8 mind-blowing facts about Harbin, the Chinese city built by Russians

Go back 150 years and the area along the Songhua River was but a collection of rural settlements. Fast-forward to modern-day Harbin, and you’ll find 12 million Chinese citizens going about their lives amidst an architectural backdrop of Tsarist grandeur.

The reason? Harbin is a city of perpetual re-invention and chaos. Now China’s 8th largest urban area, current residents work on the skeleton of a village built in the early 20th century by enterprising Russians in search of prosperity, and who tried to recreate their homeland.

Today, the city is practically devoid of Russians (except a few expats), but Harbin’s history once was home to some of the Motherland’s brightest entrepreneurs, most vulnerable refugees, and its most scheming extremists. Here’s the lowdown on the city’s rich heritage.

1. The original ‘Dubai’

The first thing in Harbin was the train station. As the first Trans-Siberian trains made successful eastward voyages in 1896, Tsar Nicholas II’s ambitious Finance Minister, Count Sergei Witte, wasted no time in subsidizing another route: the Chinese Eastern Railway. Central to his grand plan was the newly-formed city of Harbin, which he hoped would link Baikal with Vladivostok, and then have southern routes through China.

After officially acquiring town status in 1898, the area quickly became northeast China’s most buzzing metropolis, and by 1917 it was home to over 100,000 people (around 40,000 of whom were Russian). As very few had been born in the city, Harbin was an expat paradise.

2. Some places still look Russian

Count Witte was keen to make anyone looking at the Harbin skyline know who was boss. The result?

St. Sophia Orthodox Cathedral (opened 1907)

Legion Media

Volga Manor

Legion Media

The European-style High St. in Daoli

Imagebroker/Global Look Press

On the right: Lungmen Grand Hotel (opened in 1901)

Legion Media3. Jewish haven

Long before the Jewish Autonomous Oblast existed, many of Russia’s Jews flocked eastwards to Harbin to escape persecution and start new lives. Since Alexander III and (to a lesser extent) Nicholas II were under the influence of their ultra-conservative childhood tutor, Konstantin Pobedonostsev, the prospect of deportations, education quotas, disenfranchisement, and even pogroms made an eastward move more tempting to Jews.

By 1913, it is estimated that around 5,000 Russian Jews lived in Harbin, with this number rising to around 20,000 by 1920.

Of Harbin’s Jewish legacy only two synagogues remain: one built in 1909; another in 1921; and also a large Jewish cemetery.

Jewish cemetery in Harbin

Jewbask/Wikipedia4. One of the largest White émigré communities

Although most White émigrés fled to Paris, Berlin and Prague, Harbin’s role in welcoming those persecuted by the Bolsheviks is often overlooked by historians.

In a way, it makes perfect sense: starting in 1917 Harbin welcomed pro-Tsarist traders and bureaucrats. With White factions clearly taking note of this, the city’s Russian population skyrocketed from 40,000 to around 120,000 over the course of the Civil War.

Although these White émigrés were mostly left stateless after 1922, their community briefly thrived in Harbin through the establishment of a Russian educational system and Russian-language media.

5. Home of the Russian Fascist Party

In the 1930s, many in Harbin’s Russian community embraced fascism, mostly as an attempt to form an anti-Bolshevik Asian front with Emperor Hirohito’s Japan.

The Russian Fascist Party’s most successful period was under the leadership of Konstantin Rodzaevsky, who claimed to have 20,000 members. Gladly agreeing to an alliance with Imperial Japan, Rodzaevsky’s platform called for liquidation of the Jews, re-establishing the influence of the Orthodox Church, and building a corporatist economic system along Italian lines.

As a result of the RFP’s increasing power, as well as a lack of protection from the Japanese government following its annexation of Manchuria in 1931, the city’s Jewish population fell from 13,000 in 1931 to 5,000 by 1935. But things were about to become far more gruesome.

6. The “Japanese Auschwitz”

The ruins of Unit 731

Xinhua/Global Look PressWhile officially labelled an “epidemic prevention and water supply unit,” and located just 24 km south of Harbin, Unit 731 in fact was responsible for some of the most brutal war crimes ever committed.

Established in 1935 by the Japanese military, Unit 731 ran a facility for live human experimentation that even horror movies couldn’t imagine. Only in 1984 was it revealed that the Japanese subjected prisoners to live dissections, frostbite, starvation, as well as injecting them with the plague.

Russians in Harbin were also targeted by the Japanese, and it's estimated that around 30 percent of the 3,000-12,000 victims of Unit 731 were Russian. Most set a 5 p.m. curfew for their children to prevent them being taken by Japanese police.

7. Stalin wiped out the remaining Russian population

Following the USSR’s sale of the Chinese Eastern Railway to Japan in 1935, as well as due to the random disappearance of people from the streets (taken by Unit 731), most Harbin Russians naturally wanted to leave.

By the late 1930s the number of local Russians had fallen to around 30,000. Those who had chosen Soviet citizenship, and who had their property confiscated by the Japanese, chose to return to the USSR. Ironically, over 48,000 of them were arrested as “Japanese spies” during the Great Purge of 1936-38.

When the Soviet army took the city in August 1945, many remaining residents met a similar fate: those deemed to have had any previous cooperation with the White Army, the Japanese, or the Russian Fascist Party were immediately rounded up and sent to the GULAG.

Most remaining Russians in Harbin were repatriated to the Soviet Union, and in the Chinese census of 1964 just 450 Russians were counted in the city. The final two Harbin Russians died in the 1980s.

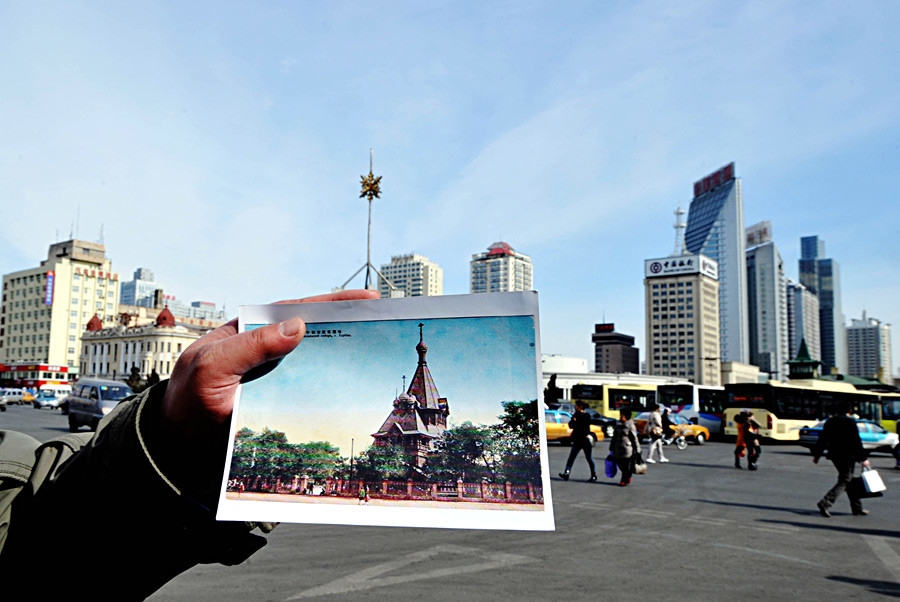

8. Locals try to save the city’s Russian heritage

A visitor of the ethnographic project "A Russian Village on Sun Island Near Harbin."

Evgeny Yepanchintsev/SputnikHarbin’s historic Russian architecture is losing out to modern Chinese construction, but locals are fighting back. When there was talk about destroying the city’s iconic 1920s Qihong Bridge, a local movement fought to have it classified as “an immovable cultural relic.”

When the Harbin Ice Festival comes to the city every year, the organizers make sure that an Ice Kremlin is built.

One of the city’s historic restaurants, Lucia, has also preserved its unique Imperial Russian interior.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox