The USSR’s own Olympics outshone the real thing

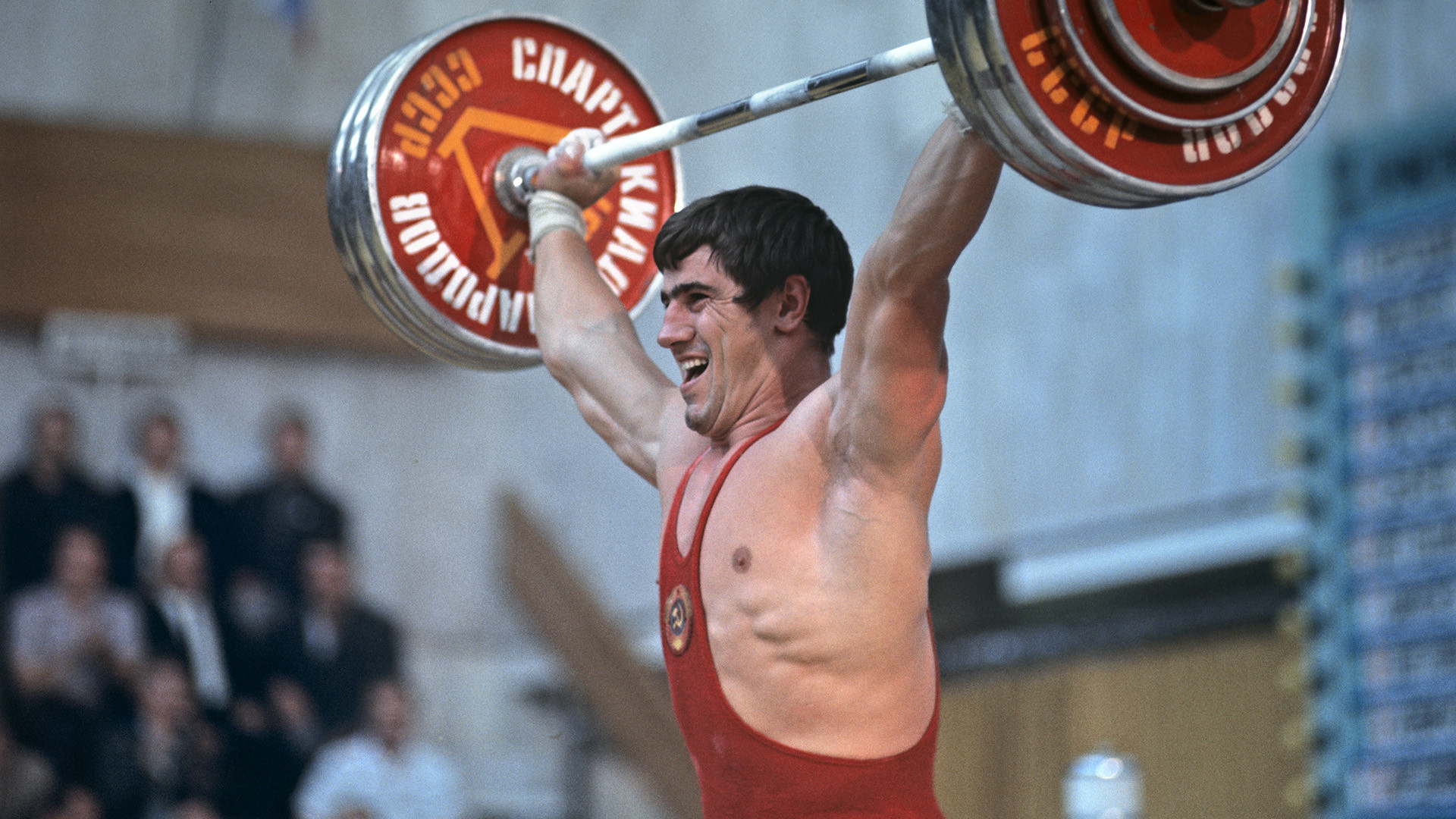

World champion in weightlifting , Honoured Master of Sports of the USSR David Rigert during the Fifth Summer Spartakiad of Peoples of the USSR.

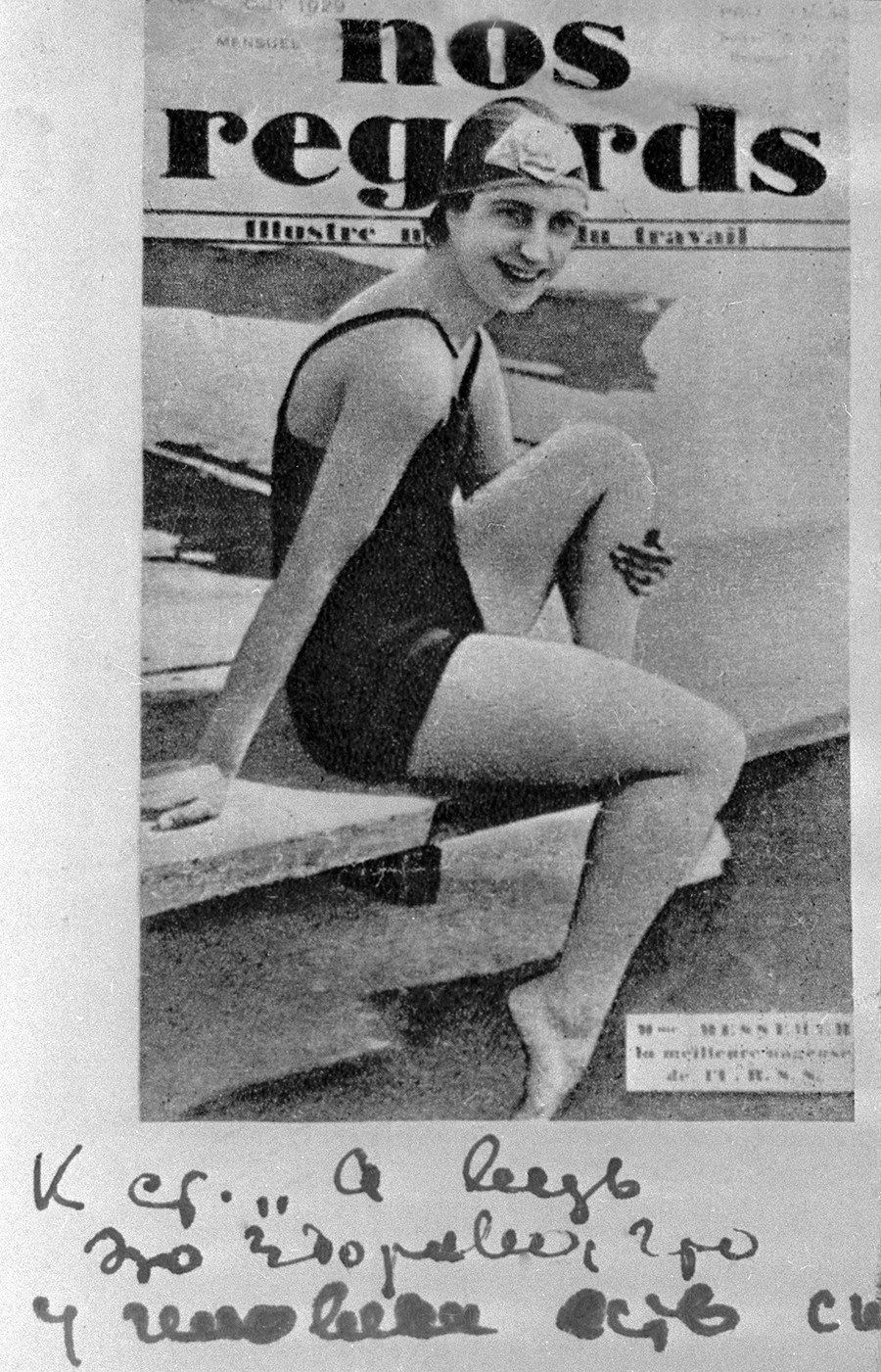

Doliagyn/SputnikThe complicated and hostile relations Soviet Russia had with the majority of the world in the 1920s and 1930s affected sport. The USSR missed every Olympic Games up until 1952. The country was either ignored by the International Olympic Committee, or boycotted the Games itself due to different political and ideological reasons.

The Soviet leadership didn’t plan to isolate the country from the world of international sport, though. An idea was born to establish its own Soviet version of the Olympic Games, which became known as Spartakiade.

A leader of the major slave rebellion against the Roman Republic, Spartacus (or “Spartak” in Russian) became an important symbol in Soviet ideology. In honor of this legendary character plants, streets, sport clubs, and children were named after him. German communists praised Spartacus even earlier and were the first to organize international competitions for workers. The Soviet Union liked the idea and adopted it.

An analogue of the International Olympic Committee was established in 1921 – the Red Sport International, or Sportintern, that regulated workers’ sport around the world.

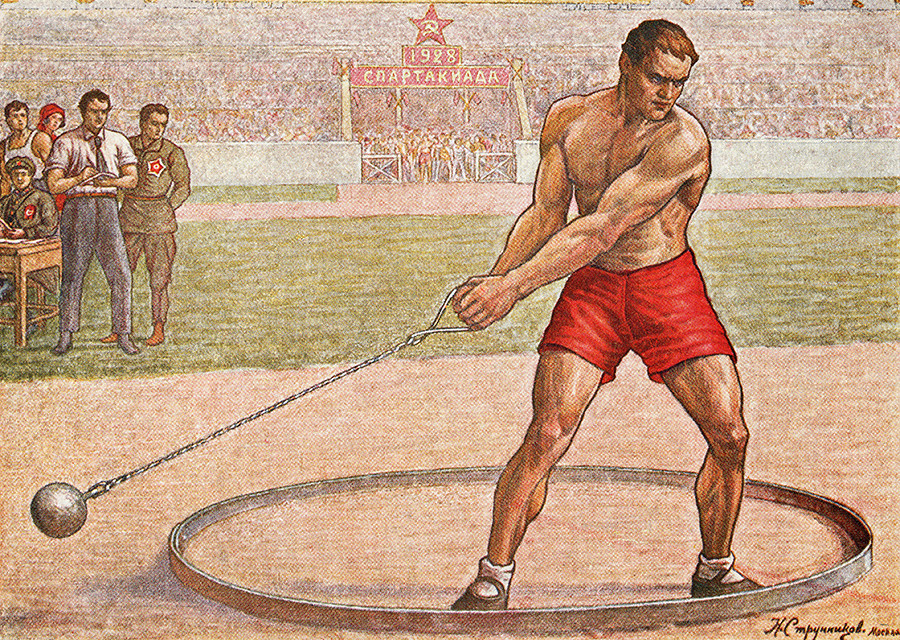

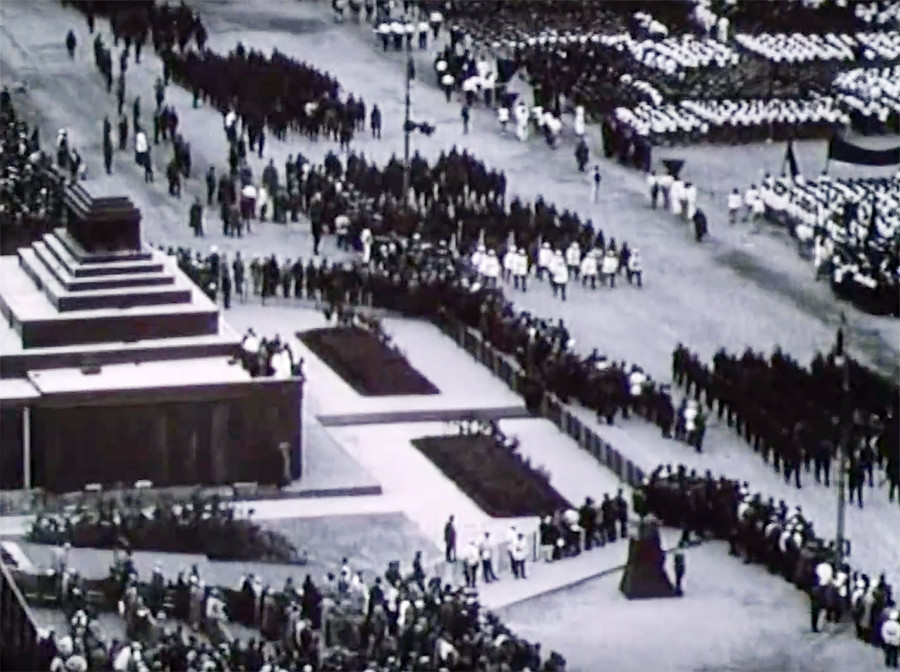

The first all-Union Spartakiade was planned for the same year as the ninth Olympic Games in Amsterdam. Moreover, the Soviet games started the same day the Olympics closed – on Aug. 12. This was no coincidence – the world would compare the two games so the Soviets were determined to make theirs shine.

612 sportsmen from 17 foreign countries arrived in Moscow, most of them from Germany and Finland. All were members of workers’ sport societies, since the Soviet Union contrasted their “proletarian” event to the “bourgeois” Olympics.

The Soviet 1928 Spartakiade trumped its competitor in the numbers of sports (21 - 14) and participants (7,125 - 2,883).

Before it was dissolved in 1937, Sportintern organized several more Spartakiades in cities including Oslo, Berlin, and Antwerp.

In 1952 when the Soviet Union started to regularly participate in the Olympic Games, the role of Spartakiades completely changed. They were no longer an alternative to the Olympics, instead the event became an important practise stage phase and tested Soviet sportsmen before major international competitions.

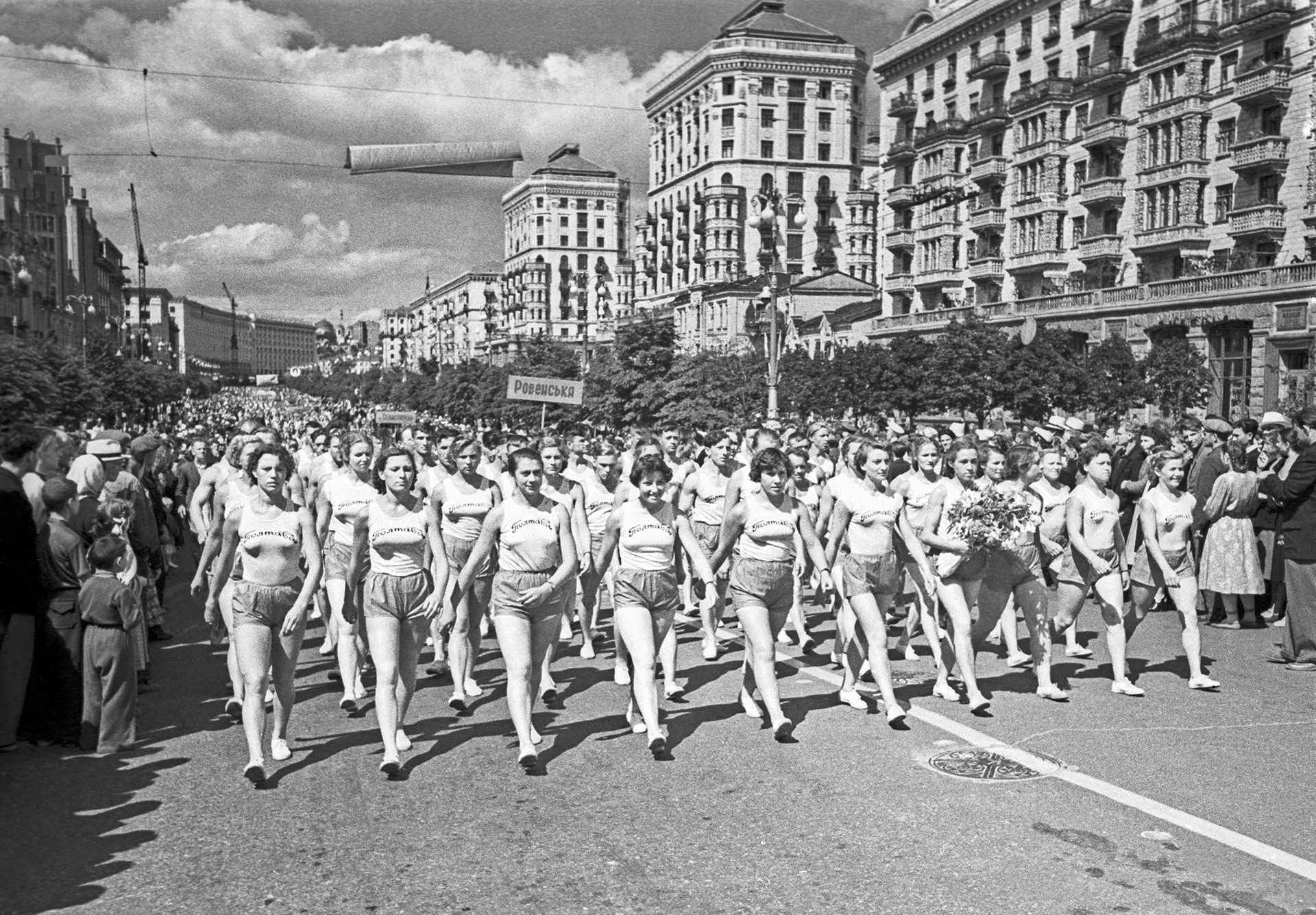

The first Spartakiade of this type was held in 1956 and became known as the Spartakiade of Peoples of the USSR. Since there was no more need to rival the Olympics and invite foreign sportsmen, these Spartakiades were completely internal competitions featuring domestic sportsmen only.

In 1962, the first Winter Spartakiade of Peoples of the USSR was held. The event was also held every four years, but it did not coincide with the Olympics.

Almost all athletes from the Soviet Union competed at Spartakiades of Peoples of the USSR. The 1967 competition was devoted to the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution and set a record for number of participants – over 85 million including amateur athletes of different ages and professions - from students to teachers, medics to engineers. They all tried to qualify for the main event, where only thousands participated.

During the 1979 Spartakiade the Soviet Union decided to break tradition and invited foreign athletes. The next year Moscow hosted the Olympic Games, so it was basically a rehearsal.

For years the Spartakiades were one of the most popular sporting events in the Soviet Union and an incubator for future Olympic champions, but in 1991 they ceased to exist along with the downfall of the country.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox