What happened to disabled WWII vets in the USSR?

“Hundreds of thousands of disabled people, without arms or legs, forlorn and begging at train stations, in the streets and elsewhere. The victorious Soviet people eyed them warily: orders and medals shining on their chests, and they’re begging for change near grocery stores! That’s unacceptable! Get rid of them by any means possible – send them to the former monasteries, to the islands… In a few months’ time, the country cleared its streets from this ‘shame’. That’s how these almshouses came to exist…” That’s how Evgeniy Kuznetsov, a historian of art from Leningrad, described the ‘evacuation’ of disabled WWII vets from the Russian mainland.

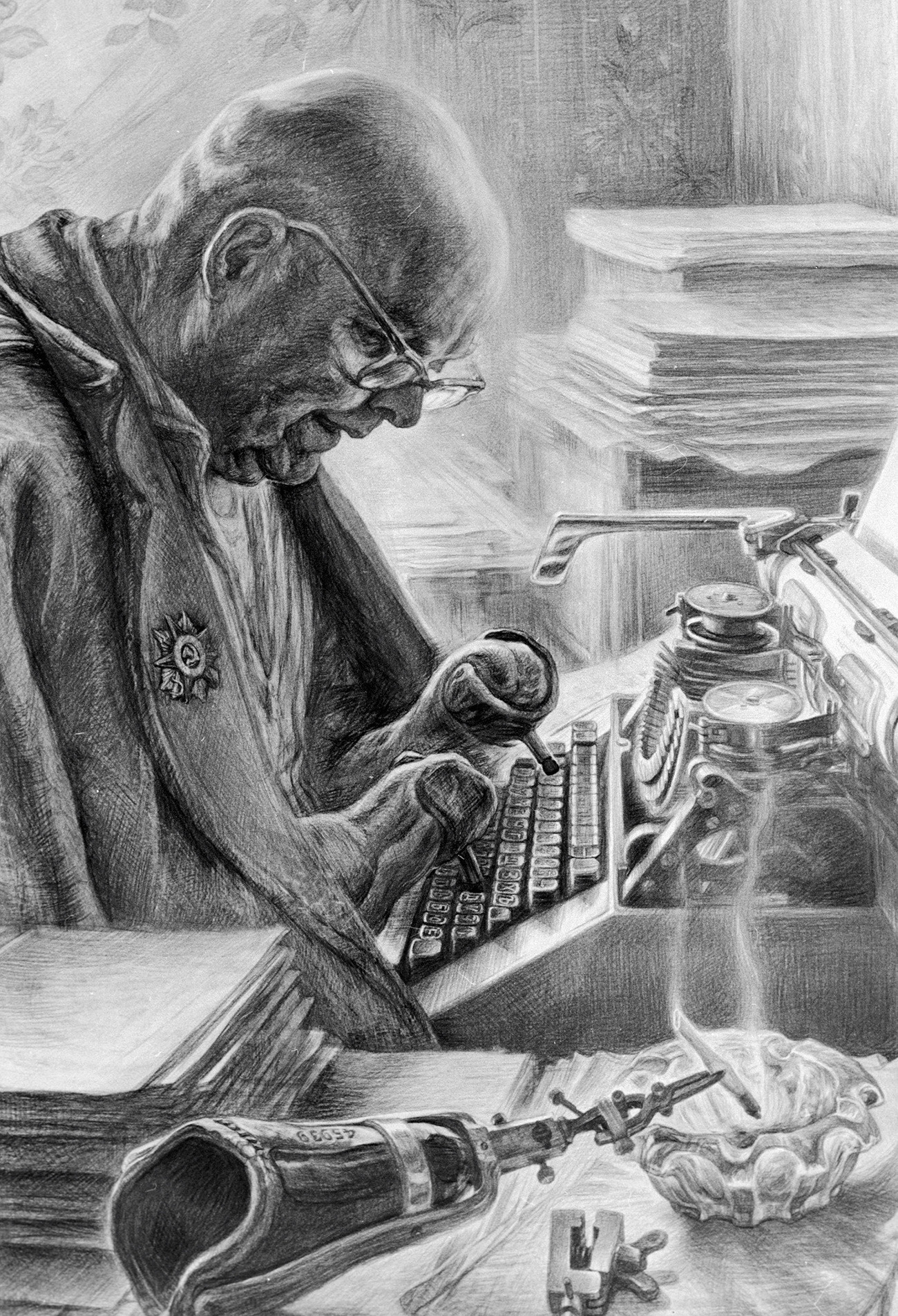

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. Boris Mileev from Moscow typing his memoirs with his prosthetic hands.

For 40 years, Kuznetsov had been working as a guide in Valaam monastery, that became the main sanatorium for disabled vets. His emotional and accusatory recollections, however, don’t do justice to the truth. In reality, the country treated its disabled much better.

The 'samovar people'

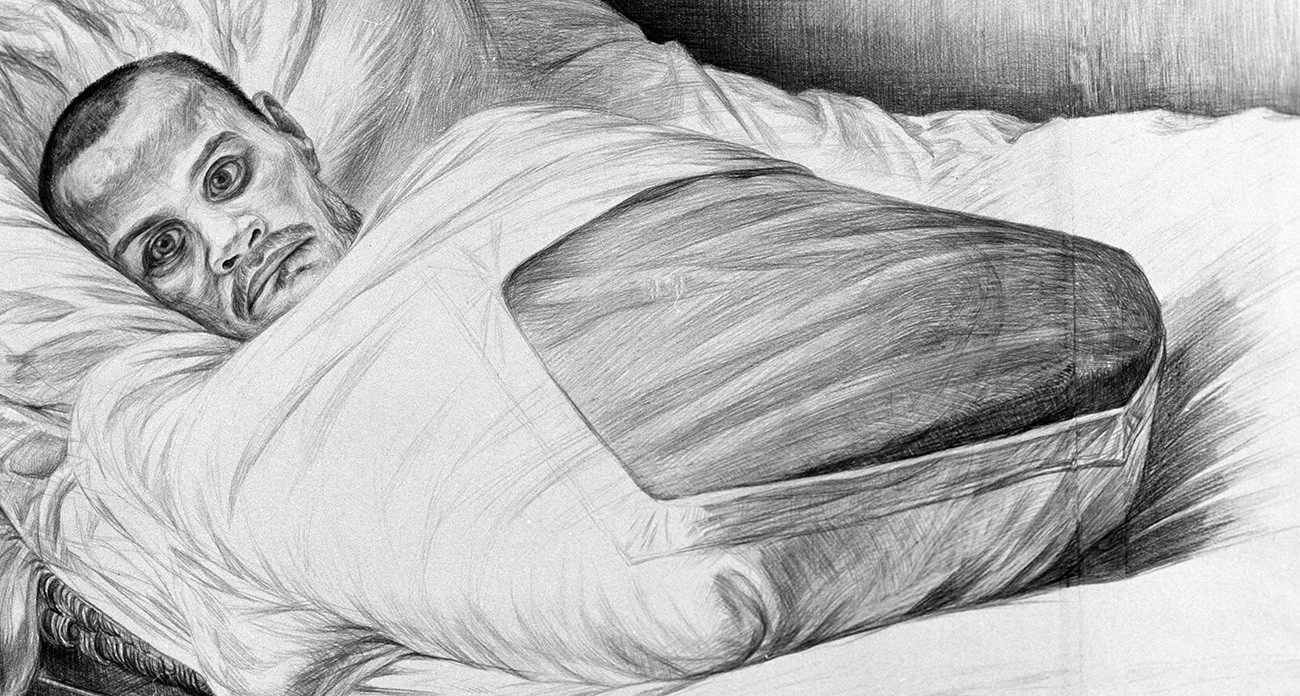

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. An unknown person who lost limbs, hearing, and the ability to talk.

The figures say that during WWII, the USSR had some 4 million people demobilized because of wounds and diseases, including about 2,5 million disabled people; among them, about 450-500 thousand lost limbs. Those who returned home without limbs at all were grimly called “samovar people” because of their resemblance to a samovar (tea boiler). An urban legend has it that after the war, the disabled were evacuated from central cities to the former monasteries in Russia’s North, and it was reportedly done overnight. It’s hard to believe – because it’s fake. We must address other sources.

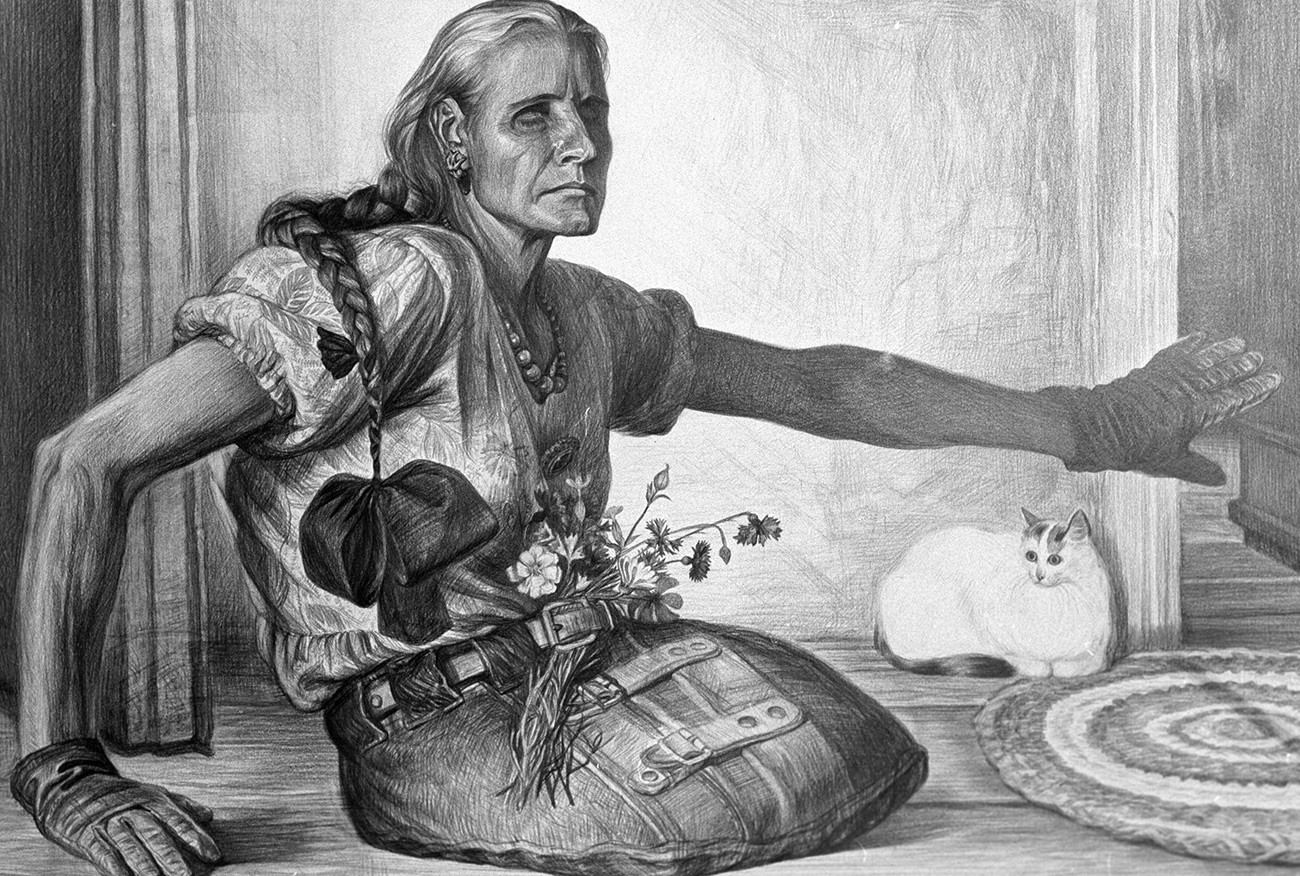

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. A former military radio operator Julia Emanova from Stalingrad, who lost her limbs, hearing, and eyesight.

Eduard Kochergin, a St. Petersburg writer, described the life of one of the war amputees in the former Goritsy monastery, that had been refurbished into a sanatorium for the disabled.

“Soon after his arrival in Goritsy, Vasiliy became famous. From all Northeast of Russia, stumps of war, men and women without legs and arms, were brought. “Samovars”, people called them. Vasiliy, with all his passion and ability for music, had created a “samovars choir” and found a new meaning to life… In summer, twice a day, the women attendants took their ward for some air beyond the monastery walls, placing them in the tall grass on the steep Sheksna river bank...

In the evening, while steamers were going to and from the pier, the “samovars” held a concert. Startled with the mighty and unrestrained sound, the passengers stood on their toes and went to the upper deck of their ships to see where the singing was coming from, but the “stumps” couldn’t be seen among the tall grass…”

Nothing to lose

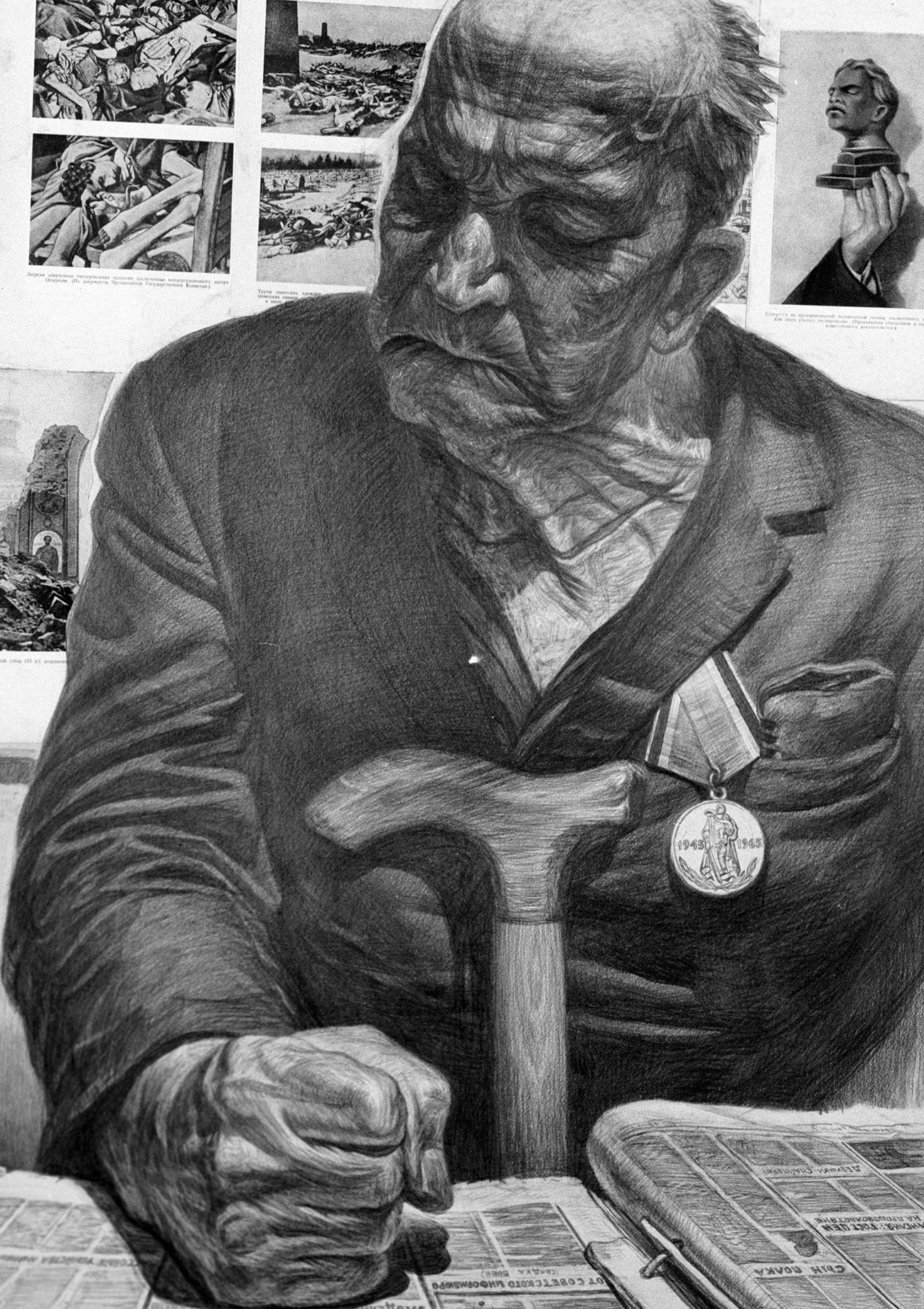

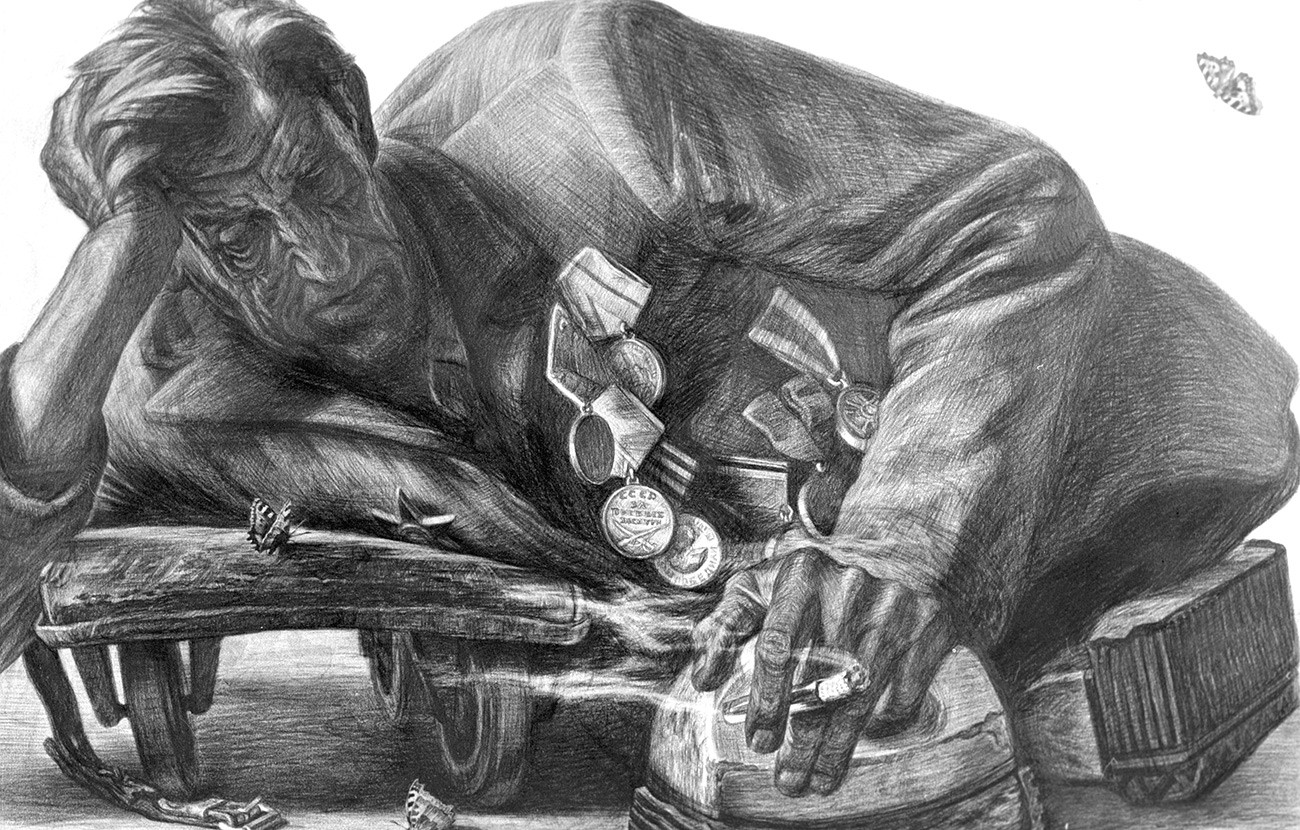

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. Georgiy Zotov from Moscow region during a meltdown as he read wartime papers.

It’s a bold thing to say the Soviets just wanted to hide those people. Many of them had families – but could these families, impoverished and partly destroyed by war, provide for the disabled? On the other hand, the war amputees were indeed fearless – they had nothing more to lose, so they weren’t reluctant to openly criticize the Soviet regime. The KGB reportedly had a special division that monitored the amputees’ activities. That’s why so many documents from the sanatoriums have been preserved in the archives. Thanks to Vitaliy Semenov, the genealogist who found them, we now know that sanatoriums weren’t compulsory and by no means prisons.

A disabled war vet at a victory parade in 1970.

READ MORE: An interview with Vitaliy Semenov in our article “How foreigners search for their Russian ancestors”

The ‘evacuation’ of the disabled began around 1948. The state offered shelter and food to those disabled people who couldn’t find their families (they were either relocated, displaced or died in the war) or to people whose families had deserted them (sadly, there were some). Semenov, however, did find several records about the disabled who managed to get back to their families. In 2012, a student mailed Semenov some memoirs about the disabled she had recorded at the Andoga sanatorium, Nikolskoye, Cherepovets region: “Those unable to walk were taken out for air on sunny days. The disabled were systematically attended to, medically. Daily at 8AM, there were inspections of all patients, a steady supply of medication, three meals a day and an afternoon snack. The disabled loved to work, read books in the library, those who could, went to pick mushrooms and berries. Almost no relatives came to see them, but many disabled started new families with the young women who had lost their husbands in the war. The sanatorium existed until 1974.”

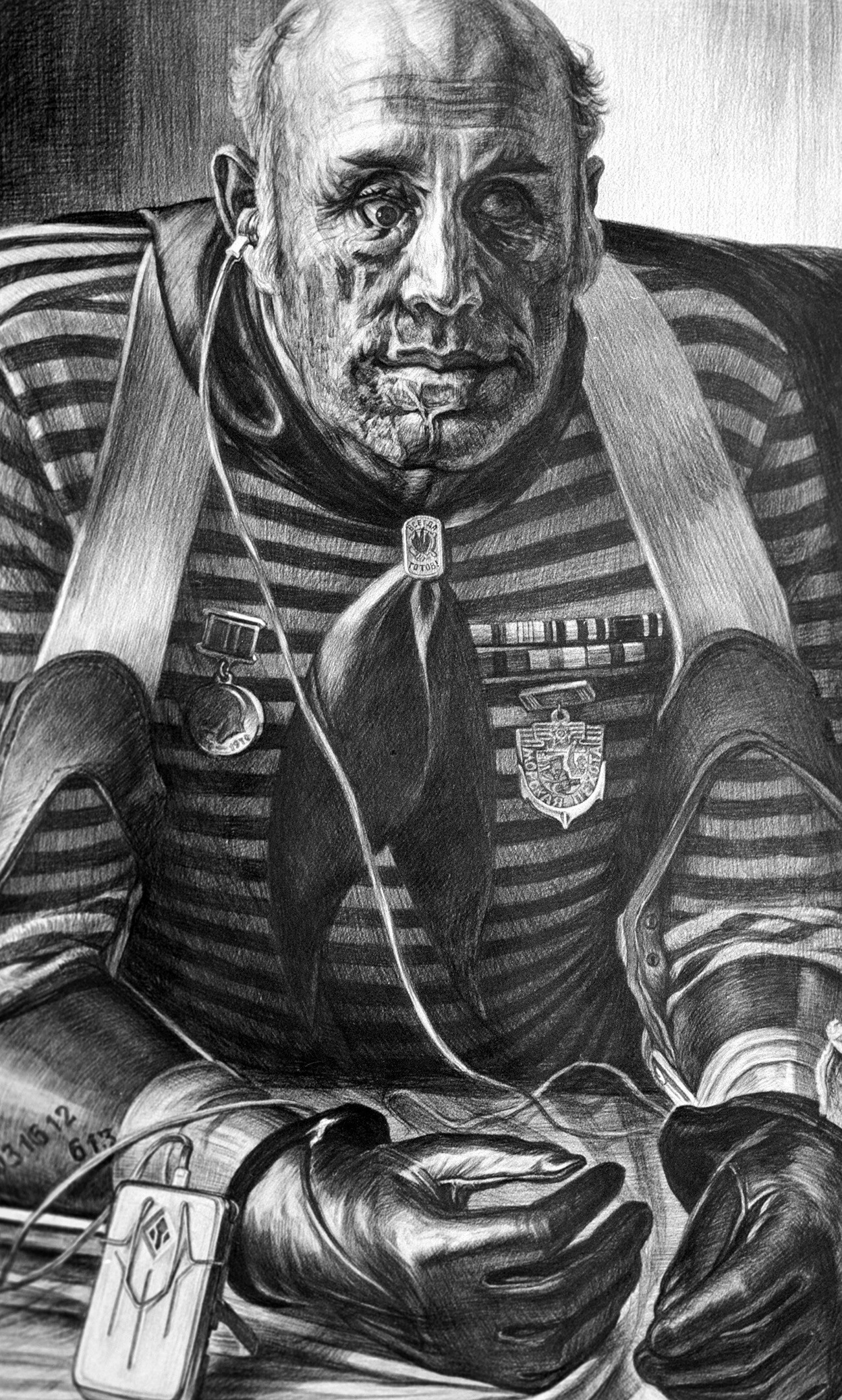

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. Alexey Ckheidze, who called himself a "prosthetic man."

After Kuznetsov’s writings, the almshouse at Valaam monastery was perceived almost like a concentration camp, with low rations and awful conditions. But Semenov points out the numbers of the disabled there: 1952 – 876, 1953 – 922, 1954 – 973, 1955 – 973, 1956 – 812, 1957 – 691. This clearly shows a relatively low death rate for a group of disabled. By the way, the disabled weren’t brought from “all over USSR”, as is often claimed: they were relocated to similar institutions in nearby regions. Classes for shoemakers or accountants were conducted to give the disabled work. Also, many letters and documents were found, proving that any of the disabled were allowed to go home – if they had a home to return to. The documents also show the disabled could really leave at any time, and many did if just to get drunk in town and be brought back by the Soviet police.

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. Valentina Koval from Omsk region.

And the law also treated the disabled specially. A former sanatorium attendant recalled, “Once, a former convict attacked me in the kitchen – a bulky one, and with a prosthetic leg, and you couldn’t fight back – you’ll get sued and lose the trial. He hit me, and I couldn’t retaliate! But the deputy director then came and hit him so hard he bounced off. But he (the former convict) didn’t press charges, he knew he was wrong!”

Gennadiy Dobrov . "Autographs of war" series. Alexey Kurganov from Omsk region.

General major Alexander Gladkov and his wife on a Victory parade on June 24th, 1945.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox