How did Africans prosper in Tsarist Russia?

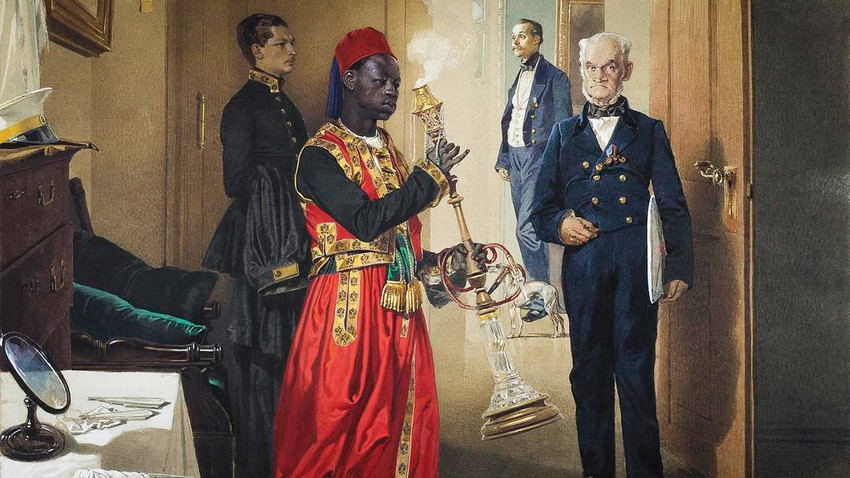

Painting of Emperor's palace with an arap serving there.

Mihály Zichy/Hermitage Museum“They looked at the young Negro as if he was a miracle, surrounded him, showering him with greetings and questions; but this kind of curiosity annoyed his self-esteem… He felt like some a kind of rare animal,” wrote Alexander Pushkin, the famous 19th-century poet, in his historical novel, The Moor of Peter the Great, which described the life of an African man, Ibrahim, at the tsar’s court.

Pushkin had personal reasons to write this novel. Ibrahim was a historical figure, a slave from Africa who later thrived in Russia, became a nobleman and helped establish a dynasty. Even more, Pushkin was his great-grandson.

Making it big in Russia

Abram Hannibal's monument in the Petrovskoye village, Pskov Region, Russia.

Ludushka/WikipediaWhatever his true homeland might be, it’s almost certain that the Turks kidnapped him, and through the slave trade he ended up in the Russian court. Peter the Great treated Ibrahim well, and not only did he grant him freedom, but he baptized him as Abram Petrovich Hannibal, (after the famous North African commander of Ancient Carthage, a surname Ibrahim chose himself)

(Allegedly) portrait of young Abram Hannibal.

Legion Media“The African, or should I say the African-Russian, witnessed and helped to establish diplomatic, scientific and cultural relations between the two great European countries: Russia and France,” Gnammankou said in an interview with TASS.

Hannibal also had his share of hardships. After Peter the Great died in 1725, his African favorite fell out of grace with Russia’s new ruler and was exiled to Siberia. When Peter’s daughter, Elizabeth, ascended the throne, Hannibal returned to his estate and led a long life, having 11 children. Among them was Pushkin’s grandfather, Osip Hannibal, and so the poet always remembered his African heritage.

Black courtiers

Peter the Great's portrait with a black valet,

Baron Gustav von MardefeldHannibal’s story is quite unusual, but not unique. In the 18th and 19th centuries, many people of color served at the Russian court as araps. Don’t confuse them with Arabs. An arap, according to Vladimir Dal’s 1863 dictionary, meant “a black-skinned person from the hot countries, mainly Africa.” The second meaning was “a porter, a gatekeeper,” and that’s what the araps did

Sophie Buxhoeveden, a maid of honor for Empress Alexandra (Nicholas II’s wife), recalled: “Black servants, dressed in Oriental clothes, gave a special, exotic taste to everything in the palace.” Their presence symbolized how large and powerful the empire was, embracing the whole world with its influence.

Sounds racist? Perhaps, but remember that such practice was common at the courts of most European monarchs of that time, and it paid very well.

“The araps were among the few at the Tsar’s palace who had a salary and it was quite large,” historian Igor Zimin explains in his book, Court of the Russian Emperors. Most servants worked for room and board.

Russia or bust

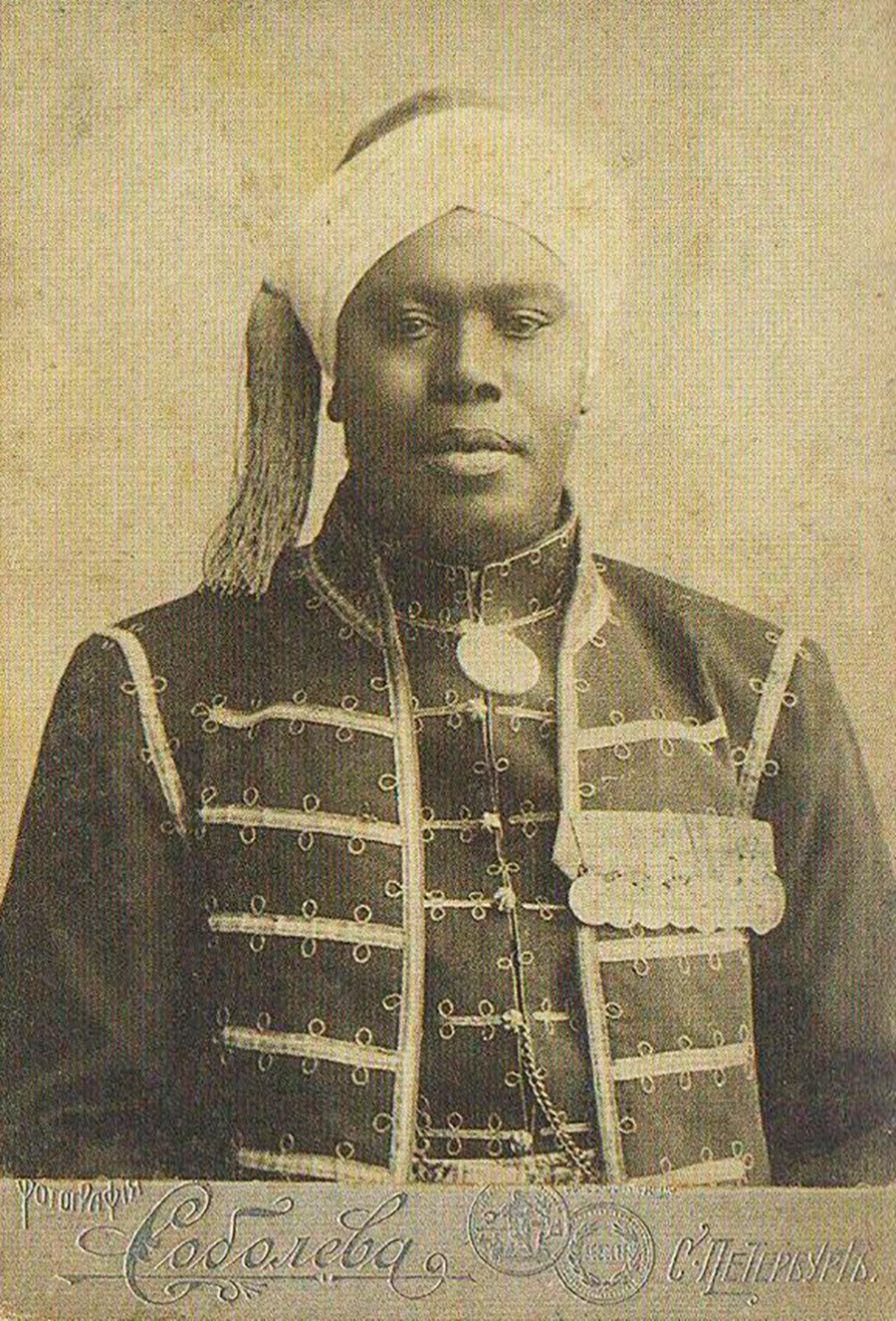

George Maria, an arap from Cape-Verde, who settled in Russia.

Public domain“The first American arap at the Russian court was an ex-valet of the U.S. envoy to St. Petersburg, who got his new job in 1810. It seems that news of this fine job spread fast in American ports, and many black adventurers rushed to Russia, usually as sailors on those few ships heading to St. Petersburg,” Zimin writes.

Job competition was intense, however, and during the reign of Nicholas I (1825 – 1855) the number of court araps was limited to eight. Previous empresses with a penchant for exoticism had had dozens of black servants. The blacker and taller the potential employee, the better, according to Zimin. Also, anyone wanting to serve at the court was obliged to be baptized into Christianity (not necessarily Orthodoxy).

It wasn’t only Americans who became araps. Nina Tarasova, who works at the State Hermitage Museum, tells the story of George Maria from Cape Verde (a Portuguese colony) who served at the tsarist court for many years and stayed in Russia long after Nicholas II’s abdication.

“Both sons fought in the Great Patriotic War, one died and the other made it to Victory Day,” said Tarasova.

As you can see, some araps laid deep roots in Russia. In general, however, their best days ended with the fall of the empire in 1917. During the Soviet period, a new type of African, as well as African-Americans, found opportunity in the county – as students, engineers, and socialist leaders. But that’s a whole other story.

An outstanding example of the African-Americans who made it to Russia was Robert Robinson, who lived in the USSR for 44 years (though wasn't always happy about it). Read his story now – you won't regret it.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox