Booze politics: How the Beer Lover Party rose and fell in Russia

Vendor on Nevsky Prospekt in Leningrad, 1990, drinking beer.

Yuri Belinsky/TASSThe mid-1990s were a turbulent time in Russia’s politics. In October 1993, armed clashes broke out in Moscow after a conflict between President Boris Yeltsin and Russia’s parliament got out of control. Two months later, the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, led by populist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, won the parliamentary elections. Anything seemed possible.

Young political strategist Konstantin Kalachev, the future leader of Beer Lovers Party, wasn’t a happy man in December 1993. He had run for parliament but lost. “I decided to pour some beer onto my sadness,” he recalls in a conversation with Lenta.ru.

Legend born

Konstantin Kalachev.

Sergei Metelitsa./TASSStanding in line for beer, Kalachev met Dmitry Shestakov, a friend of his who had also run for parliament but failed. The two were drinking beer in Kalachev’s apartment and talking politics. “We decided that there was no decent political party in Russia,” Kalachev says, “and Dmitry said he would only vote for a beer lovers’ party.”

Perhaps the pair drank a bit too much but Kalachev, still quaffing beer, wrote to all the news agencies that the Beer Lovers Party had been created in Russia (yes, it was that easy in the 1990s). The next day he was in the news, calling a press conference and stating: yes, it’s for real. “Screw all serious politics, I want my 15 minutes of fame,” he describes his feeling.

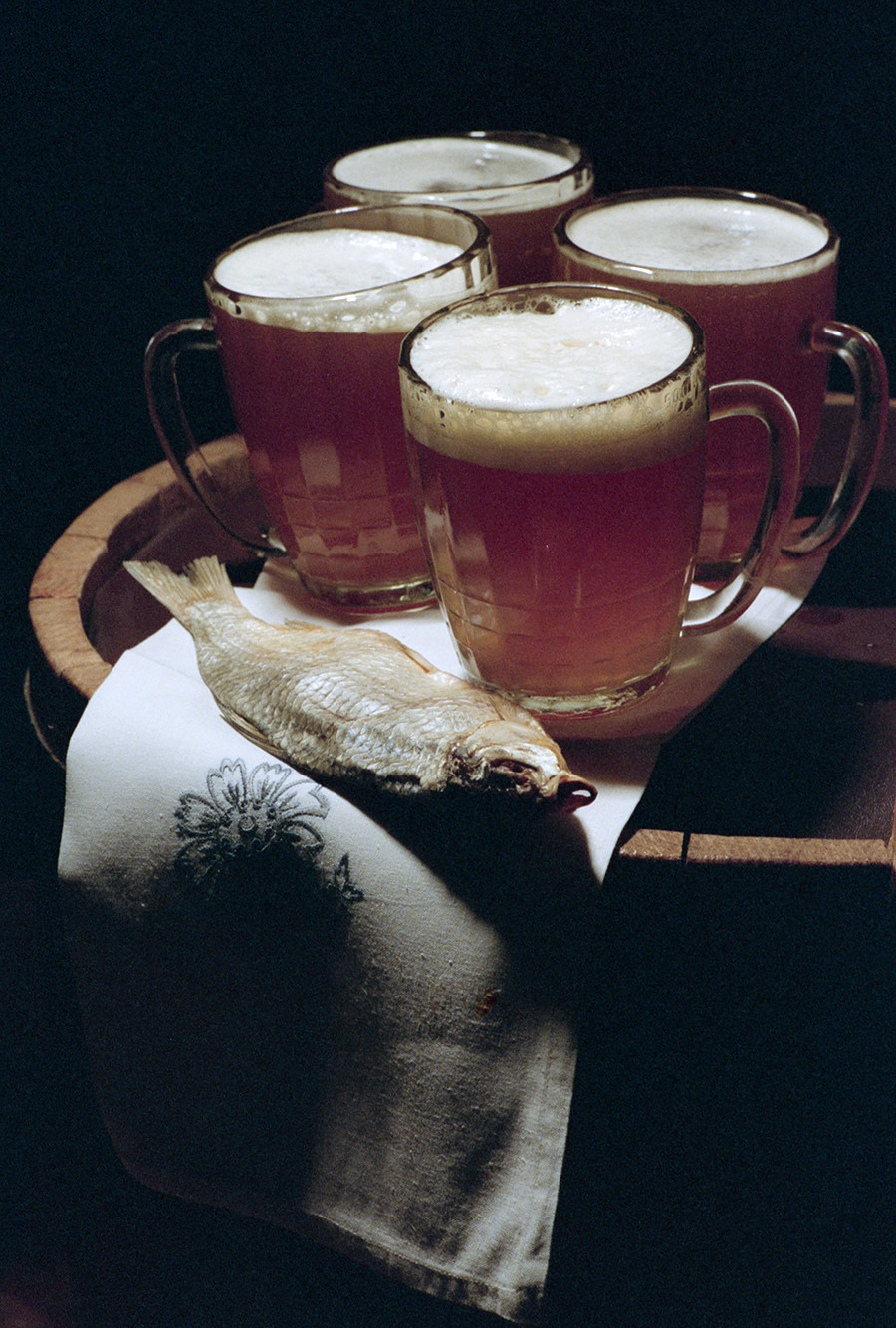

Beer vs. vodka

Beer is something millions of people adore around the world: Russians never were an exception,

ReutersOfficially created in December 1993, the Beer Lovers Party, despite its funny name and connection with the hoppy beverage, had a serious political agenda – or at least claimed to have – and opened its doors not only to beer drinkers.

“The party defends human rights, including the right to drink beer and the right not to drink beer,” the program stated. In terms of politics, the BLP was quite liberal, supporting any kind of political freedoms and “denying any form of authoritarianism”.

“We were opposing the government as the government was controlled, by vodka lovers, I mean Yeltsin,” Kalachev claims. “We said: vodka generates aggression and leads to wars while

That idea wasn’t new: as Russian author Ilya Ehrenburg wrote in his memoirs, even Leo Tolstoy thought that beer might replace vodka for the working class. Nevertheless, neither he nor Kalachev succeeded in promoting such a replacement.

Crazy campaign

Women drinking beer in the early 1990s.

Viktor Akhlomov / MAMMFor the parliamentary campaign of 1995, “Beer Lovers” gathered as much as $300,000 for the campaign and attracted many people, including singer Boris Moiseev, chess grandmaster Vasily Smyslov

Kalachev is proud to say that they offered different options within the BLP: a faction of non-drinkers, a faction of vobla - a type of dried fish - lovers. They even had a “faction for unsatisfied women”. Unsatisfied with the government, officially.

Unsurprisingly, the campaign had a lot to do with beer. The “Beer Lovers” sent a case of beer to Yeltsin and tried to convince Mikhail Gorbachev that beer was the best means to re-unite post-Soviet countries. Their strange campaign videos mocked vodka drinkers and championed peace… through

Bitter defeat

Kalachev and his party didn’t achieve any major success: in the parliamentary elections of 1995, they won only around 430,000 votes – not a big number for such a big country, just 0.62%/. Thus, the “Beer Lovers” didn’t make it to the parliament. “These elegant jokers from the BLP tried to participate in the political auction in vain,” Kommersant wrote.

“Our campaign wasn’t very successful in terms of our message,” Kalachev admits. Among the most harmful mistakes he names disorganization: “Our funds were partly distributed in the regions and our colleagues just spent it and drank away.” What a shame.

The party didn’t last long – in 1998, Kalachev closed the project. He went back to serious (not alcohol-related) politics, working with the United Russia party, which is closely associated with Vladimir Putin. Nevertheless, he seems a bit nostalgic: “I’m not sure if politics was more sincere in the 1990s but it definitely was more interesting.”

There were times when some Russians (Soviets, to be precise) had to drink something far far worse than beer – read our article to find out, what exactly.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox