How did the Soviets react to the fall of the Berlin Wall?

Mikhail Gorbachev didn't bring the wall down - but he didn't top the process either.

Getty Images, Russia BeyondA week before the fateful events of November 9, 1989, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev met with the then-new (and last ever) leader of the German Democratic Republic, Egon Krenz. East Germany had been up in arms by that point, demanding democratization and open borders with West Germany (the Federal Republic of Germany - or the FRG, as it was known in the East). A strict border-crossing regime was still in place, but the GDR’s population had long been determined to cross over to the capitalist side, with Hungary having opened the border with Austria in 1989.

Gorbachev, whose ideology was rooted in the doctrine of New Thinking - one that offered freedom of choice to members of the socialist bloc - actually had nothing against the democratization drive of the East Germans, but nonetheless could not have foreseen that the name “GDR” was about to disappear from the map forever.

Gorbachev meeting Egon Krenz, East Germany's last leader.

Getty Images“Our mutual thinking with Krenz at the meeting had been that the question of German reunification was ‘still not relevant’, ‘not really on the agenda’, and that is where we were coming from,” he writes in his memoirs. A mere week later, the concrete border symbolizing the division between the two countries fell.

A misunderstanding

According to Ivan Kuzmin, who had until 1989 been stationed at the KGB’s branch in the GDR, even when 9 November arrived, and Politburo member Gunter Schabowski declared the border to West Berlin open, no one was any the wiser to what was about to take place. “It was a regular announcement, nothing out of the ordinary. I did not foresee the speech arousing any sort of major reaction at all,” he writes.

Schabowski’s only role was to report at a press conference that the GDR had set up new exit regulations at the state border crossing. But he made two crucial mistakes.

One press-conference that changed the destiny of the East Germany.

Getty ImagesFirst, he’d confused the state border with the border between East and West Berlin - a crossing that was regulated by the Allies (USSR, USA, Great Britain, and France), and not East German authorities. It was the allies who’d set up the crossing after the end of the war. “Before changing something in Berlin, the GDR was to inform the USSR of its intentions,” Igor Maksimychev, a diplomat posted there at the time, emphasizes.

The second mistake Schabowski made was that - in answering the question on when these new regulations were to go into effect - he gave in to momentary confusion, and said “Immediately”, when, in fact, they weren’t supposed to be on for another 24 hours, on November 10.

As a result, massive crowds in East Berlin rejoiced and made their way to the Wall in anticipation of being let through.

“The real heroes on the night of the 9th and the morning of the 10th were the border guards of the GDR”, Maksimychev believes. They did not opt to open fire, and in so doing saved countless lives. The border inside Berlin - even without the Communist party’s go-ahead - was then considered to be open in earnest. And it is on that day, on November 10, that the Wall had begun to be dismantled, its first chunks split into souvenirs.

Moscow approves

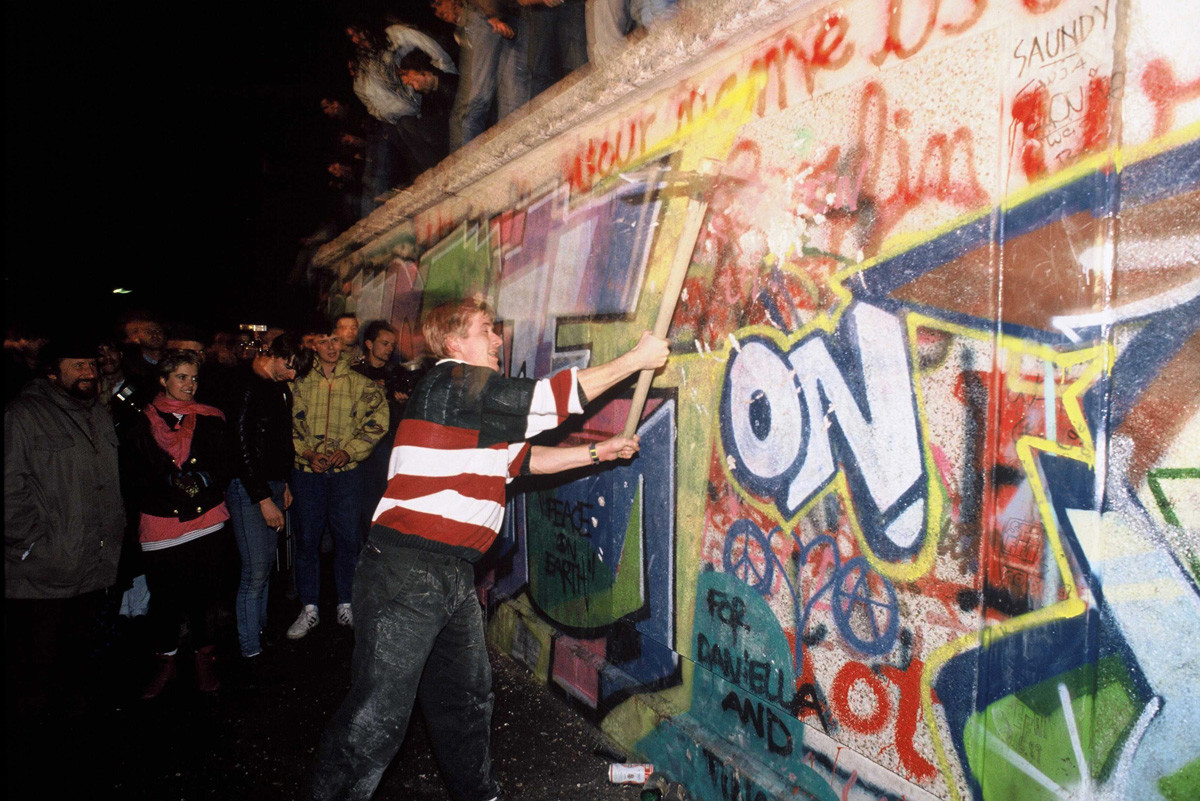

Fall of the Berlin Wall.

imageBROKER/Global Look PressGorbachev had not planned for such a turn of events, but it would be an overstatement to say that he was taken aback by the developments. On the same day the Berlin Wall had started to be taken apart, he sent a message to Krenz (who himself had little say in the matter at that point), that he approved of the border’s opening.

“I think it was a secret dream of Gorbachev’s to one day wake up to the news that the Wall had disappeared on its own,” the General Secretary’s then-press secretary Andrey Grachev believes. Gorbachev had been against German partitioning all along but sought to avoid any personal involvement in the matter. “And that is what ended up happening.”

Gorbachev, for his part, underlines that he wasn’t going to interfere with the will of the German people and employ Soviet forces on the GDR’s doorstep. “We had taken every possible step to ensure that the process was peaceful, did not go against our country’s interest or threaten European peace in any way.”

At the end of the 20th century, rapid change began sweeping over the world. In October of 1990, the former GDR was absorbed by the FRG, while a year later, in December 1991, the USSR itself ceased to exist, breaking apart into 15 independent states. “The Russians were now tasked with putting up new walls along the borders of these now ex-Soviet republics,” author Dmitry Bykov notes in an article on the final days of the Berlin Wall.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox