Was the Romanovs’ murder ritualistic? 3 mysteries of the royal family's deaths

Family of the tsar Nicholas II

Vladimir Boiko/Global Look Press1. 'The codified message'

“We are very serious about this version of a ritualistic killing. Many members of the Church commission [for the Romanovs’ murder investigation] have no doubts that the killing had a ritualistic character,” Bishop Tikhon, an influential Russian Orthodox Church official, said at the conference devoted to the royal family’s demise.

This statement made quite a stir since some interpreted it as a hint of anti-Semitic nature about those tragic events, which is why Bishop Tikhon offered some clarifications. As he pointed out, “even after his abdication, the emperor remained a symbolic and sacred figure.” “Bolsheviks and their different supporters were not at all alien to completely unexpected and varied types of symbolism”, he said.

The basement of the Ipatiev house where the Romanov family was killed

Global Look PressHe vehemently denied any anti-Semitic interpretations of his words. But the phrase “ritual killing” was bound to stoke comments despite the bishop’s objections. It is due to the fact that the version of the ritualistic murder was proposed soon after the killing and at the time it had a clear anti-Semitic flavor.

It originated among those who in 1919 were given the task to investigate the royal murder. Investigators were drawn from the ranks of political opponents of Bolsheviks, the Whites. British journalist Robert Wilton, who was close to the investigation, wrote in his book, published a few years later, about “cabalistic inscriptions” [i.e those pertaining to occultist esoteric rituals originated in Judaism] found in the basement of the house in Ekaterinburg where the Romanovs were killed. Those inscriptions were: “1918 года” [the year of 1918], “148467878 р” and “87888”. As it turned out, they were really documented in the course of the investigation.

The investigators, however, did not pay attention to them. That was not the case with the Russian emigre Mikhail Skaryatin. In the mid-1920s he declared that he had managed to decipher those symbols. He claimed they contained a hidden message: “Here, by the order of secret forces, the Tsar was sacrificed for the destruction of Russia. All nations are informed about this.” The “secret forces” in this case stood for the Jews who allegedly aspired to chaos and consequent world domination. This “discovery” was later popularized by those circles in Russian emigration, who were sympathetic towards the Nazis.

2. Speculation about beheading

Closely connected with the “ritualistic killing” story is another one that remains discussed to this day, and is even more gruesome. It touches upon what happened to the bodies of the murdered royals. For decades they were not found. It was rich ground for different rumors and terrifying legends. The chief of the investigation commission organized by the Whites, Mikhail Ditrikh, writing in 1922 claimed there was speculation that members of the royal family had been beheaded after they were shot. Their heads were put in big jars and transported to Moscow, to the Soviet leadership. Later investigations and forensic expertise proved this theory wrong.

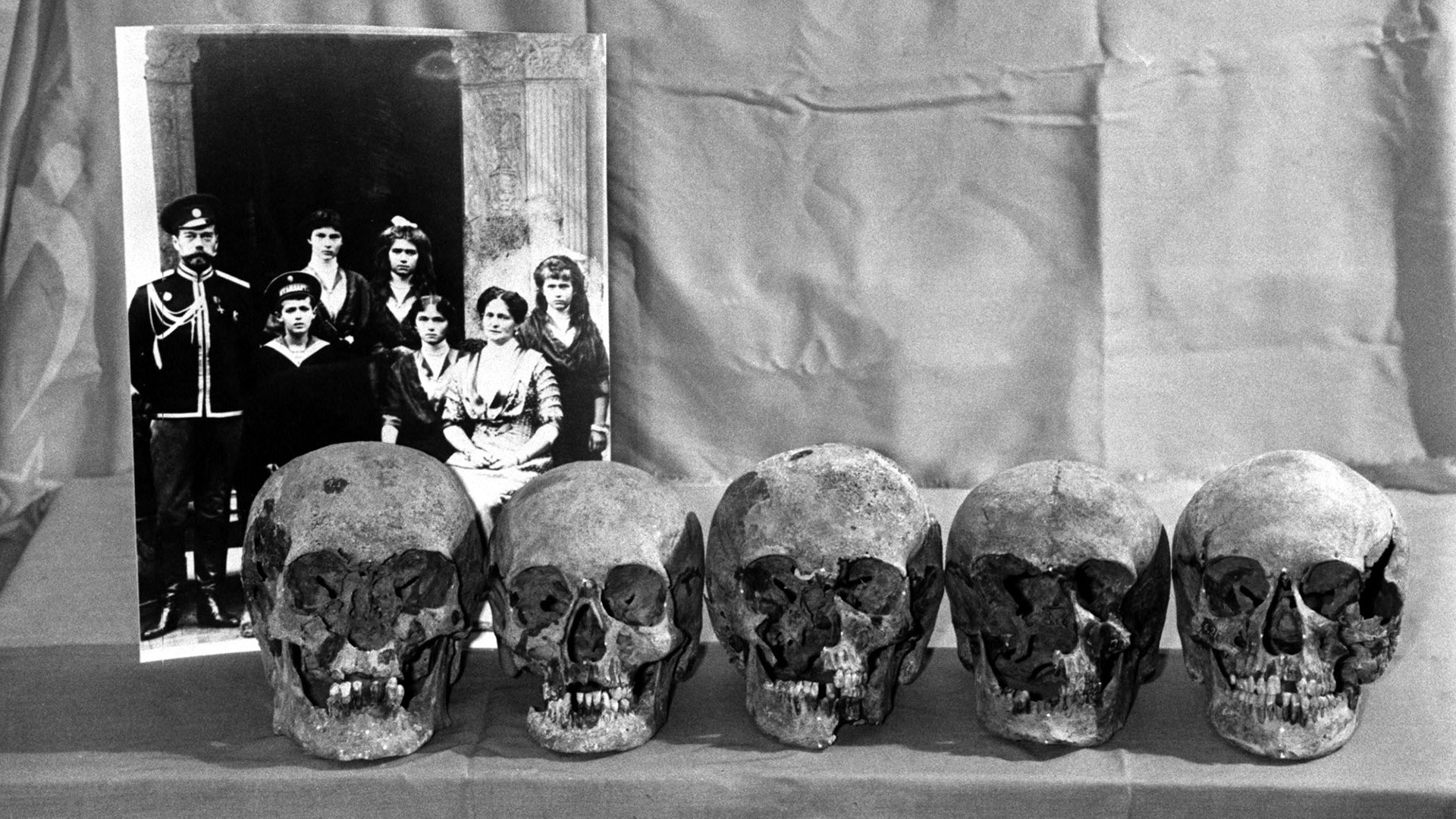

The skulls that supposedly belong to the killed Romanov family members

Anatoly Semekhin/TASSAt the same time, the Church has not yet recognized the remains found in 1991 as those belonging to the Romanovs. Moreover, the Investigative Committee of Russia has pledged to study the version of the ritualistic murder. Hence, it is too early to draw the line in what concerns the killings and accompanying circumstances.

3. Who gave the order?

Almost a hundred years after the killings, it is not yet known who actually gave the order to shoot the royal family. Was it Lenin's decision or a local initiative of radical Bolsheviks in Ekaterinburg?

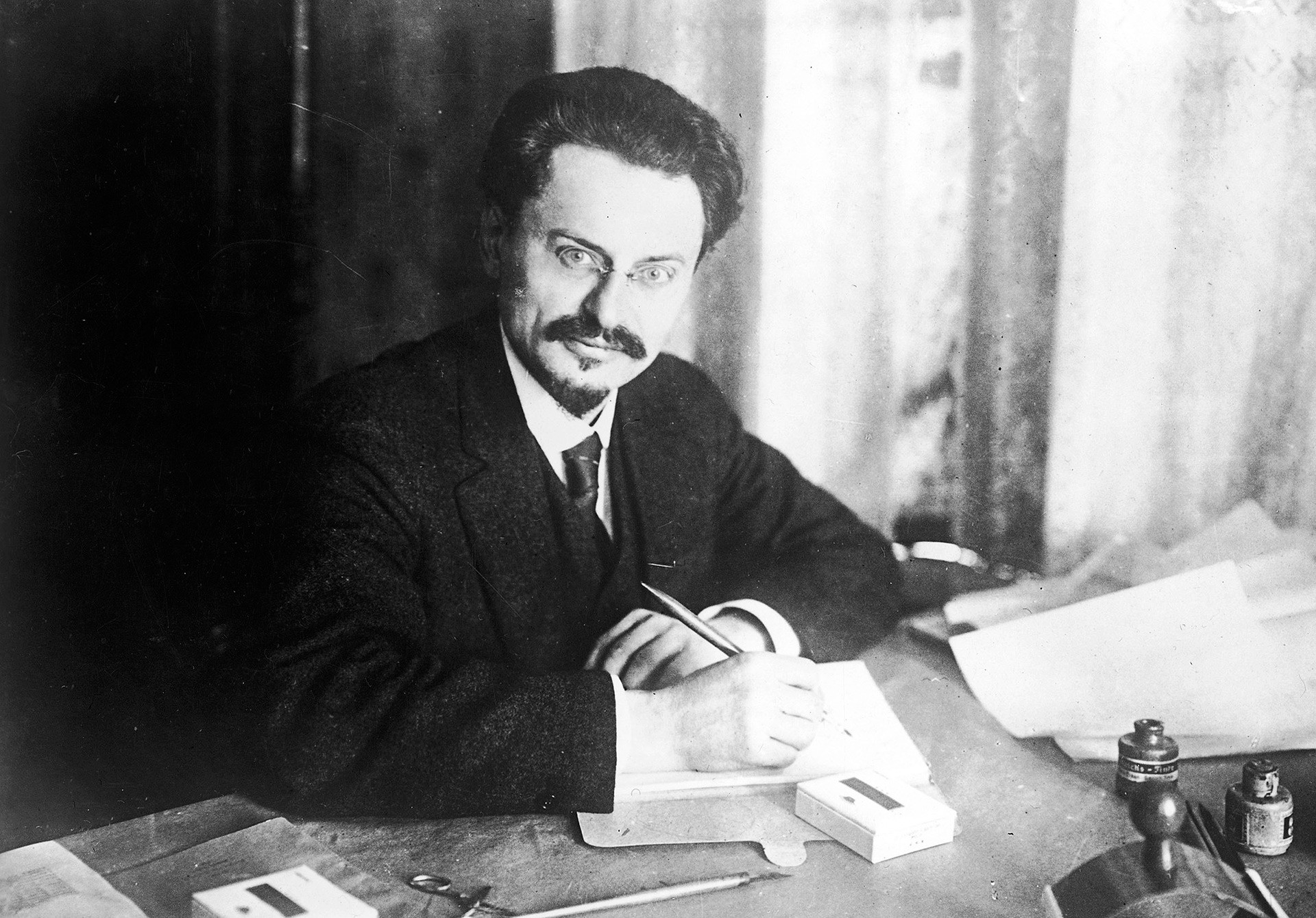

Leon Trotsky

Mary Evans Picture Library/Global Look PressResearchers who think the former is true usually refer to Leon Trotsky’s diaries of the mid-1930s. He was second only to Lenin in the young Soviet Republic and wrote how he asked Lenin’s associate Yakov Sverdlov what happened to the tsar. He was allegedly told that the emperor was shot dead together with his family, since such was the decision taken in the Kremlin. Trotsky, who was famous for resorting to extremely harsh measures during the civil war, hinted in his writings that he was surprised by the severity of this action. However, according to the existing protocols of the government’s session, he was present at the gathering of July 18 [the next day after the killing], when high-ranking communists were informed about the tsar’s murder. So, he had to know what happened to the tsar, and thus it casts doubts on his testimony.

There is also evidence that the Bolsheviks initially planned to stage a trial of Nicholas II and as such they were not interested in his unlawful killing. It is argued however that by mid July 1918 the situation changed, Ekaterinburg was about to be taken by Bolshevik opponents, and Lenin could have feared that the deposed tsar would become a rallying point for anti-Bolsheviks. However, as historian Genrikh Ioffe asserts, those anti-Bolsheviks forces were not monarchists. “[They fought under] the banner of democracy, not the restoration of the monarchy.” In this context the tsar was not useful at all, and was not a “sacred and symbolic figure” as Bishop Tikhon argued. “Nicholas himself and the dynasty were much compromised before the revolution… nobody seriously thought about their return” Ioffe contends. This makes it more probable that the order authorizing the killing of Nicholas and his family was given by local communists.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox