How Georgy Zhukov, the Soviet Union’s greatest military leader, confronted Stalin after WWII

Georgy Zhukov, the Marshal of the Soviet Union.

SputnikWhen Georgy Zhukov, the most prominent Soviet marshal during World War II, died in 1974 after 15 years in retirement and away from public life, the émigré poet Joseph Brodsky wrote a poem called “On the Death of Zhukov.” In the poem, Brodsky called him one of those who “in military formation marched boldly into foreign capitals but returned in fear to their own.”

Perhaps the term “fear” is a bit of poetic license in this case since it’s unlikely that Zhukov, who defeated the Japanese in the battles of Khalkhyn Gol in 1939 and was one of the most successful military commanders throughout the war against Germany, was actually afraid of anything.

Brodsky did have a point though because after the war Joseph Stalin stabbed Zhukov in the back like no foreign adversary could have even dreamed of.

Shooting down a rival

Georgy Zhukov (left among the central three) with Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery and Soviet military commanders in Berlin.

Public domainBy 1946, Zhukov was appointed to command the Soviet occupation zone in Germany and served as commander-in-chief of the Soviet ground forces. He seemed to have a bright future ahead of him. But then everything changed later that year when Stalin stripped Zhukov off all his posts and sent to the remote southern city of Odessa to head a local military district. Quite a humiliating exile for a war hero of this magnitude.

Marshal Zhukov and Joseph Stalin.

Getty ImagesStalin had a flimsy excuse of sorts: Marshal Alexander Novikov, who headed the Air Forces, had claimed Zhukov was conspiring against him. In fact, Novikov was forced to sign this “testimony” against Zhukov under torture. “They broke my morals, I was desperate… sleepless nights… so I signed it, just to stop it,” Novikov would later confess. But this forced testimony is what provided Stalin grounds for accusing Zhukov of “Bonapartism” and sending him into exile.

What really happened is that Stalin wanted to get rid of a potential rival whom he was suspicious and afraid of. Zhukov had become enormously popular during the war--to such an extent that he could have potentially posed a challenge to Stalin’s monopoly on power. As Zhukov himself said when asked why Stalin used false accusations as an excuse to send him into exile, “He was jealous of my glory. And [Interior Minister Lavrenty] Beria fueled that feeling even more.”

Quiet service

Zhukov in Odessa.

SputnikDuring 1946-1948, Zhukov lived in Odessa and spent his time fighting crime–a major step down for a man who led the army that crushed Nazism. Nevertheless, Zhukov showed no signs of insubordination. In 1947, the local authorities announced that organized crime, which thrived following the war, had been defeated. Rumors circulated that Zhukov had sanctioned shooting criminals on sight and without trial. While this could well be just an urban legend, it does reflect the attitude people had towards Zhukov at the time.

In 1948, Stalin sent Zhukov even deeper into the provinces, appointing him commander of the Ural Military District in Sverdlovsk (1700 km east of Moscow). That same year, Zhukov was accused of looting during the capture of Berlin and had to make excuses: “I shouldn't have collected that useless junk and put it into some warehouse, assuming nobody needs it anymore.” He remained in Sverdlovsk until 1953, the year Stalin died.

Back in power

Stalin died on March 5, 1953.

Dmitry Chernov/SputnikJust a month before his death, Stalin ordered Zhukov to return to Moscow. Zhukov figured that Stalin needed his military experience to prepare for a potential war against the West and that this was why his exile had come to an end. Either way, after Stalin’s death Zhukov was appointed Deputy Minister of Defense and played a crucial role in Soviet politics.

He was the one to arrest Lavrenty Beria, one of Stalin’s most powerful and sinister henchmen who is deeply associated with the NKVD--the Soviet Union’s almighty and oppressive secret service. Other officials, including future leader Nikita Khrushchev and lesser-known Georgy Malenkov, who had formed a triumvirate with Beria, plotted against him. Zhukov’s authority in the army helped enormously.

He arrested Beria personally with the help of armed soldiers. “I came from behind, shouted ‘Rise! You are under arrest and pinned his arms as he was rising,” Zhukov recalled his memoirs. Beria was later executed (without Zhukov’s participation).

Against Stalinism

Khrushchev and Zhukov.

Global Look PressMuch like Khrushchev, Zhukov was loyal to Stalin while the leader was alive but went even further in denouncing Stalin’s mistakes and unnecessary and brutal repressions after his death. As historian Leonid Maximenkov notes, Zhukov, while serving as Minister of Defense from 1955-1957, “had his own plan of fighting Stalinism and Stalinists.”

He reopened the cases of military commanders who had been sentenced to death based on false accusations in the 1930s. Several times he managed to punish generals who were responsible for these, firing them from their posts.

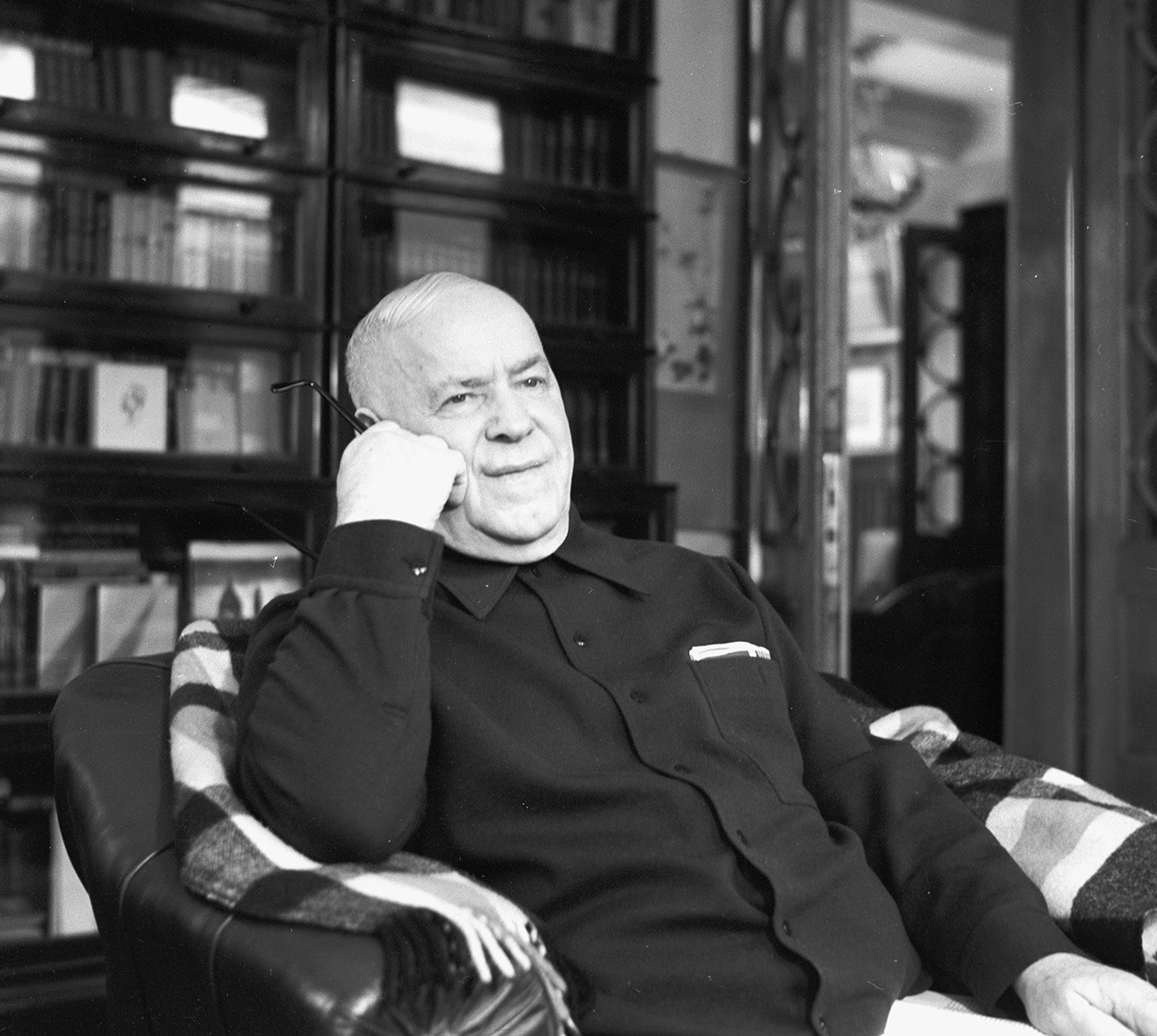

Zhukov in his house.

This, Maximenkov believes, is what prompted Khrushchev to force Zhukov into retirement. Khrushchev knew perfectly well how many officials, including ones at the highest posts and he himself, were involved in the dirty business of the 1930s. Purging members of the apparatus who were implicated in the crimes of the 1930s would risk damaging the entire Soviet system. So in 1957, the new leadership forced Zhukov to retire, accusing him of having consolidated his power too much.

This time his military career actually did come to an end. He spent the rest of his life writing memoirs and giving occasional interviews, mostly about the war and hardly mentioning the period of unscrupulous intrigues that came afterwards.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox