How American scientists saved a Soviet child at the start of the Cold War

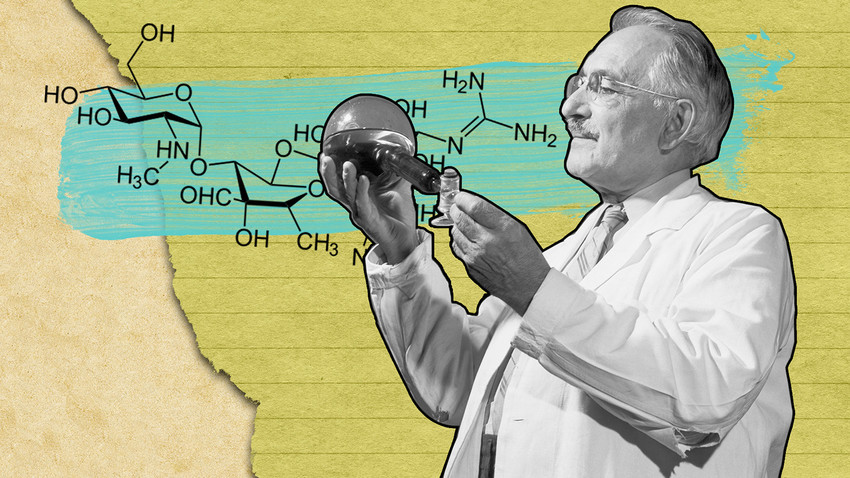

Selman Waksman, the inventor of streptomycin, published Irina’s photo in his first book about his breakthrough. While she was not the biochemist’s acquaintance or a relative, Waksman responded to a cry for help from the Soviet Union to save Irina’s life. Since the Soviet government had more pressing problems at the time, her parents had to act on their own.

A gram of

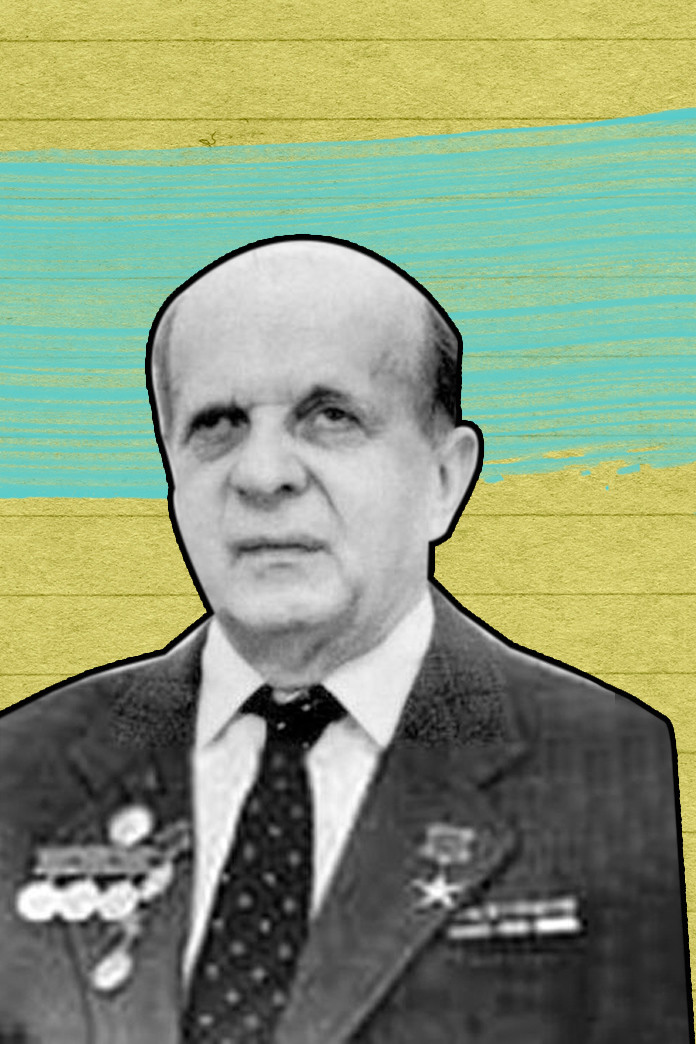

Veniamin Tsukerman, Irina's father

Archive photoLike many Soviet scientists, Tsukerman listened to forbidden foreign radio stations, and on the day his daughter was diagnosed he heard via a London radio broadcast that a new drug called streptomycin had been successfully developed to treat the disease. Through his connections, Tsukerman learned that streptomycin was already available in Moscow, but there was only a gram, and nobody knew the proper dosage.

Tsukerman’s friend, Israel Galynker, suggested a wild idea – to call the U.S., find the practitioners that already tested the drug and consult them on the dosage. At that time, any attempt to contact a “hostile Imperialist state” often ended in charges of espionage, but Tsukerman and Galynker decided to act immediately despite the danger. The call was placed not from an institution, but from the private flat of the Tsukerman family, where it was harder to trace. All they knew was the name of the hospital – the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

Smuggling for

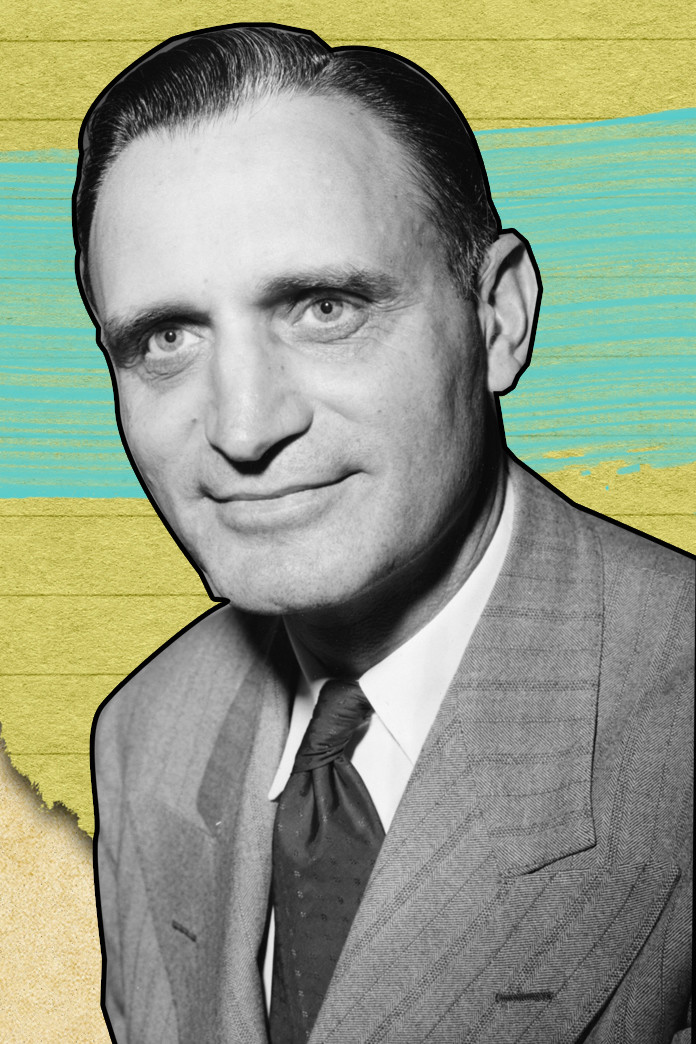

Dr. Corwin Hinshaw

Smithsonian Institution ArchivesIn the U.S, in the 1940s, streptomycin was considered a “strategic medicine,” and Congress controlled its distribution and export. There was no legal way of selling the drug to the hostile USSR. Luckily, Lina Shtern, a Swiss-Soviet biochemist, managed to convince her brother in the U.S. to send her tiny packs of the drug. Everybody who could in the Soviet scientific world was eager to help little Irina Tsukerman. She was by far not the only child ill with the killer disease, and hundreds of families hoped for salvation

Selman Waksman

Library of CongressInadvertently helping the deaf

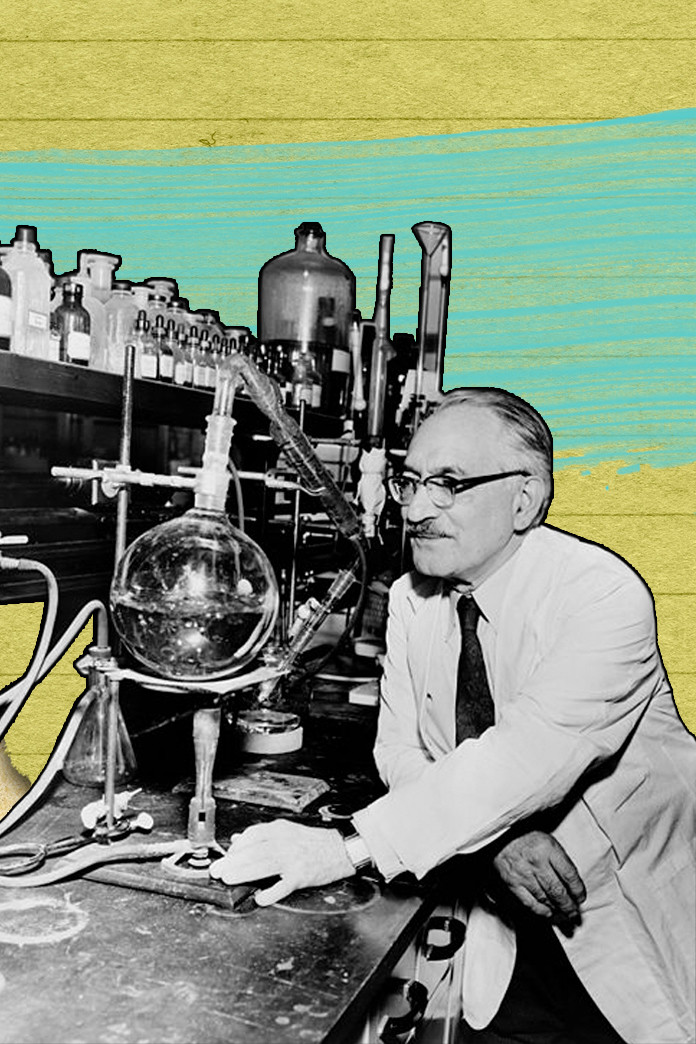

Veniamin Tsukerman, irina Tsukerman, Israel Galynker, Moscow, 1956

Boris Altschuler/UFNGalynker’s phone call to the U.S. didn’t go unnoticed. All Soviet physicists at the time were under close surveillance. Galynker was accused of espionage for contacting

After she was healed, Irina completely lost her hearing. Still, growing up in a scientific family, she graduated from the Moscow State Technical University and spent her life studying methods of communication for deaf people, as well as inventing and testing hearing devices, and working on the adaptation of Morse code for the deaf. She died this October in the very house where she and her parents had lived their entire lives.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox