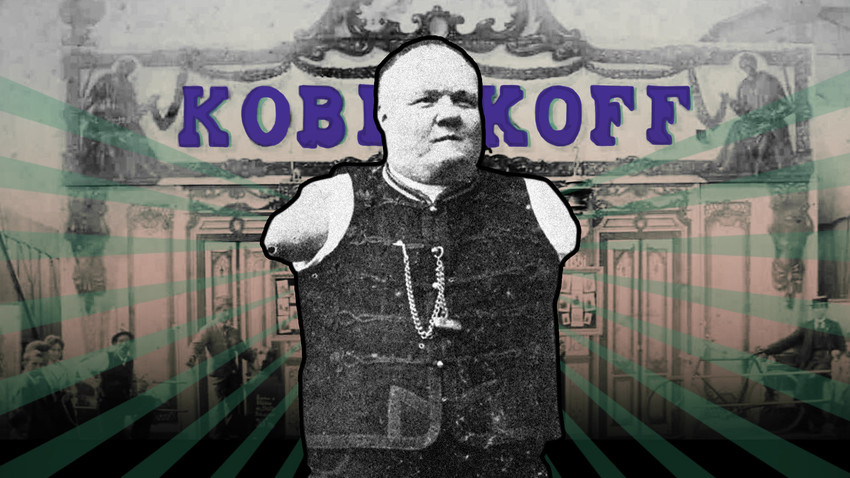

The armless, legless Russian aristocrat who wowed the world

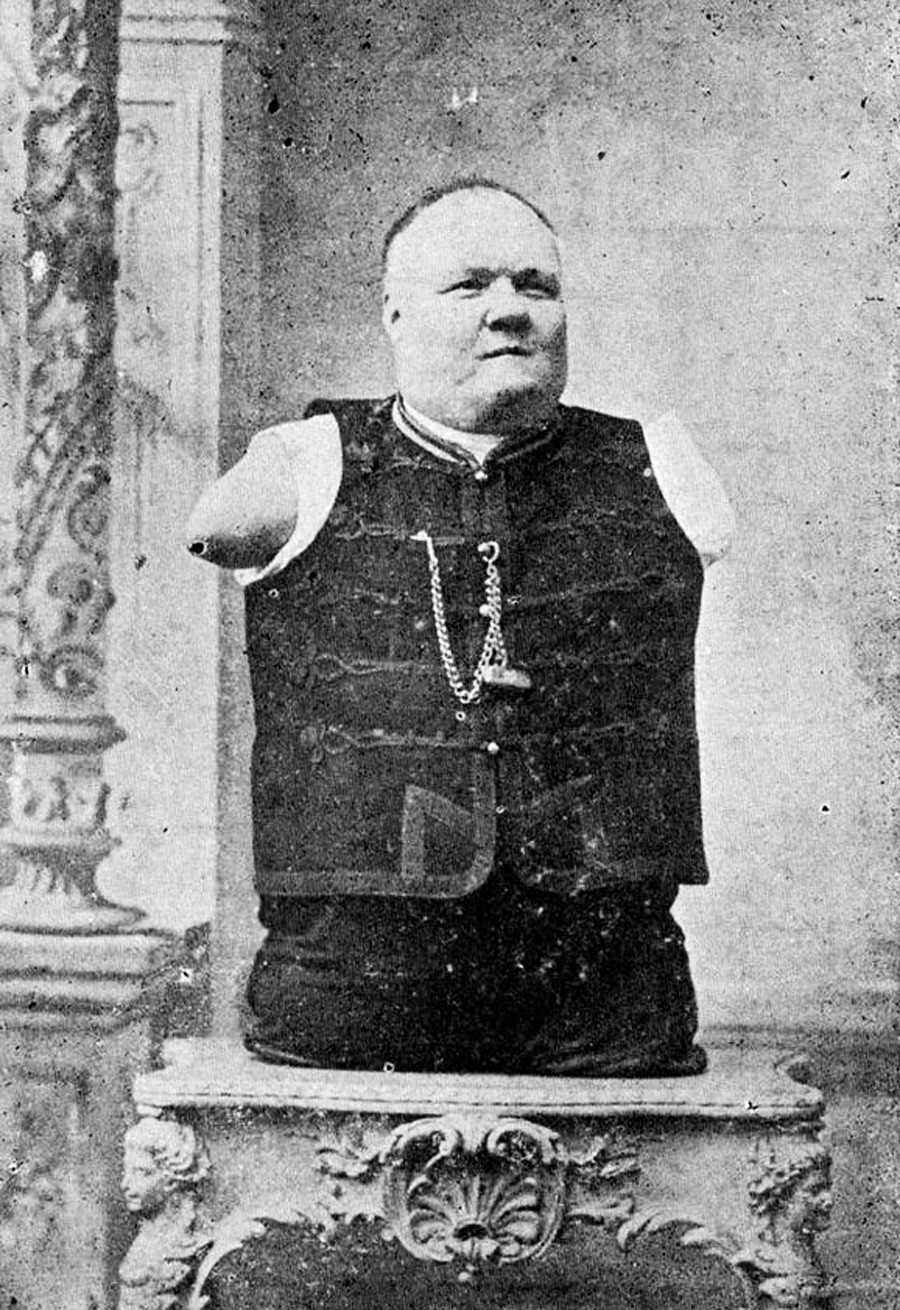

Nikolai Kobelkoff was born in 1851, however without any limbs, most likely due to constriction ring syndrome, a congenital disorder with an unknown cause. But the 14th child in a wealthy family of the governor of Voznesensk, a town in the Ural mountains, showed great vigor: although he could only use a stump on the place of his right arm, he learned to dress and to eat by himself.

Nikolai Kobelkoff (1851 – 1933)

Archive photoIn the 1880s, prosthetic limb manufacturer, James Gillingham, saw Kobelkoff in person in Europe and described him. Among his observations, he noted that Kobelkoff had “the rudiments of legs – one thigh being six inches long, the other being about two inches longer – but for a right arm he has merely a conical mound, and for left arm a rounded bone.”

Nikolai was resourceful from an early age. He learned to write holding a pen between his stump and his head, and at 18, worked as a clerk. “He sits at a table, fixes a pen between his cheek and arm, and writes away in a good, clear, commercial hand. And with the same combination of cheek and shoulder, he does most of the other things, the most seemingly difficult being that of feeding himself,” Gillingham witnessed later.

If it wasn’t for Nikolai’s immensely positive attitude and outlook on life, he’d hardly have been able to make such an astonishing career as he went on to have. Apart from not having any limbs, he was gifted with immense body strength, that allowed him to pick himself up without any additional help, walk on his leg-stumps and even lift weights! His happy demeanor and impeccable aristocrat manners were also the features that made Nikolai so appealing, despite his disability.

In 1870, an entrepreneur offered him a tour to St. Petersburg. His act was simple but still fascinating. “The way he threads a needle is to take it in his mouth and stick it in his jacket, and then putting the thread in his mouth pass it through the eye. The strangest thing is to see him load a pistol, aim it at a lit candle, and shoot the flame out.”

While on a tour in Vienna, Nikolai met Anna Wilfert, a relative to the owners of a spot in Vienna’s Prater Park where Nikolai had performed once.

Nikolai Kobelkoff and his wife Anna

Archive photoAfter marrying him in 1876, Anna joined him as an assistant in his performances. Anna became the mother of their 11 children, many of them were born while touring. 6 of them survived, and they didn’t in any way carry their father’s disorder.

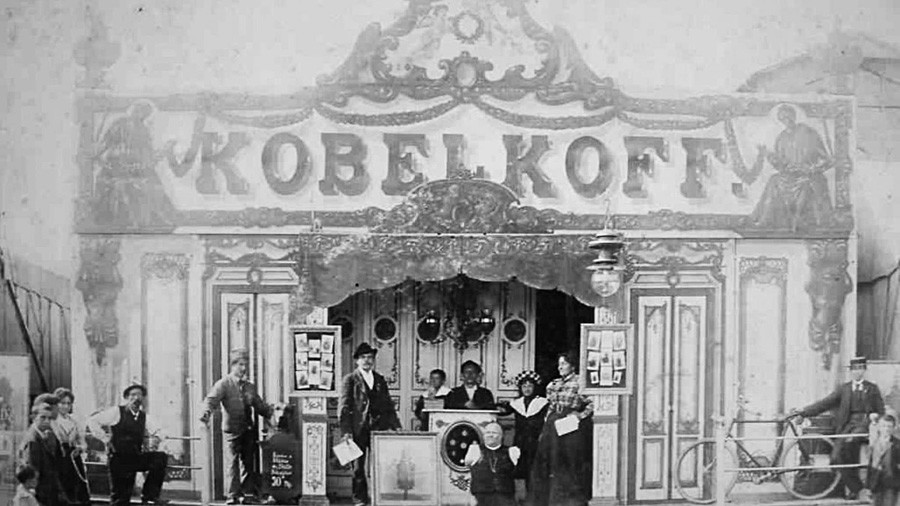

The Kobelkoff family at their pavilion at Prater

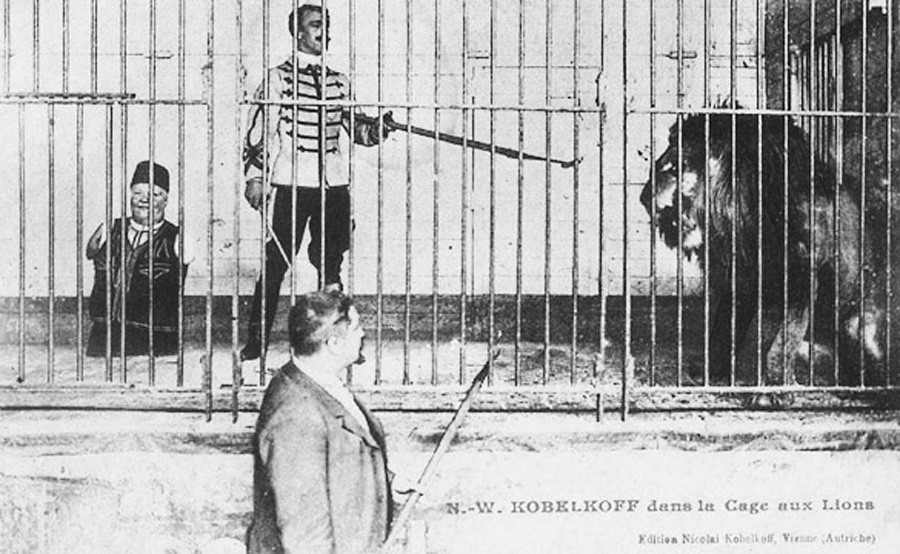

Archive photoBy the 1880s, Kobelkoff, who often did his shows under the “Rumpfmensch” (“Human Trunk”) moniker, developed his act: the highlight was him getting out of a cage with a lion. He toured Europe and in 1882, the USA.

Nikolai Kobelkoff and his son in a lion's cage

Archive photoWhile touring, he didn’t spend his time idling: he mastered Italian, English, Hungarian and Czech, in addition to the French and German he already knew. He performed his shows before several monarchs, including Tsar Alexander III, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, and Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria.

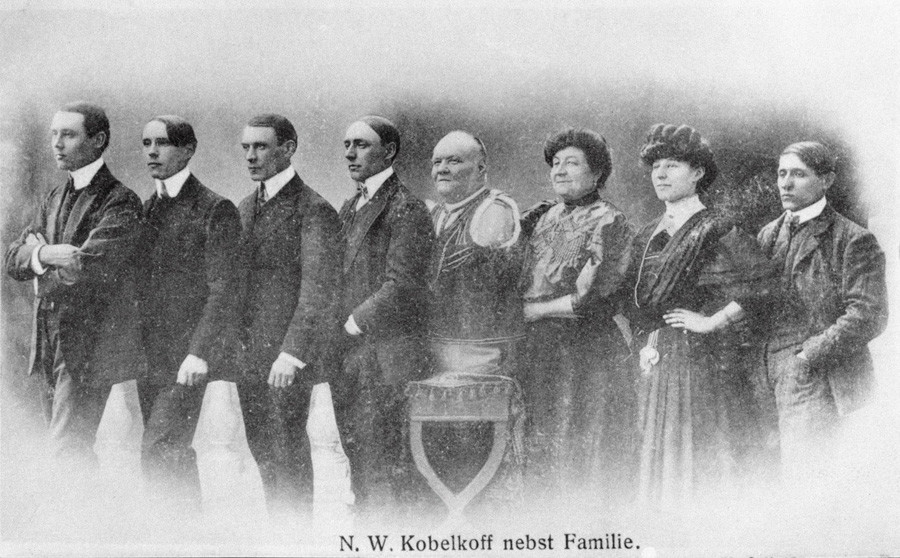

The Kobelkoff family

Archive photoBy 1901, Kobelkoff had saved enough money to buy a plot of land in Vienna’s Prater Park from his wife’s relatives. Nikolai ordered a velodrome and a slide to be built on the site, and earned money off these rides, but continued to tour.

Nikolai Kobelkoff in his later years

Der Prater, 2016His children, one by one, became old enough to join him on tours. In 1912, his wife Anna passed away because of a stroke, and from that moment on, Nikolai stopped touring and retired in Vienna, where he lived in the company of his children and grandchildren and continued to run the business.

The Kobelkoff family gravesite at the Vienna Central Cemetery

Papergirl (CC BY-SA 4.0)He died in 1933 at 81 years of age and was buried at the Vienna Central Cemetery. Income from the rides in Prater park has supported his descendants until the 1970s.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox