Why didn’t the Soviet Union support revolution in Afghanistan?

Red cavalrymen on the march.

Zelma/SputnikLong before the Saur Revolution and the Soviet military involvement in Afghan affairs, Soviet soldiers had already fought on Afghan soil. Secretly, dressed as locals, but with Russian “Hurrah!” cries, they actively participated in the local civil war of the late 1920s.

The political situation in Afghanistan had always been a subject of particular attention for the Soviet leadership, since it directly influenced the security of the neighboring Soviet Central Asia region. That’s why, when in 1929 the local king Amanullah Khan was deposed by revolutionaries and that in turn led to the outbreak of the civil war, the USSR could not stand on the sidelines.

On one side, there were masses of common people struggling against the elite – such initiatives always got the support of the Soviet Union worldwide. Yet on the other, Afghanistan under Amanullah Khan enjoyed good relations with the USSR. Both countries expanded economic and military cooperation, the Afghan sovereign effectively kept in check the Basmachi, Central Asian anti-Soviet rebels who fled to Afghanistan from the USSR during the Russian Civil War and terrorized Soviet territory with their numerous raids. The choice facing Moscow as it sought to take maximum advantage of the situation was tough.

Whom to support?

Surprisingly, the Soviet Union didn’t rush to support the revolutionary masses of peasants led by the “son of a water carrier” Habibullah Kalakani. Georges Agabekov, a Soviet intelligence agent in Afghanistan in the 1920s who defected to the West in 1930, says that opinions were divided on which side the USSR had to choose in the ongoing conflict (Georges Agabekov, “OGPU: The Russian Secret Terror,” 1931).

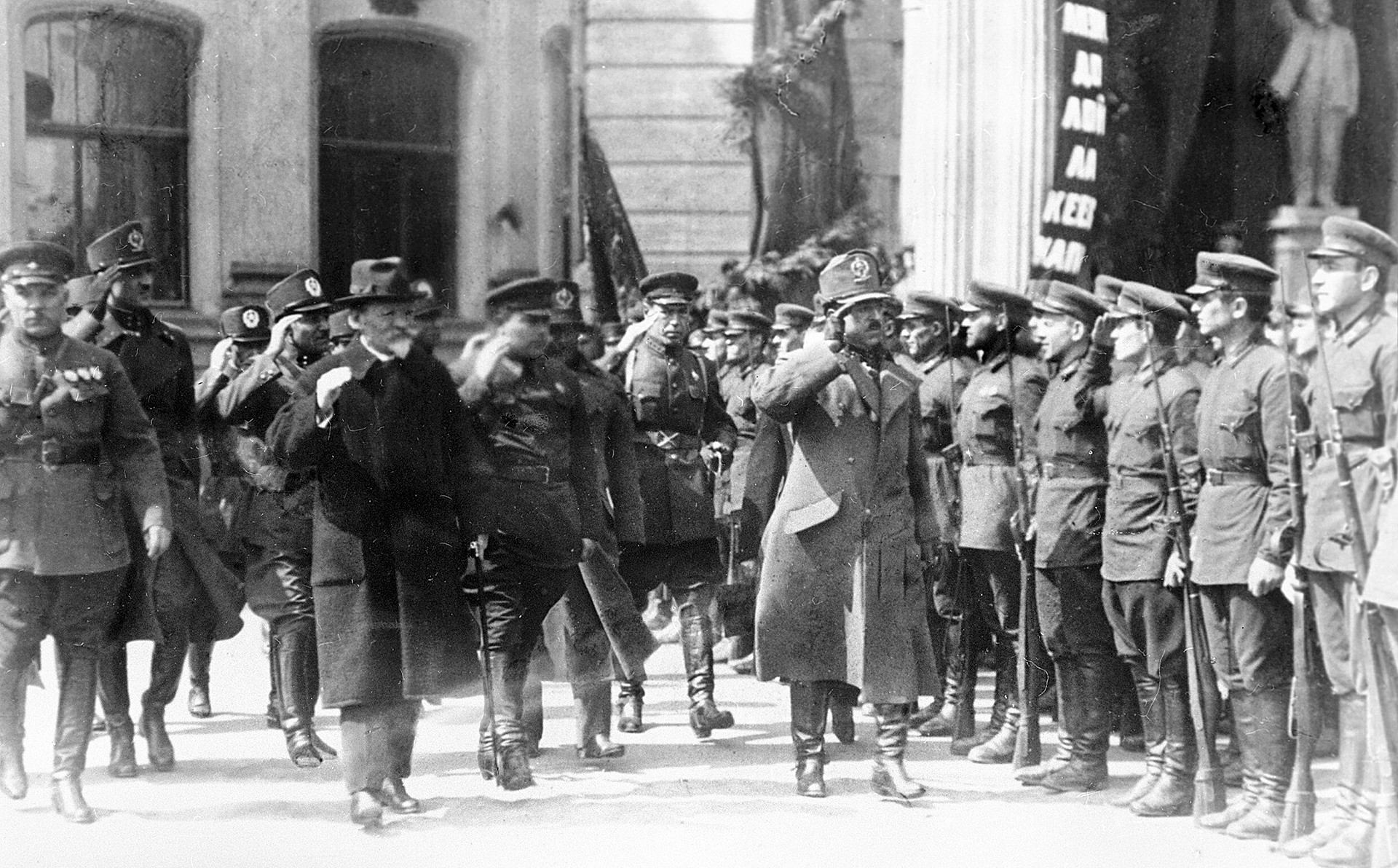

President of the USSR Central Executive Committee Mikhail Kalinin (left) and Afghan emir Amanullah Khan (right) reviewing a guard of honor during the emir's visit to the Soviet Union.

SputnikThe Soviet OGPU secret police, the predecessor of the future KGB, urged support for the revolutionaries, who represented the broad populace. The OGPU supposed that supporting Habibullah would help Sovietize the whole of Afghanistan, Agabekov says.

An opposite opinion was expressed by the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs (since 1946 – the Soviet Foreign Ministry). Diplomats said that Habibullah Kalakani, an ethnic Tajik, had the strong support of the millions of Tajiks that lived in the northern part of Afghanistan, in immediate proximity to the USSR. According to the Commissariat, if Habibullah won and strengthened his power, he would inevitably try to expand his influence on the Soviet Central Asian republics and destabilize the Soviet-Afghan border.

The Soviet diplomats’ words turned out to be true – Habibullah made an alliance with Basmachi leader Ibrahim Bek, and the Basmachi raids into the USSR significantly increased. The other factor against Habibullah was that he was actively supported by the British. Thus, the Soviet leadership chose to help Amanullah Khan with troops and bring stability back to the region.

Secret campaign

The Soviet Union didn’t want to openly demonstrate to the world its military involvement in the civil war in Afghanistan. The more than 2000 Red Army soldiers who took part in the Afghan campaign were dressed as Afghan soldiers. They were led by former Soviet military attaché in Afghanistan Vitaly Primakov, who pretended to be a “Caucasian Turk,” officer Ragib-bey.

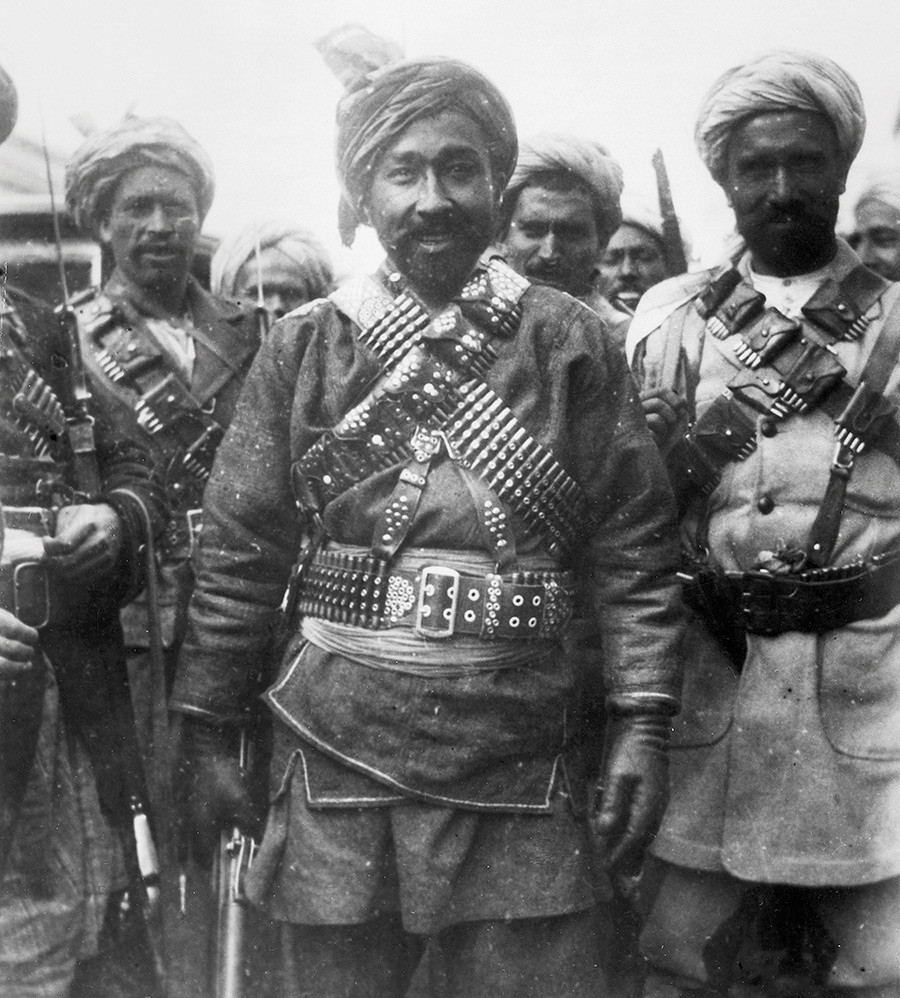

Habibullah Kalakani.

Getty ImagesThe unit was accompanied by the Afghan council in the USSR, led by Ali Gholam Nabi Khan, who gave it legal status. The council pretended to be a unit of Amanullah’s supporters who had been forced to leave the country and now were ready to go back and fight for their king.

Well-equipped, armed with machine guns and artillery, the military unit entered Afghanistan on April 15, 1929. With air support, the unit smashed the Afghan border troops and advanced further into Balkh Province to the major city of Mazar-i-Sharif. Simultaneously, the deposed sovereign Amanullah Khan left Kandahar, where he hid after fleeing from Kabul, and with 14,000 troops headed towards the Afghan capital, occupied by Habibullah.

During the storm of the city, the Soviet soldiers forgot that they had to pretend to be Afghans, and went on the attack with Russian cries of “Hurrah!”

After Mazar-i-Sharif was taken, the Afghans called for a jihad against the invaders and blockaded the Soviet troops in the city. To help Primakov’s soldiers, a second unit of 400 men led by “Zalim Khan” (Soviet cavalry commander Ivan Petrov) went into the country.

A group of the OGPU officers with captured Ibrahim Bek (center), leader of the Basmachi rebels.

SputnikThe joint Soviet forces successfully lifted the siege, terminated Habibullah’s national guard and Basmachi units, and rushed through the city of Balkh towards Kabul. However, on May 22 news broke that Amanullah’s troops had suffered a disastrous defeat near Kabul and he himself had fled the country. Any reasons for the Soviet troops to stay in Afghanistan were gone, and the unit was urgently called back home.

During the Afghan military operation, the Soviet troops eliminated over 8,000 enemy soldiers and lost 120 men. In the Soviet military documents the operation was mentioned as a struggle against bandits in Soviet Central Asia. It was forbidden to write about this campaign in the historical literature.

Here you can read about how 39 Soviet soldiers held their ground against several hundred mujahedeen during another war in Afghanistan, one that is much better known.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox