dealt a significant blow to the British Empire, making a strong impression on the October Revolution’s mastermind, Vladimir Lenin.

On the eve of Easter Monday 1916, most European governments were deeply embroiled in a war that put the continent’s imperial order to the test. For many scheming revolutionaries across Europe, the war proved to be the ideal distraction for an armed insurrection.

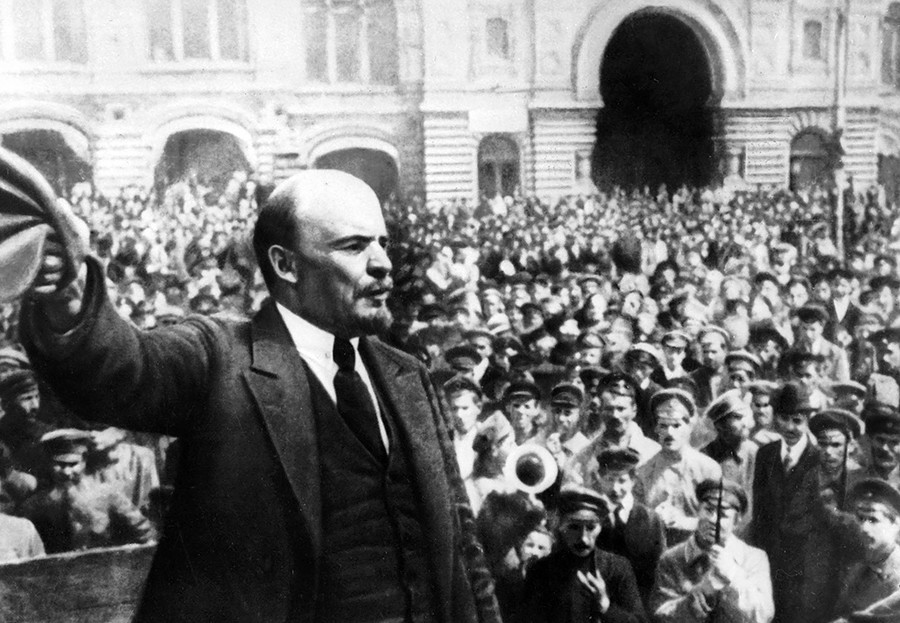

Vladimir Lenin addresses soldiers of the new Soviet army in Moscow’s Red Square on May 25, 1919.

TASSOn April 24, 1,600 Irish rebels took British leaders by surprise with the seizure of strategic buildings across Dublin, proclaiming an independent Irish republic and showing a readiness to fight bloody street battles with the British army. Although the rebellion failed to attract much public support and was eventually crushed, it sent shockwaves throughout Europe and encouraged further revolts while the empires were weak.

Lenin, then-leader of Russia’s Communist Party, particularly admired the rebels’ street tactics and anti-imperialist character and saw the Irish resistance movement as a natural ally of the Communist Party. “The only misfortune of the Irish,” Lenin claimed, “is that they rose too prematurely.”

Lenin’s love affair with Ireland

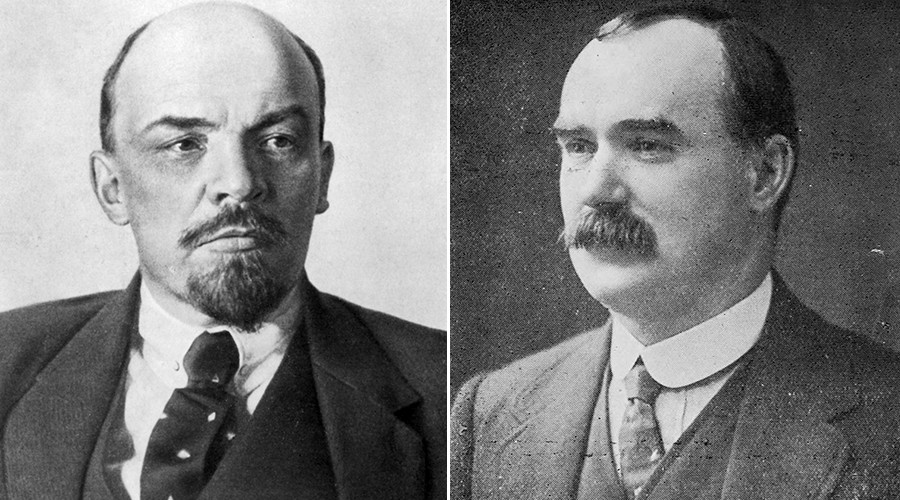

Key to understanding Lenin’s Irish sympathies was his relationship with Irish socialist leader James Connolly, one of the architects of the Easter Rising, and who was executed by the British Army in 1916, shortly after the insurrection. The pair is reported to have exchanged letters often, and when Lenin welcomed Connolly’s son, Roddy, at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg in 1922, he declared Roddy’s father “head and shoulders” above all other European socialists. Roddy was even dubbed the son of the “Irish Lenin” in the Soviet press following the meeting.

Lenin and Connolly.

Wikipedia/Global Look PressDuring his visits to London while in exile between 1902 and 1911, Lenin learned to speak English with a convincing Irish accent. According to author H.G. Wells, Lenin hired an Irishman as his English tutor to save on costs, giving the future Soviet leader a “distinctive Dublin twang.”

Ideological difficulties

Largely due to his close relationship with Connolly, Lenin understood the Irish nationalist cause well, leaving him at odds with his Russian comrades. To most Russian Marxists at the time, the Irish question was a complex

In order to help Russians understand the issue, Soviet history books later used “Red Easter,” the red/white vocabulary of the Russian Civil War to explain the rebellion - the British army became the “Whites,” and the Irish were the “Reds.”

Of course, the situation was more complex – apart from Connolly, the rebels mostly identified as nationalist rather than socialist, contradicting Communist internationalist principle. Trotsky dismissed the Dublin rebels as “nationalist dreamers who ensured the preponderance… of the green flag over the red.” German communist Karl Radek also derided the revolt as a “petty bourgeois putsch.”

Lenin, however, welcomed Connolly’s brand of socialist nationalism, and indignantly defended the Irish struggle within Marxist circles. Responding to Radek, he claimed that, “those calling the Irish rebellion a ‘putsch’… hold such a ridiculously pedantic view,” and those expecting a “’pure’ social revolution…will never live to see it.”

Agreeing with Connolly’s argument that national self-determination was necessary for colonies to establish a socialist framework, Lenin, ever the

To Lenin, Ireland’s agrarian economy was reminiscent of Russia’s – he preached the need for an urban proletariat to spread Communism to the peasant class of both countries. Drawing from Connolly’s attempts to reconcile republican and socialist concerns through nationalism, Lenin looked to appease the Russian

From theory to revolution

The Easter Rising set the process of Irish independence in motion, but unlike in Russia, mass union-led uprisings across Ireland were kept to a minimum – with the exception of the Limerick Soviet in 1919.

Royal Irish Rifles at the Battle of the Somme,1916.

Global Look PressNonetheless, the revolt sent shockwaves across Europe and demonstrated the potential impact that a small and determined militia could have on any of the empires bogged down in war. In 1917, Lenin wrote in The State and Revolution that in a revolution, subordination to a “small, armed vanguard of the proletariat” is essential to strike the imperial order in a disciplined and efficient manner.

Were the Irish rebels the perfect template for this “vanguard”? When Leninist ideology prevailed in the overthrow of the Tsarist regime, there were, in fact, some similarities between the immediate seizure tactics of the October Revolution and those of the Easter Rising. Much like Irish rebels, the Bolshevik insurrection began without a wider public mandate; it was the result of an executive decision within the Petrograd Soviet.

More importantly, both risings involved the seizure of public property - before the much eulogized storming of the Winter Palace, the pro-Soviet soldiers swiftly and bloodlessly seized strategic control centers throughout St. Petersburg, just as the Irish rebels famously seized the General Post Office in Dublin.

Once this was achieved, both insurrections were followed by proclamations of new states – be it Patrick Pearse’s Proclamation of the Irish Republic, or Lenin’s To All the Citizens of Russia – that were read to surprised crowds in full knowledge that powerful backlashes would ensue.

Russia and Ireland certainly differed greatly in the early 20th century, and whether or not Lenin modeled the October Revolution on the Easter Rising, there are both practical and ideological parallels between them. Lenin’s sympathy with the colonial struggle of small nations allowed him to picture the Russian proletariat as an oppressed nation in its own right, acting in its own self-interest. Without the example of the Easter Rising, the course of the October Revolution, and therefore the course of history, might have been completely different.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox