What’s unique about bribery in Russian history?

Bribery is not a distinctively Russian phenomenon. It is and has been prevalent in many countries and, on some level, is probably a natural tendency in human nature.

Yet, in Russia there have always been some unique features when it comes to corruption. The most prominent of these is probably the unique system of kormleniya (“feeding” in Russian) that formed as early as the Russian government itself. Governing Russia’s vast territories was a complex task as it was physically hard to pay officials salary in distant regions and was easier for local authorities and law enforcement bodies to exchange their services for goods produced by the public as back then, barter was more common than using money for most transactions.

Nowadays, this practice would be considered a system of bribery, but back then it wasn’t and quickly became a tradition. At that time – in 14-15th centuries — state services weren’t seen as a state funded activity, but rather as a public one. State employees received practically no salary from the state, and so offerings from the public were their main source of income.

If we delve deeper, there were many different types of bribes: pochest (offerings before a particular deal), pominki (offerings after a deal is done) and posul (the promise of a bribe for a court’s decision in one’s favor). Only the last of these was formally considered illegal.

In such a situation, differentiating between the legal and illegal actions of local authorities was often difficult, and the central apparatus failed to control everything that happened throughout the country’s many different provinces. In some particular cases, there were thorough investigations, but this mostly just happened when officials tried to demand more than the public was used to giving.

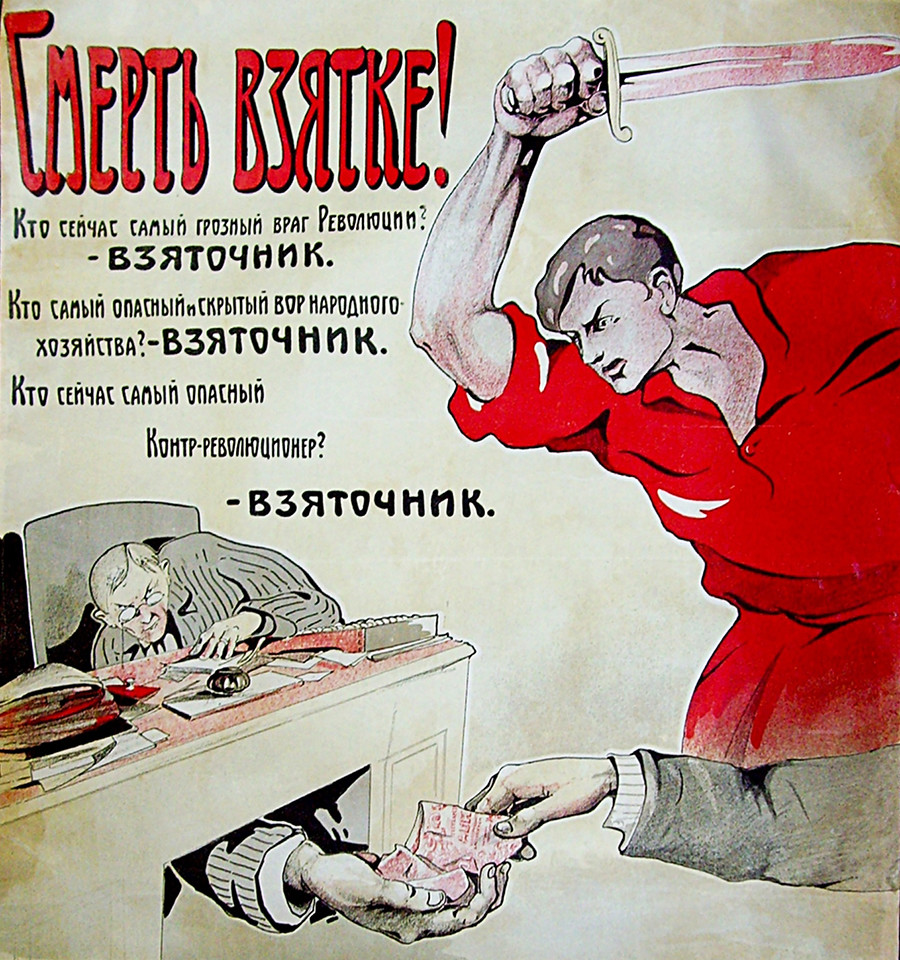

Despite many attempts by Russia’s rulers, from Ivan the Terrible to Joseph Stalin, to eradicate this practice, it has somehow survived throughout Russia’s history and remains deeply branded in the mentality of the people to this day.

Here we choose six famous bribery cases that illustrate the history of corruption in Russia before the collapse of the Soviet Union.

A goose stuffed with coins

The first person to lose his life due to corruption was a deacon who was caught accepting a fried goose stuffed with coins as a bribe. He was brought to the market square and quartered. This happened in 1556, a few years after Ivan the Terrible introduced the death sentence for bribery in 1550. After the deacon’s hands and legs were cut off, Ivan the Terrible asked him if the goose was tasty.

Over his 37 years in power, Ivan the Terrible executed more than 8,000 state employees, which accounts for around 34 percent of all the officials who served him.

Anticorruption uprising

Few people know that there was actually an anticorruption rebellion in Russia’s history. Also known as the salt riot, it happened in 1648, during the rule of Tsar Alexis I (1645-1676), and was provoked by an increase in taxes and a subsequent increase of the price of salt. The rebellion led to the public killing of two corrupt officials – Petr Trakhaonitov and Leonty Plesheyev.

As heads of two law enforcement bodies (called prikaz), they were widely loathed by the public.

Plesheyev took bribes from those whose cases he ruled on in court and created a group of informers that leveled false charges against innocent people who were then put in jail in an attempt to extort money from them. Trakhaonitov, for his part, was infamous for the ruthless treatment of employees, including not paying them a salary.

Punishing the punisher

During the rule of Peter the Great (1689-1725), the fight against corruption was also a major priority. One illustrative story is the case of Alexey Nesterov, an ober-fiscal in charge of secretly surveying the work of the state apparatus and finding out about corruption. After informing the tsar about a governor in Siberia who allowed the illegal tobacco trade and the subsequent execution of this governor in St. Petersburg, Nesterov himself was caught up in corruption charges.

After being denounced, he was tortured and admitted that he had accepted bribes in the form of money and goods from various people in order to get them positions in the state apparatus. He also took money from alcohol producers. The tsar himself watched the execution. Nesterov’s two most senior subordinates were executed before he was tortured with a Catherine wheel and then beheaded. The heads of the convicted were stuck on iron spears, and their bodies were attached to wheels.

Sent to Siberia

Catherine II was another ruler who attempted to root out corruption in the country, although one account suggests her attitude towards it was less ruthless than that of her predecessors. “Our heart shuddered when we heard that some registrar, Yakov Renberg, took money from every person who was brought in to swear allegiance,” she wrote. “We sent Renberg into eternal exile and hard work in Siberia – only out of mercy. For such a grave violation of the law, justice demands he be punished with the death sentence.”

Corruption in the provinces

19th century memoirs provide many firsthand accounts of giving or receiving bribes. One such account is a document on bribery in the Perm province from the archives of the Golitsyns, a Russian noble family that had an estate there.

Their records show even the nobles couldn’t avoid paying the authorities – further evidence that this was a widespread and longstanding tradition. In the beginning of the 19thcentury local officials for the most part took bribes in the form of natural products like flour, bread, sugar, fruits, wheat and other things. Later on, in the middle of the century, such public offerings to the authorities mainly consisted of money. The Golitsyns made such payments to the majority of the local statesmen over the years, ranging from province officials to the courts, which often accounted for a large share (37-38 percent) of such expenditures.

The Cotton Case

Corruption existed in the Soviet Union as well, and there were positions in the state apparatus that allowed for making easy money. Under the strict rule of Joseph Stalin, corruption was reduced somewhat but then came back and continued to flourish. One of the most famous examples was the Cotton Case – also called the Uzbek Case – which had to do with 18,000 people who gave and received bribes.

Overall, 800 criminal cases were examined, with more than 4,000 people being sent to prison as a result. This huge corruption case centered on cotton that the Soviet republic of Uzbekistan supplied throughout the Soviet Union. It turned out that trains thought to be transporting cotton of highest quality were, in fact, often either empty or filled with low-quality product. Uzbek officials paid off those who were supposed to be receiving the cotton orders and took Kremlin money in return for the fictitious deliveries.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox