'Bolsheviks are crocodiles': How Churchill maintained a love-hate relationship with the USSR

Winston Churchill (1874-1965), the First Lord of the Admiralty, arriving at Downing Street, where the War Cabinet met to discuss Russia's intervention in Poland. Picture taken in 1939

Daily Herald Archive/NMeM/Global Look PressAnyone familiar with the history of the 20th century knows Sir Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom 1940–1945 and 1951–1955, not only for his political heritage but also for his eloquent speeches. Such examples of oratory as “We shall fight them on the beaches” or “This was their finest hour” inspired Britain during the harshest times of WWII, helping the population to withstand the Blitz.

Nevertheless, long before the Nazis came to power in Germany, Churchill had another archenemy. A conservative politician, he had hated Bolshevism since 1917, calling Vladimir Lenin “a culture of typhoid” smuggled into Russia. The Communists had no warm feelings for Churchill either.

For instance, Leon Trotsky called him “a champion of capitalist violence” eager to choke proletarian masses struggling for their freedom. Throughout his political career, Churchill continued to criticize the USSR – and only in the face of a common threat did the enemies unite their efforts.

“If Hitler invaded hell…”

Pro-Nazi caricature showing Winston Churchill weighed down by the Communist hammer and sickle, symbolizing his alliance with Russia.

Getty ImagesAt the beginning of WWII, between 1939 and 1941, Churchill, appointed Prime Minister in 1940, remained cautious in his comments on the USSR. No one knew which side Moscow would end up on. In October 1939, soon after the Soviet invasion of Poland, Churchill pronounced perhaps his best-known commentary on Russia: “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

In two years, the situation cleared up. On June 22, 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the USSR and from now on London and Moscow were in this together. Decisive as he was, Churchill immediately showed support for the Soviets. The reasons were clear. “If Hitler invaded hell I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons,” the Prime Minister told his secretary.

New bonds

Publicly, Churchill chose more respectful words. In his address to the nation on June

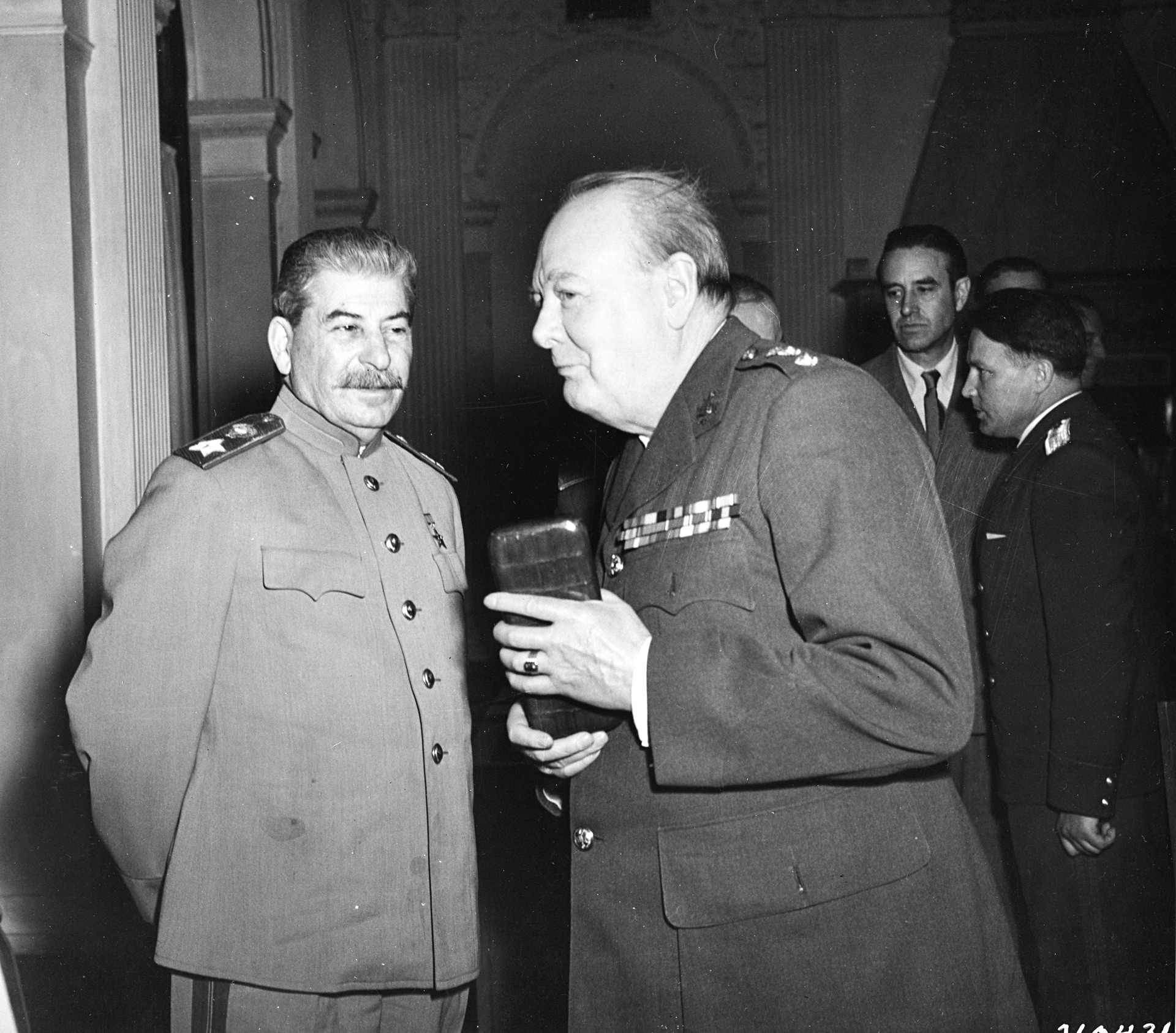

Years of fighting would lead both the USSR and Britain, along with the U.S., to victory. Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill at the Yalta Conference held at the Livadia Palace, Livadiya (near Yalta), Soviet Union (later Ukraine), February 1945.

Getty ImagesBack then, many British politicians and the military showed skepticism towards the USSR’s perspectives, predicting that Russia would last for

In less than a month Britain and the USSR signed the Anglo-Soviet Agreement, pledging to assist each other in the fight against Hitler. Nevertheless, tensions remained between the parties – especially concerning the issue of opening the second front in Europe.

Tough Alliance

Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill sit in the Kremlin in Moscow.

Getty ImagesUnlike Franklin D. Roosevelt, Stalin was never a convenient negotiation partner for Churchill. When the Prime Minister traveled to Moscow in August 1942 in order to inform Stalin of Britain’s plans to attack Germany in Africa rather than in Europe, the Soviet leader initially denounced the Allies for cowardice and failing to keep their promises.

The leaders found mutual understanding only on the third day of talks when they sat alone in a tiny room and drank heavily. As Sir Alexander Cadogan, a high-ranking British diplomat, recalled, “I found Winston and Stalin … sitting with a heavily laden board between them: food of all kinds and innumerable bottles.”

Next day Churchill, who had been drinking Caucasian wine, unlike poor Cadogan whom Stalin forced to drink something “pretty savage”, presumably left Moscow with a headache but also with satisfaction – Stalin agreed to wait for the second front to be open.

Honeymoon comes to an end

British troops taking part in an Allied Victory Parade in Berlin rest beneath a large poster of Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at Yalta. Soon after winning the war, the relations between the Allies deteriorated all over again.

Getty Images“He did say laudatory things about Stalin during the war, notably in 1942,” Richard M. Langworth, a historian specializing on Churchill, admits. Indeed, after his Moscow visit the Prime Minister called Stalin a “great rugged war chief” that the USSR was lucky to have in a time of war.

This, however, never meant that Churchill liked Stalin or changed his view on Communism. “Never forget that Bolsheviks are crocodiles… I cannot feel the slightest trust or confidence in them,” he wrote to Anthony Eden in 1942.

Soon after the war ended, in March 1946 Churchill (no longer Prime Minister) delivered his famous “Sinews of Peace” speech in Fulton, Missouri, where he expressed “sympathy and goodwill” in Britain towards Russia but at the same time warned against Communist influence spreading around the globe, noting the spread of Soviet influence in Europe: "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent." The speech from such an outstanding politician became kind of a landmark – soon after the former allies turned into rivals. The Cold War was about to start.

In case you’re eager to know more about the different aspects of the Cold war, check out our story on why the USSR lost the moon race to America.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox