How British writer Arthur C. Clarke TRICKED a famous Soviet sci-fi mag

1.7 million copies – that’s how much the Tekhnika-Molodezhi (youth engineering) magazine used to sell to Soviet sci-fi aficionados every month.

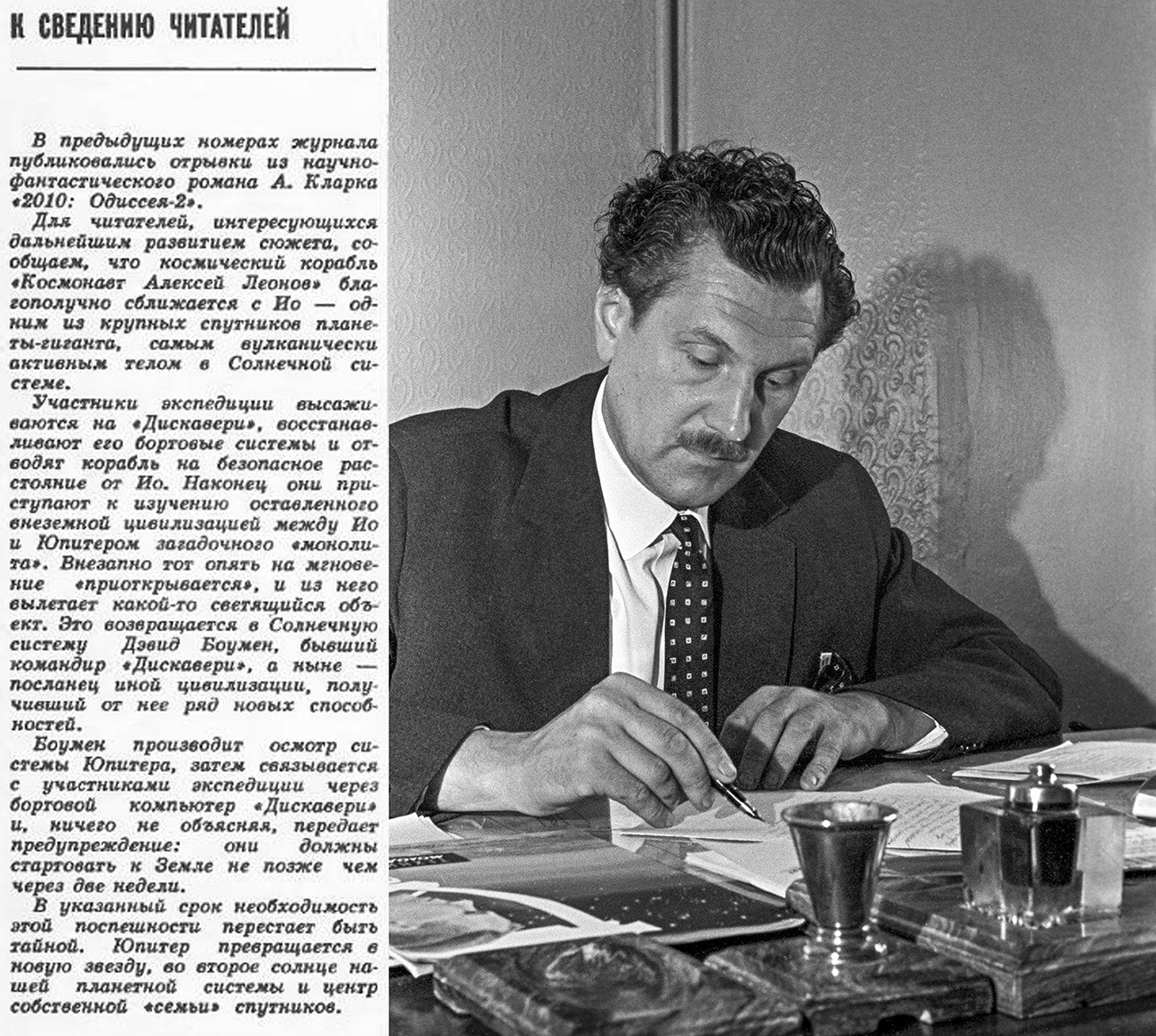

The incredible success of the magazine was attributed not only to the Soviet people’s love for engineering and sci-fi stories, but also thanks to the efforts of its editor-in-chief, Vasily Zakharchenko.

The success of the magazine the efforts of its powerful editor-in-chief, Vasily Zakharchenko.

Sergey Ivanov-Alleluyev/ТАSSA war veteran and a renowned editor, Zakharchenko was an influential man, decorated for his war and literary achievements. The wide circulation of the magazine he led as editor-in-chief from 1949 to 1984 only contributed further to his fame and power within the Soviet publishing world.

One of the most notable manifestations of Zakharchenko’s power was that he, as the editor-in-chief of a tremendously popular magazine, had a carte-blanche for publishing fictional stories by English-speaking authors from capitalist countries.

Zakharchenko had a carte-blanche for publishing fictional stories by English-speaking authors from capitalist countries.

Robert Avotin/Tekhnika Molodezhi, 1980One of the most famous of such writers was Arthur C. Clarke, the award-winning British writer, explorer, and co-author of 2001: A Space Odyssey script, in collaboration with Stanley Kubrick. A Russian translation of his widely praised novel The Fountains of Paradise was first published on the pages of Zakharchenko’s Tekhnika-Molodezhi magazine in 1980. 1.7 million Soviet people were reading the novel in monthly installments.

A Russian translation of Arthur C. Clarke's novel was first published on the pages of Zakharchenko’s Tekhnika-Molodezhi magazine in 1980.

Getty ImagesThe novel was so successful that when Clarke decided to visit the country in 1982, he was welcomed, among others, by Alexei Leonov, the first man to conduct a spacewalk and the literary editor Zakharchenko. The British writer and the Soviet editor found common ground and soon enough the Russian translation of Clarke’s next novel, 2010: Odyssey Two, hit the pages of Tekhnika-Molodezhi.

The novel was so successful that Clarke decided to visit the country in 1982.

Tekhnika Molodezhi, 1982In the book, a spaceship named “Alexei Leonov” and manned with a Soviet-American crew goes to Jupiter to solve the mystery of the lost Discovery spaceship. Soviet readers enjoyed the first two chapters of the new novel very much… up until the following issue, where they found a brief synopsis of the book instead of the much-anticipated literary narrative.

In the book, a spaceship named “Alexei Leonov” and manned with a Soviet-American crew goes to Jupiter to solve the mystery of the lost Discovery spaceship.

Tekhnika Molodezhi, 1982As it turned out, Arthur C. Clarke had tricked Soviet editor Zakharchenko into publishing the novel where the names of the main characters were swapped to the names of famous Soviet dissidents, some of whom were confined in labor camps.

The International Herald Tribune broke the story in March 1984 and one of the dissidents whose name was featured in the novel called the author’s move “a small but elegant Trojan horse”. Needless to say, the Soviet party leaders hated being mocked like that by their ideological enemies. A scapegoat had to be found immediately.

“Before this episode, our editor Vasily Zakharchenko could walk into the highest offices [in the Soviet Union]. But after [publication of] Clark's novel, the attitude towards him changed dramatically. Zakharchenko (who had just received another prize of the Lenin Komsomol) was literally eaten alive, smeared on the wall,” recalled later Zakharchenko’s deputy, Alexander Perevozchikov, who replaced the disgraced editor-in-chief.

After the Soviet party leaders had been mocked by their ideological enemies, a scapegoat was found immediately.

Tekhnika Molodezhi, 1984. Boris Vdovenko/SputnikZakharchenko’s life was ruined: he not only lost his office, but he was no longer invited to TV and radio shows, where he had previously been welcome.

Ironically, only a few years later, Gorbachev’s politics of glasnost (openness and transparency) turned everything upside down: it was no longer viewed as a despicable fault to print Clarke’s novel and the same magazine that had previously withdrawn it from publication, ended up printing the remaining chapters in 1989 and 1990.

Click here to marvel at 10 Russian sci-fi covers that need to be burned before reading!

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox