3 U.S. citizens who did time in Soviet prisons

1. Lovett Fort-Whiteman (1894-1939)

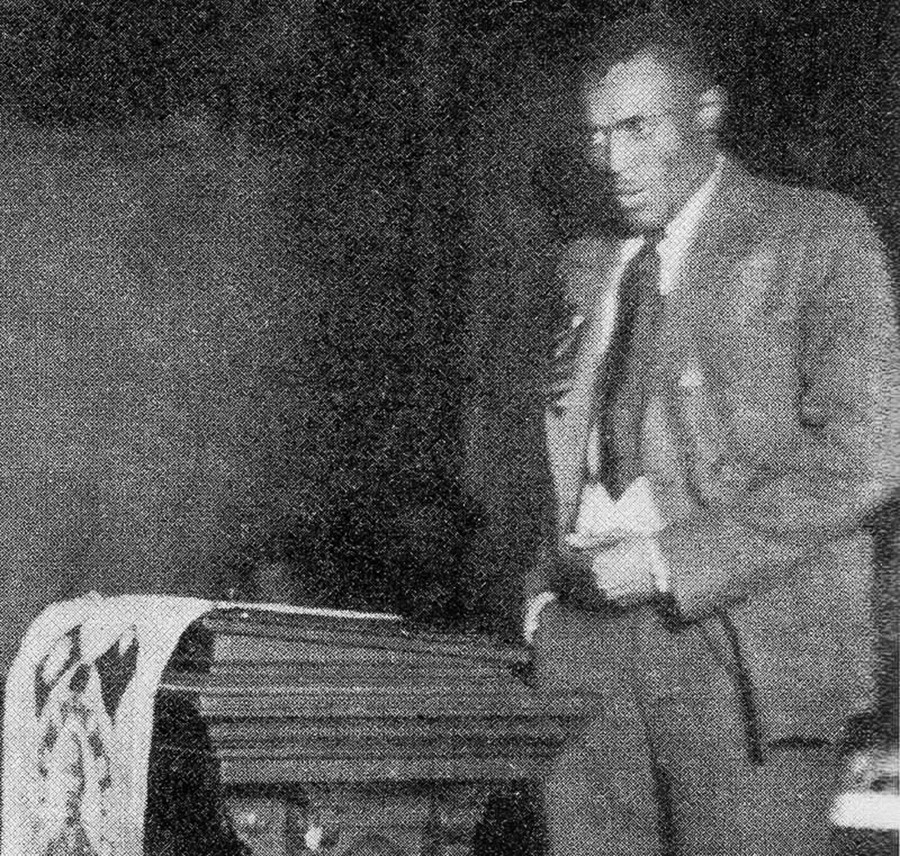

Fort-Whiteman (1894-1939), American political activist, speaking at the opening session of the founding convention of the American Negro Labor Congress.

Public domainFort-Whiteman, the first American-born black communist, is also the only known African American to have died in a Soviet labor camp. It all started so well. Born in Dallas, Texas, to a family of a former slave, Fort-Whiteman championed civil rights for African Americans, joining the Communist Labor Party of the U.S. in 1919.

The Soviets, keen on internationalism, welcomed a black communist. In the 1920s, Fort-Whiteman attended a training school in the Soviet Union and became a member of the Comintern, international Communist organization. Traveling from the U.S. to the USSR and back, the activist founded the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC), the official organization for black communists in the U.S.

“He was a talented journalist, a very good boxer, a kind of a Renaissance man who knew four foreign languages and dreamed of learning all his life,” historian Sergey Zhuravlev says. From 1928, Fort-Whiteman lived in Moscow, working as a teacher at an Anglo-American school; he even married a Russian woman

Soon enough, Lovette Fort-Whiteman found himself starving in Kolyma.

Public domain“There in Kolyma no one mourned him, no one knew he was the first African American communist. No one knew of his eagerness, his recklessness, his abiding faith in poor working people,” writes Professor Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore in her book Defying Dixie: The Radical Roots of Civil Rights.

2. Thomas Sgovio (1916-1997)

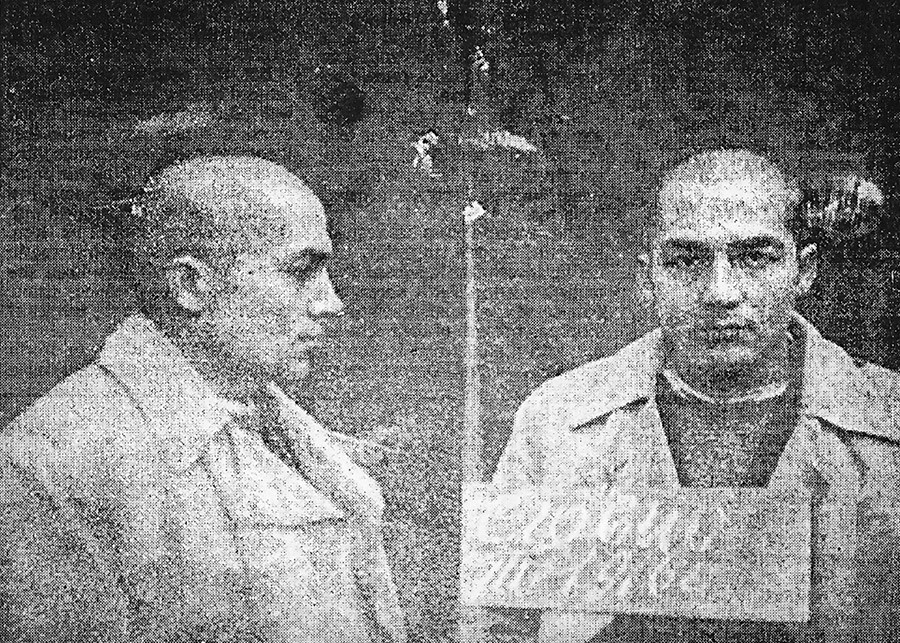

Thomas Sgovio arrested in USSR on March 21, 1938.

USSR NKVDThe 1930s were a hard time for America’s farmers and working class due to the Great Depression, so it comes as no surprise that many embraced leftists ideas and some moved to the USSR. That’s what happened to Thomas Sgovio, a youngster who followed his father Joseph, an Italian-American communist deported from the U.S. in 1935. Thomas Sgovio was 19 - and would spend another 25 years in the USSR.

“When Thomas moved to the USSR, he thought he was entering the land of freedom. At first, it felt like that. He enjoyed his life, being young, going to dance clubs for foreign workers here in Moscow, meeting girls…” Sergey Zhuravlev explains.

The honeymoon ended three years later when Soviet authorities arrested Joseph Sgovio and Thomas visited the U.S. embassy in Moscow, trying to restore his American passport. Immediately after he left the building, two men arrested him. His trial was swift: as “a socially dangerous element”, the young American was sentenced to hard labor

Nevertheless, almost two decades inside the Gulag were hardly a breeze for the young man. “When he returned from the camps in 1954, he recalled how he lay down on white sheets and for a month couldn't get used to the absence of lice,” Svetlana Fadeeva of Memorial International Society says. In 1960, Sgovio was finally allowed to leave the USSR. He returned to the U.S. where he wrote a book Dear America! Why I Turned Against Communism describing his hard times in the Soviet camps.

3. Dennis Burn

Three U.S. citizens appear in a Moscow court, charged with drug smuggling, Aug. 24, 1976. From left: Dennis Burn, Paul Brawer, and Gerald R. Amster.

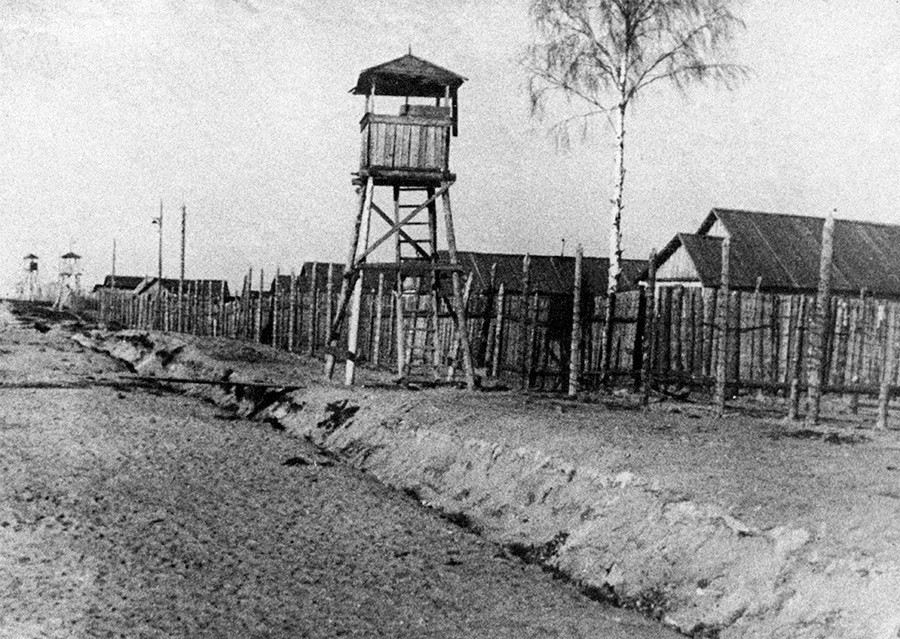

AP"Ever been to Laredo? On the Texas-Mexican border? Dilapidated little structures, horses and wagons... it was like the world just ended there." That’s how Dennis Burn, an American citizen imprisoned in the USSR, described a camp in Mordovia (about 400 miles east of Moscow) where he spent seven years. It may be the only time ever that someone compared Mordovia to Texas.

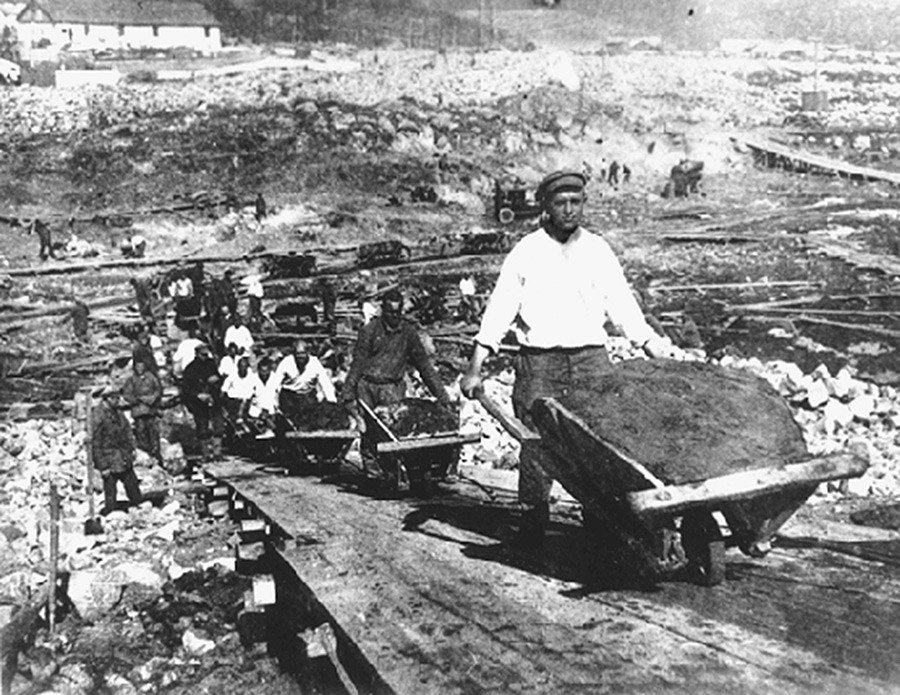

Unlike Fort-Whiteman or Sgovio, Dennis Burn wasn’t a communist fascinated by the USSR’s opportunities. His story is more like a Quentin Tarantino movie about low-life petty criminals. A 26-year-old from Queens, New York City, he was invited to join an international drug trafficking gang in 1976 and took up the offer just for the hell of it.

He and two other Americans (Paul Brawer and Gerald Amster) were carrying 62 pounds (28kg) of heroin in three false-bottomed suitcases from Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to Paris, France, with a transit stop in Moscow. After the unexpected check, Burn didn’t make it through, and all three couriers were arrested and charged with smuggling drugs.

Nevertheless, the former drug courier was stubborn enough to participate in hunger and working strikes - in interviews, both he and Amster agree that that was the reason he wasn’t released earlier. After stepping out of the camp and leaving the USSR immediately in 1983, he said: “I've learned to appreciate things, little things.” He has since disappeared into the obscurity from whence he came.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox