The fearsome Red Machine: The meteoric rise and dramatic decline of Soviet hockey

1.

Before 1946, Russians didn’t know a thing about ice hockey. While bandy was the most popular winter sport in the country, ice hockey was gaining international popularity thanks to its inclusion at the Olympics. So, Soviet sports officials tasked bureaucrat Sergey Savin with a surprising mission: to study the unknown game and see if it has any potential. Savin went to Latvia where he obtained Canadian-made ice skates, a stick, a puck, and a set of hockey rules published in Latvian.

2.

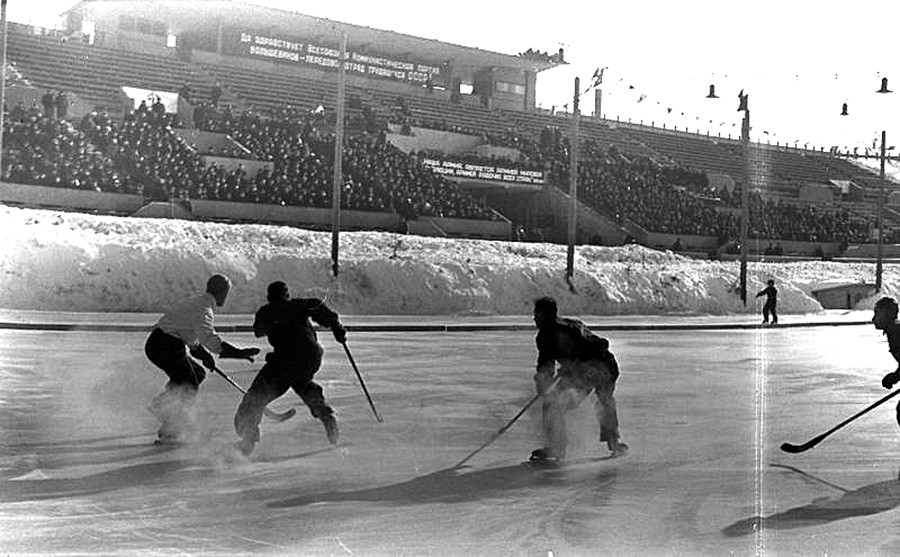

Hockey needed to be tested in public to see if the Russian people had any interest in the new game. After the end of a bandy match in November 1946 in Moscow’s Petrovsky Park, the spectators remained in their seats. Organizers promised a curious new show: an ice hockey match. The two teams fielded university students who could hardly handle their sticks.

3.

The first official ice hockey match was played on Dec. 22, 1946.

4.

In 1947, Moscow’s Dynamo ice hockey club was the USSR’s first-ever ice hockey champion.

5.

This is the first-ever Soviet ice hockey national team. In 1954, only eight years after the first match between two amateur student teams took place, Soviet athletes debuted at the 1954 World Championships in Stockholm and won gold, beating Canada to everyone’s surprise.

6.

The unknown team of ice hockey novices beat the uncontested champions by the shocking score of 7-2.

7.

The victory on March 7, 1954, marked the beginning of the legendary hockey rivalry between Canada and USSR.

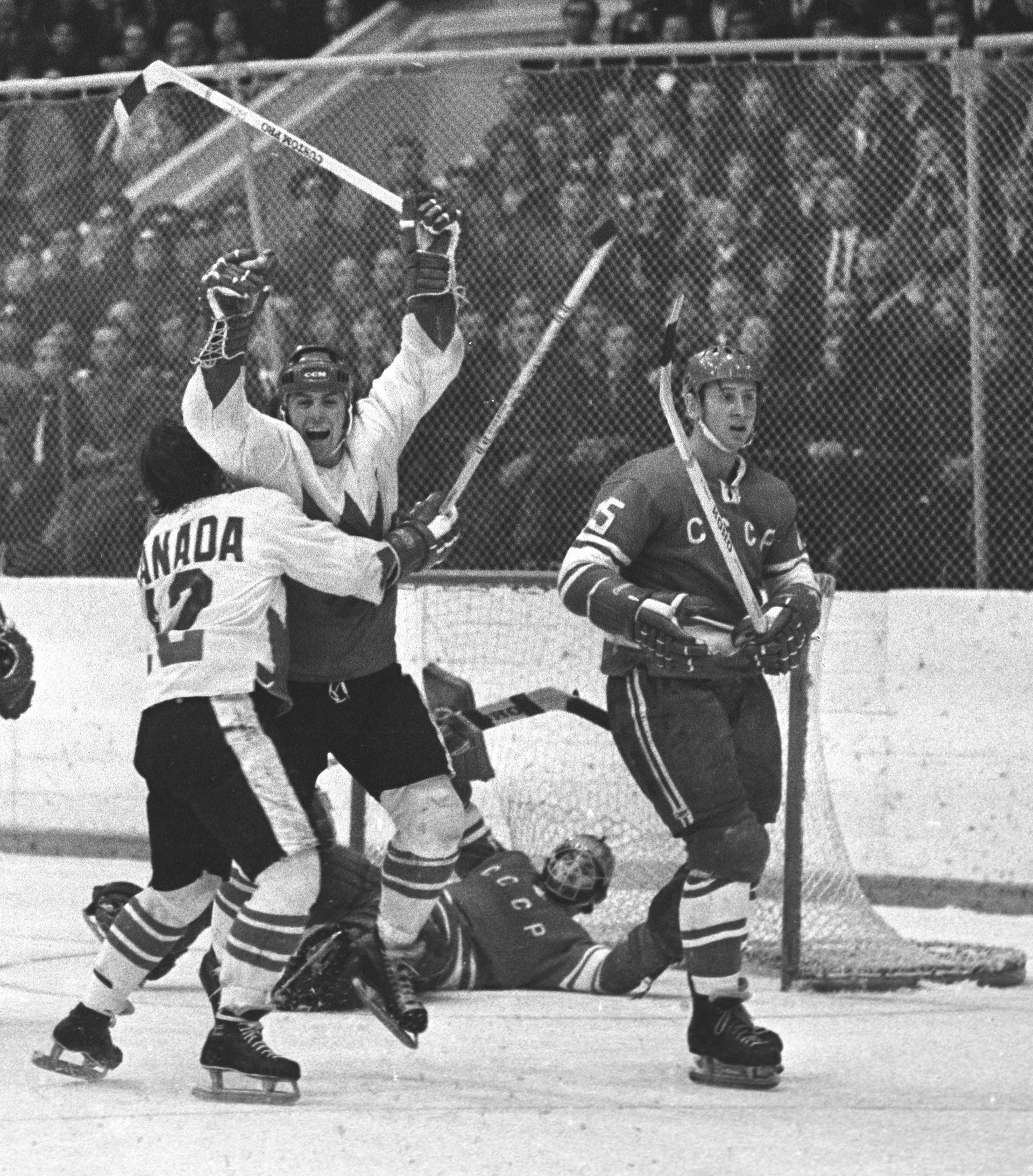

The rivalry reached its peak in September 1972, during the famous Summit Series, aka the Super Series, which consisted of eight games organized in the midst of the Cold War.

8.

Canadians got the upper hand winning the series 4 to 3, with one tie. Paul Henderson scored with only 34 seconds left in the match. The unprecedented rivalry and tension pushed every player on both sides to his limits.

9.

Despite the narrow defeat, the Soviets fought for dominance in the sport in many more championships following the Summit Series. Here are players Valery Kharlamov, Vladimir Petrov and Boris Mikhailov.

10.

Led by legendary trainer Victor Tikhonov, the Soviet national team won 22 gold medals in a series of world championships that lasted from 1954 to 1990, and seven gold medals in various Olympic games between 1956 and 1988. Tikhonov, however, was highly criticized for his harsh, almost military-style training methods.

11.

The fierce competition between the Canadian and Soviet national teams made superstars of its players. Vladislav Tretiak, the team’s goalie became a world-famous star. The Soviet government blocked a move by the NHL’s Montreal to draft Tretiak in 1983. He now serves as an MP in Russia’s State Duma.

12.

The American press dubbed the Soviet national team the “Red Machine.” Mike Eruzione, a captain who led the U.S. national team to victory over the Soviets at the 1980 Winter Olympics, said the Soviets never smiled, not even when they scored. “They were like robots,” said Eruzione. The questionable nickname initially offended some of the players, but later it became a world-famous brand.

13.

The U.S. national team famously defeated the Red Machine at the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York. The victory was dubbed the “Miracle on Ice.”

14.

The Soviet national team ceased to exist with the collapse of the USSR. Today, Russia’s national team is the official successor of the famous Red Machine. Olympic Athletes from Russia represented by a neutral flag, and led by trainer Oleg Znarok, won the gold at the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea.

Click here for the history of Soviet football in pics.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox