Take me out to the ball game, comrade: The untold story of the origins of Soviet baseball

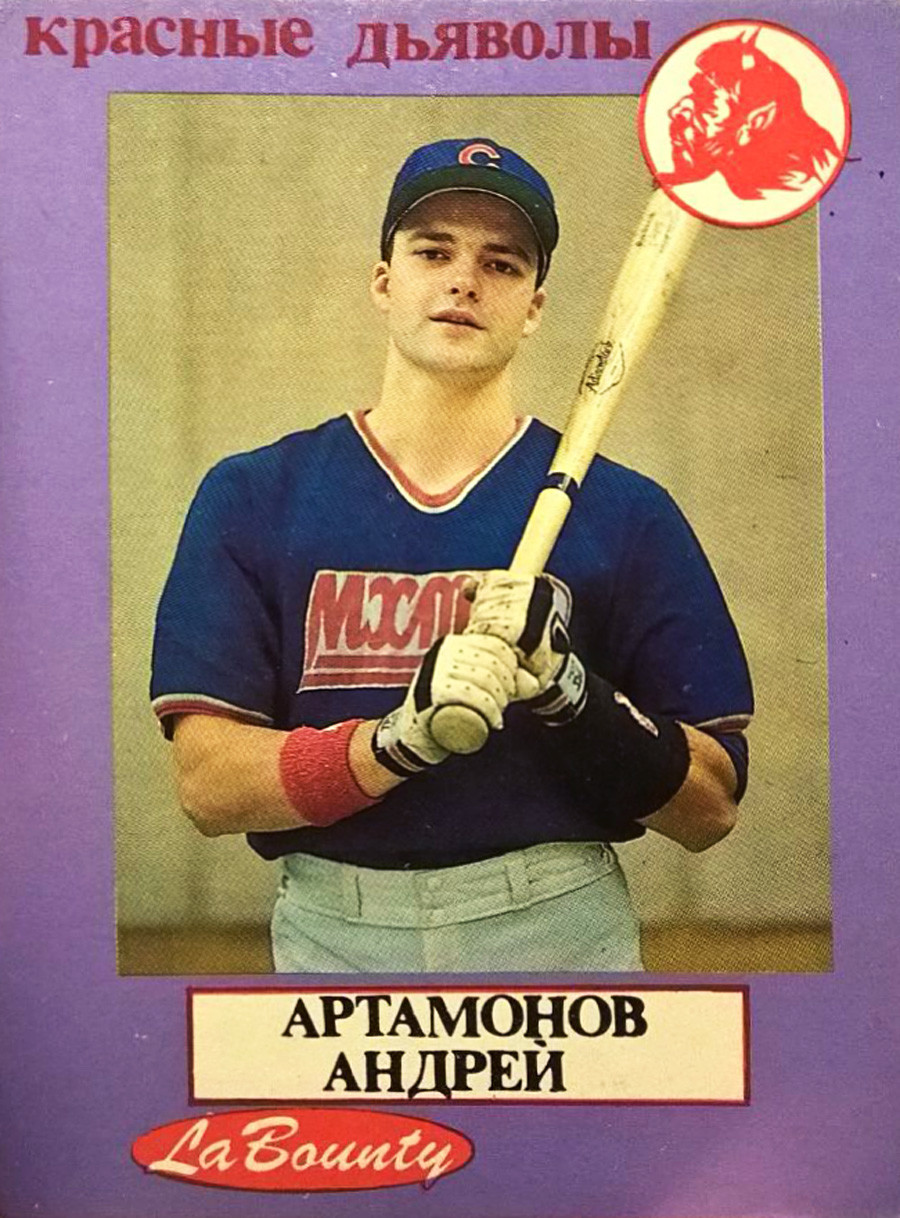

When RusStar won the 2018 championship in Russia’s Amateur Baseball League, it was a particularly happy moment for the coach, Andrey Artamonov – a flashback to his youth.

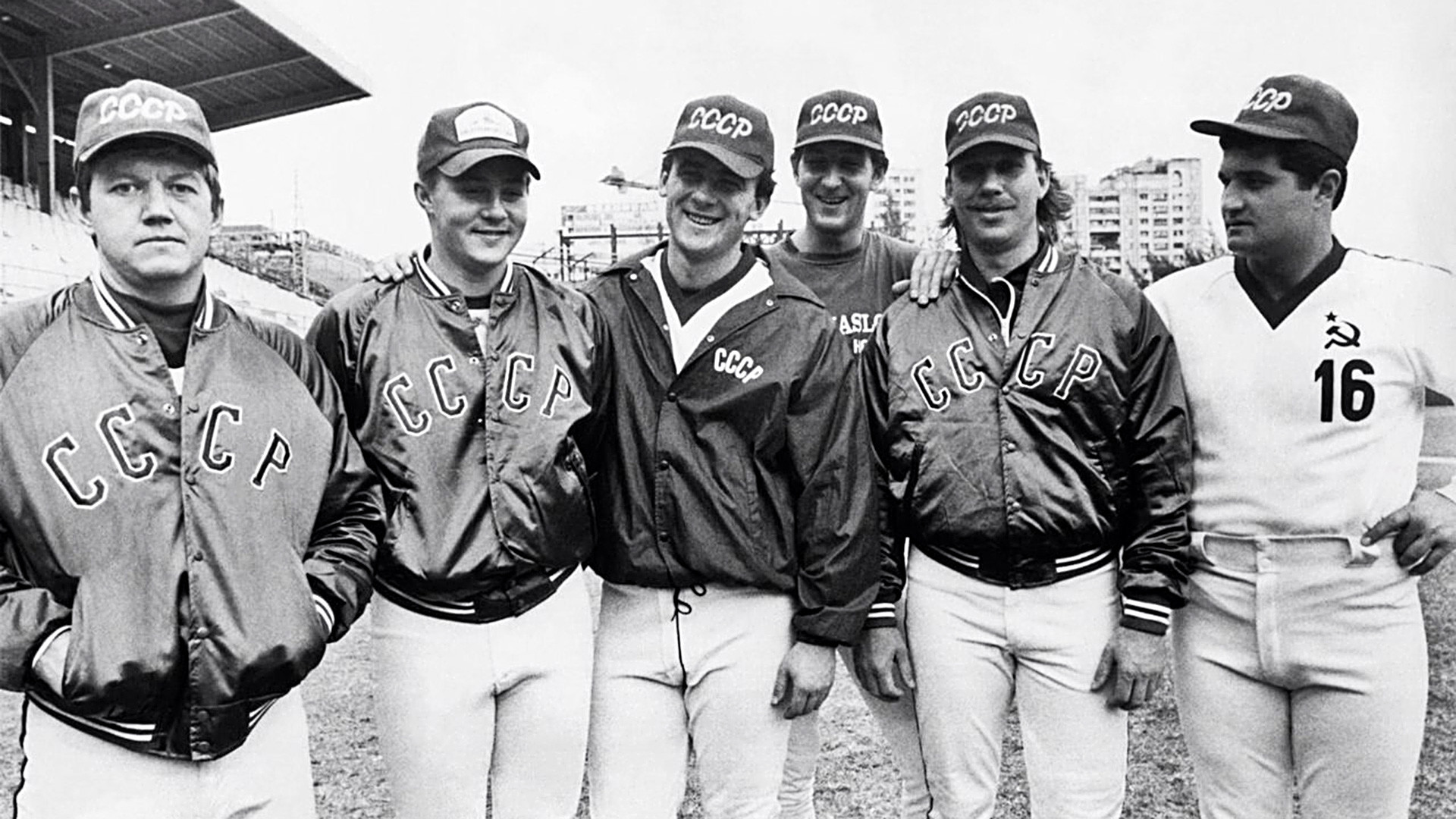

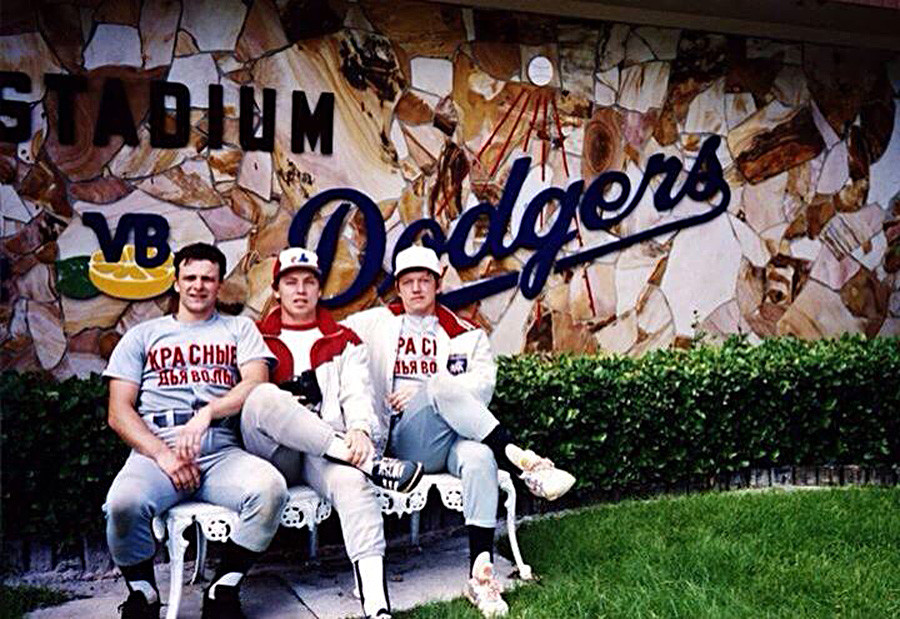

In the late 1980s, the Soviet government drafted him and other young athletes from various backgrounds to form a new team that would have to learn how to play a sport they had never heard of – baseball. Their goal: to beat the Americans at their own game.

The final nail in capitalism’s coffin?

Artamonov, now a 50-year-old baseball coach, gave up hockey to make an unlikely career in baseball in a country where no one knew anything about the foreign game. His father was a professional hockey player, and he only knew baseball from watching U.S. embassy staff play rare games next to the Burevestnik Stadium in Moscow, where he lived as a child.

The young man would have stuck with the stick and puck, but the Soviet government knew better. In 1986, officials figured the country needed its own baseball team. These were times when Soviet might was proudly demonstrated through various sport competitions. The Soviets had already beat the Canadians in hockey, and crushed the Americans in basketball. It was just the right time for the last nail in the coffin of the capitalist sports industry.

The first Soviet baseball team was quickly formed with men of all backgrounds, from hockey to javelin. The only criteria was their physical fitness. To many players it came as no surprise in 1987 when the team lost its first game ever, with the humiliating score of 22:0 to a team from Nicaragua.

The players’ skills grew fast, however, and the time for challenging the Americans finally came in 1989.

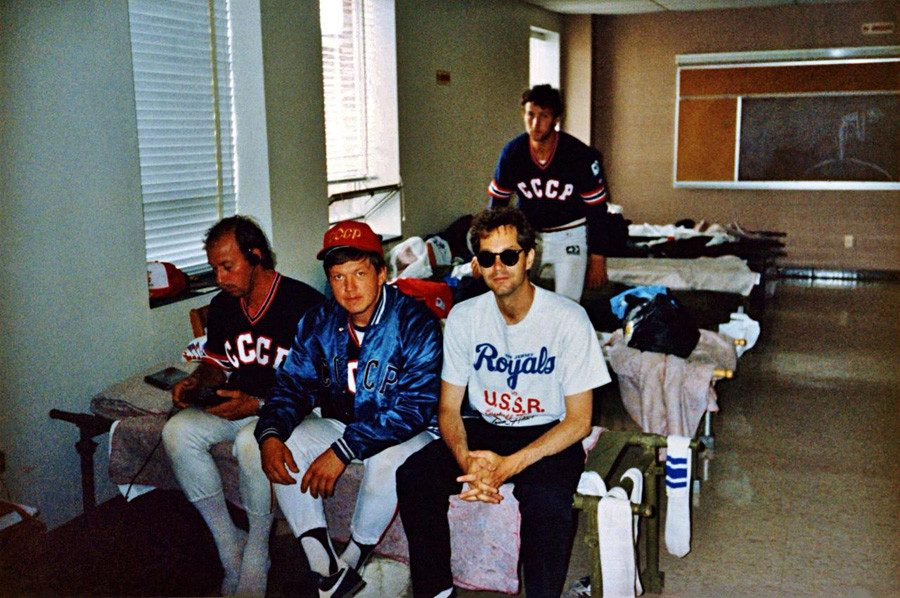

“They summoned us to the Olympic Committee of the USSR, and we received bags with beautiful uniforms branded with 'USSR'. Then they gathered us and began to lecture that in the U.S. we were not supposed to walk the streets alone; and alcohol and even cigarettes were prohibited. Then there was something that alarmed us,” said Artamonov.

Almost beaten by the Komsomol

Every team that went abroad had to have among their players a representative of the Komsomol, the Communist Youth Union. The problem was that the baseball team didn't have such a person.

“We couldn’t care less about politics; we just wanted to play. But to go to the States we had to comply because otherwise they could have cancelled the trip,” said Artamonov.

Caught off balance by this delicate issue, and knowing that the team’s fate might depend on the right answer, the coach pointed at the youngest player on the team.

“Unfortunately, this happened to be the guy who rarely uttered a word at all,” said Artamonov.

“Usually close-mouthed, the player, Ilya Onokchov, stood up and made such an inspiring speech about Soviet ideals in sports that everyone was taken aback. And finally he said ‘And we will win at least one game against the Americans.’”

The entire team was in silent shock: they all knew that only sheer luck could save the amateurs from a humiliating defeat at the hands of professional baseball players. Nobody on the team thought they could possibly live up to such a bold promise made to a Soviet party official.

Accompanied by a KGB officer (this was mandatory for all Soviet sports teams going abroad), the Soviet players arrived in Florida.

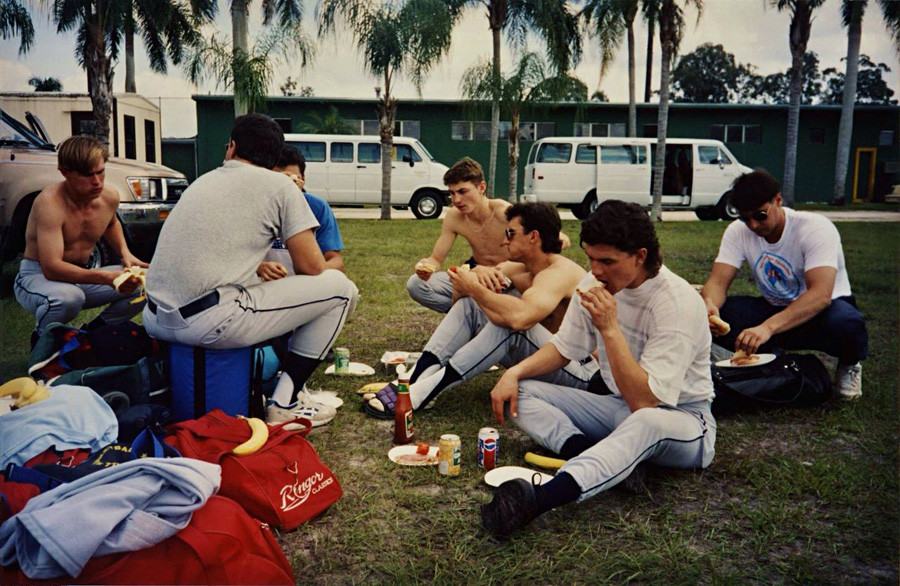

“To our surprise, we won two games out of six,” said Artamonov. “We delivered on our promise, and even exceeded it.”

The successful American tour put Soviet baseball on the right track. By 1991, the “red” team moved forward, playing against teams from Italy, France, Switzerland, Great Britain, Belgium and more.

White House reception

President Ronald Reagan had just taken off from the White House on board Marine One when he was told that the Soviet baseball players had just arrived at the president’s residence as part of a guided tour.

“Marine One landed right back on the White House lawn, and Reagan came out to meet us and shook everyone’s hand,” said Artamonov.

Today, Artamonov brushes off such attention as nothing important. “We shook hands [with Reagan]; we also shook hands with George W. Bush,” he said, adding that he still has a postcard personally signed by the latter.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, the Americans lost interest in the “red” players. “Back then, when Americans knew that the Soviet team was coming they did not have much of a understanding of what to expect: bears or people. They wanted to touch us, to see us. Everything has changed,” said Artamonov, sadness visible in his eyes.

Although some Russian players have moved and now play with U.S. teams, Artamonov has stayed in Moscow, and isn't sure if his Florida residency and driving license, issued nearly 30 years ago, has already expired.

Today, he finds solace as a coach who has led the RusStar club to victory in Russia’s Amateur Baseball League. He runs an indoor batting cage at the Multisport Center in Moscow’s Luzhniki complex, where he trains amateurs and professional baseball players with a pitching machine and balls delivered straight from Florida.

"I always admired the amateur league. Professionals play baseball as a job, they prioritize money. Amateur baseball is pure love for the sport. The game for the sake of the game,” said the coach, adding with a sigh, “Am I old and sentimental?”

Click here to read about the rise and decline of Soviet hockey.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox