FAKE OR NOT: A soldier of three emperors

In 2013, on Novy Venets Boulevard in Ulyanovsk, a monument was to be erected to honor Vasily Kochetkov, a famous native of Simbirsk Governorate and “soldier of three emperors”. But the public was outraged. Why? you might ask. Surely it wasn’t because someone wanted to glorify Russian military exploits? Not at all.

The point was that local historians and archivists rightly asked: Where is the evidence of Vasily Kochetkov's incredible heroic deeds? All the information about his exploits comes from just one source – an article titled A Remarkable Soldier published in the Government Gazette (Pravitelstvenny Vestnik) on Sept. 2, 1892. In October, the same article was reprinted in the Bulletin of the Military Clergy (Vestnik Voyennogo Dukhovenstva) and then again, in January 1893, in the extremely popular weekly magazine World Illustration (Vsemirnaya Illyustratsiya). What did it say about Kochetkov?

A fighting man

A draft of the monument to Vasiliy Kochetkov

Ulyanovsk governmentThe article begins: "In Belozersk, Novgorod Governorate, on May 30 of this year, one of the longest-serving soldiers of the Russian Army, retired bombardier of the Life Guards Horse Artillery Brigade Vasily Kochetkov, died from sudden cardiac arrest while traveling from St. Petersburg to the region of his birth, the Simbirsk Governorate. He was 107 years old and 60 of those years were spent by him on active duty as a soldier."

According to the article, Kochetkov was born in 1785 in the family of a soldier and was enlisted as a cantonist at a garrison school. He began as a regimental musician, but at the age of 26 entered active service with the Life Guards Grenadier Regiment, an elite unit of the Imperial Army. Men had to be particularly tall - strapping bogatyrs - to be accepted into the regiment. Kochetkov was at the Battle of Borodino and the capture of Paris. Then, as a soldier of the Pavlovsky Regiment, he fought in the 1828-1829 Russo-Turkish war, took part in the suppression of the 1830-1831 Polish Uprising and the capture of Warsaw.

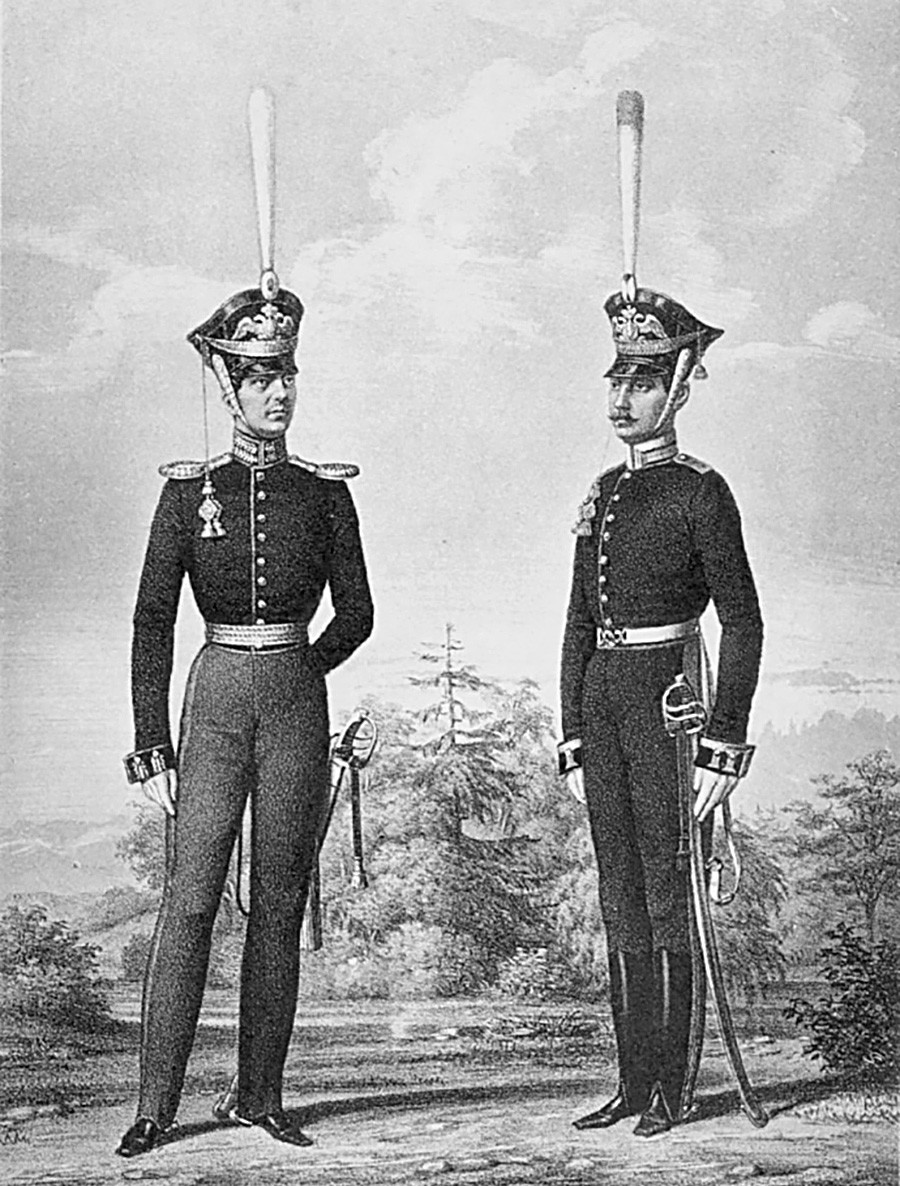

Life Guards Horse Artillery Brigade uniforms: chief officer (L), fireworker (R)

In 1833, at the age of 48, he began service in the Life Guards Horse Pioneer Squadron, and in 1843 was transferred to the Caucasus where he served in the 17th Nizhny Novgorod Dragoon Regiment, the fiercest military unit of the Russian Imperial Army. Noblemen demoted for dueling served in it as soldiers. In the Caucasus, Kochetkov was wounded twice; he was also captured but escaped.

At the age of 64, Kochetkov was forced to sit an exam to qualify for officer rank, but in the event he turned it down - he wanted to be a soldier. After receiving a pay increase and silver stripes on his uniform, he retired in 1851. But in 1853 he returned to the army – to defend Sevastopol in the Crimean War.

Khiva campaign of 1873. Russian troops are crossing the death sands to the wells of Adam-Krylgan, by Nikolay Karazin, 1888.

State Russian MuseumIn 1862 he became a palace grenadier. In 1869 he went to serve in Turkestan. Furthermore, according to the article, Emperor Alexander II personally saw off the 84-year-old Kochetkov as he departed for the war. In 1873 Kochetkov took part in the Khivan campaign, a three-month march across the desert.

Subsequently, Kochetkov was enlisted into the railroad escort protecting the imperial train, and, in 1876, the 92-year-old veteran volunteered to fight against the Turks for the liberation of Serbia and Montenegro. As a result, Kochetkov participated in the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish War, in which he lost his left leg. For another 13 years, until 1891, he served in the Life Guards Horse Artillery Brigade. In the course of his army career, Kochetkov participated in 10 military campaigns, was wounded six times and was awarded 23 crosses and medals.

Incredible? That is what the historians thought too.

What is the truth here?

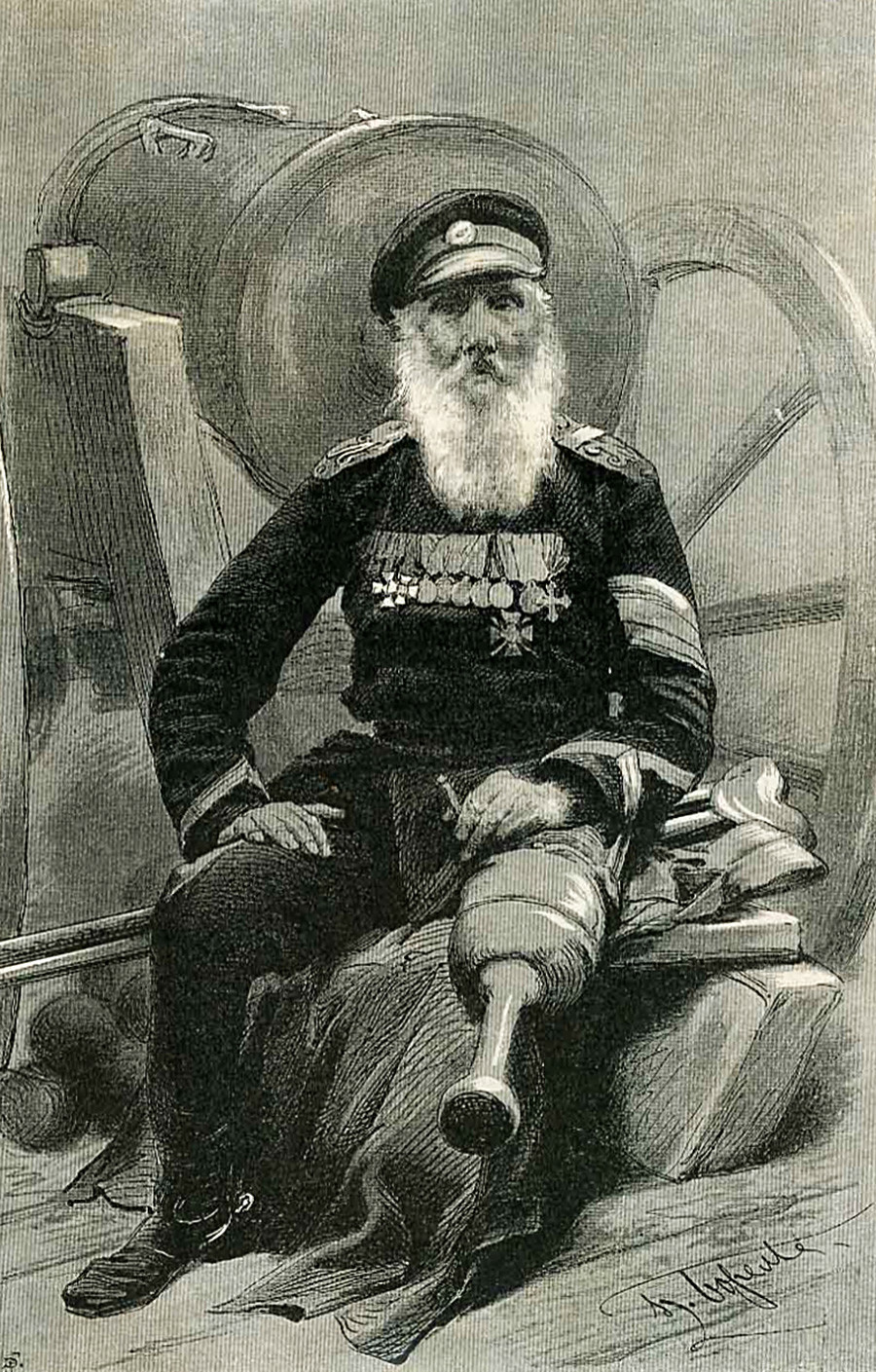

Portrait of Vasiliy Kochetkov by Pyotr Borel, 1892.

Public domainThe only existing portrait of Vasily Kochetkov was created by artist Pyotr Borel from a photograph taken on May 20, 1892, 11 days before Vasily Nikolayevich [Kochetkov] died in Vytegra in Olonets Governorate. At the time Borel was a respected 63-year-old artist, very popular for his Gallery of the Russian Heroes and Chief Commanders in the 1853-1856 Crimean War, published in the years 1857-1863.

Journalist Sergei Tyulyakov, who did his own research, quotes (link in Russian) reminiscences about Pyotr Borel: He was "scrupulous and meticulous, and checked everything. Especially when he made engravings from drawings by other artists". Let's suppose that the person painted by Borel was indeed someone by the name of Vasily Kochetkov. But then what about his exploits? Are they fake or not? We suggest you decide for yourself - we shall simply provide you with the arguments for and against.

Arguments against

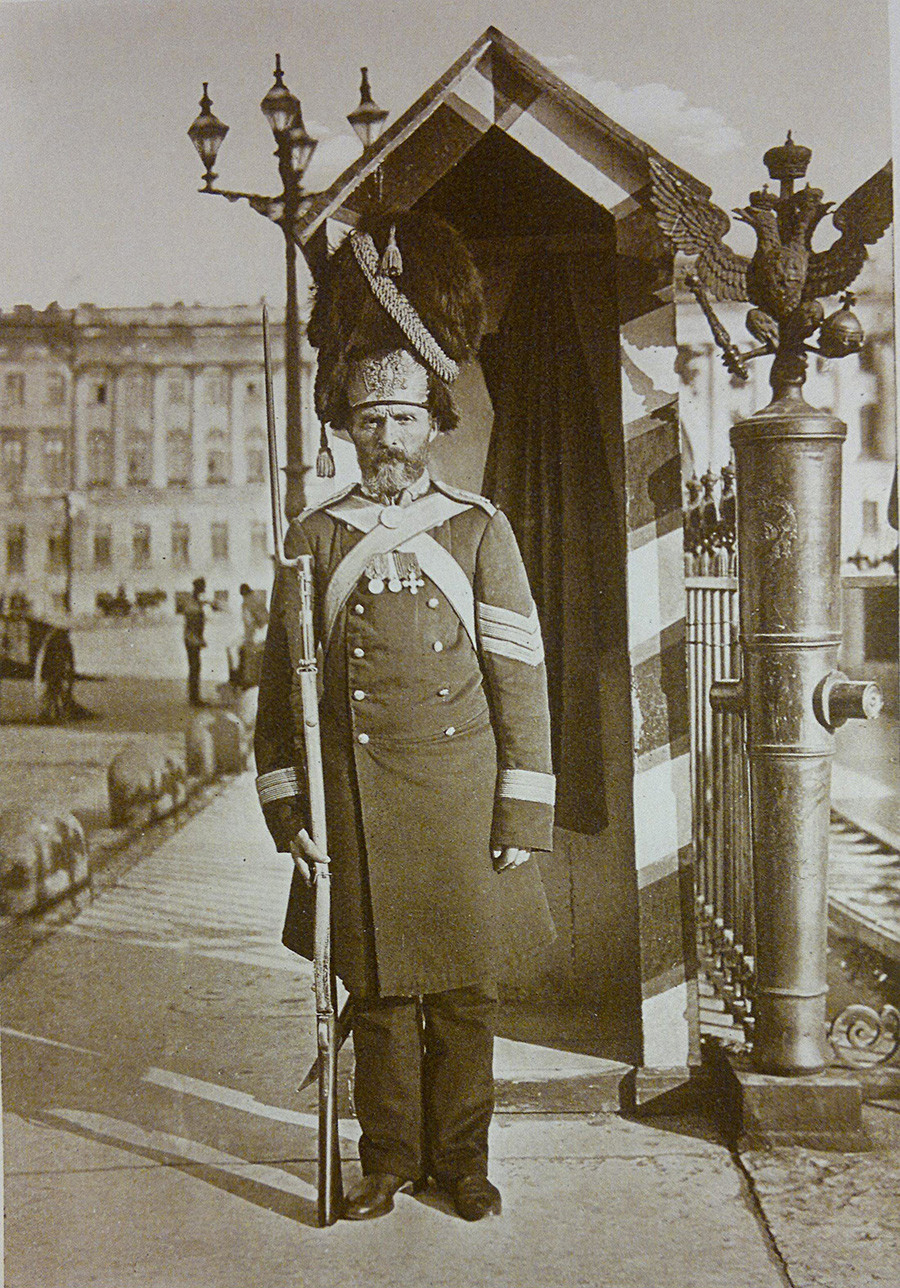

NOT KOCHETKOV, but some palace grenadier on duty near the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg

Archive photoThere is no information about Kochetkov in the Ulyanovsk historical archive. But in 1864 many documents were lost in a fire. Kochetkov was never mentioned by historians or memoirists, and even the gubernatorial scientific archive commission which especially sought out such cases said nothing about him.

On the engraving, Kochetkov wears only 10 medals, but the article mentions 23. Ulyanovsk researcher Vasily Akhmerov published a reply given by the Russian State Archive of Military History to an official request regarding Kochetkov. The archive's director, merited archivist Irina Garkusha, points out that on the engraving Vasily Kochetkov is shown wearing the "uniform of the Life Guards Horse Artillery Brigade with stripes for long service… One wide shoulder mark is visible on the shoulder straps - the insignia denoting the rank of feldwebel or wachtmeister (corporal). It is also possible to pick out the monogram "A" (probably for Emperor Alexander II) on the shoulder straps. On the chest… is a medal ribbon consisting of two crosses, six medals (impossible to identify) and the Romanian Iron or Danube Cross (awarded for the Crossing of the Danube in the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish War). Below the medal ribbon is a cross for service in the Caucasus."

Romanian cross "For crossing the Danube 1877"

Public domainHere we have objective information about Vasily Kochetkov. His two crosses are "service” medals - the Orders of St. George 3rd and 4th Class, which were worn together; they are marks of honor but not unique, and the same goes for the Danube and Caucasus crosses.

Cross "For the service in the Caucasus"

(CC SA 1.0)The article says: "His uniform presented a rare phenomenon, being decorated on the shoulder straps with the joint monograms of three late emperors: Alexander I, Nicholas I and Alexander II (hence his nickname of the "soldier of three emperors" – ed.), and on the left sleeve with eight rows of service stripes of gold and silver lace and braid; and around his neck and on his chest Kochetkov had 23 crosses and medals." But, as we can see, there are neither eight rows of stripes nor 23 medals.

And, finally, there is no record or any information to the effect that Alexander II personally saw Kochetkov off to Turkestan. And it is highly doubtful that, at the age of 93, Kochetkov could have survived in field conditions after losing his leg and that, moreover, he could have remained in the army subsequently. Would the great surgeon Nikolay Pirogov, who was surgeon-general of the Russian army in those years, have missed such a unique case, and not described it? There are no answers to all these questions.

Or is it not a fake story?

"Portrait of Piotr Vannovsky" by Alexander Pershakov

Hermitage MuseumDocuments relating to V. N. Kochetkov can in fact be found in the Russian Archive of Military History. First of all, there is a telegram from V. Ye. Stroganov, a doctor at Belozersk hospital, which is addressed to the General Staff. Stroganov asks for permission to bury Kochetkov with military honors. This is how Stroganov describes Kochetkov: "A holder of the Order of St. George 2nd Class who participated in all the battles from Borodino to Shipka, and who was accompanying the Sovereign during the train crash on Oct. 17 [1888]". Minister of War Pyotr Vannovsky had doubts about the information and gave instructions for it to be verified, and a letter to this effect was sent to the Belozersk district military commander.

There is no further mention of Kochetkov in any other documents. In their reply, the archive pointed out that "Vasily Nikolayevich Kochetkov is not listed in the archive's references relating to servicemen of the Russian Army". The lists of military units in which Kochetkov may have served were not checked but, according to the archive's director, such a search "would involve time-consuming and laborious work without any guarantee of achieving a positive result".

We still have what is surely the main piece of evidence: The portrait of Vasily Kochetkov. According to Sergei Tyulyakov, he is depicted not in parade uniform but in his service dress, which means that Kochetkov simply may not have put on all of his 23 decorations. The Danube and Caucasus crosses are separated by a gap of about 20 years, but an old soldier could have taken part in the Caucasus campaign as well as the liberation of Bulgaria. And the service stripes (albeit not eight) are indeed visible on his sleeve. And there are people with the same surname still living in the village of Spasskoye where Kochetkov was born. True, none of them can say for sure that they are his relatives or descendants.

Konstantin Sluchevsky

Engraving after photo by S. LaptevArguably the main question is the following: Could the Government Gazette or World Illustration have falsified the information about Kochetkov?

In 1892 Russia was re-arming. It had concluded an alliance with France against Germany and Prussia, which were ruled by the unstable and impulsive Wilhelm II. The army was going through reorganization, spending cuts and reshuffles - all this was undermining its prestige in society. Let's recall when the article came out - on Sept. 2, 1892, when celebrations marking the 80th anniversary of the Battle of Borodino were still underway, and Kochetkov, according to the article, had taken part in it. Finally, the story is still being discussed and critiqued today, and, if it had not been for a few doubters, a monument to the "soldier of three emperors" would already have been erected in Ulyanovsk.

The chief editor of the Government Gazette was Konstantin Sluchevsky. The son of a senator and top student at the First Cadet Corps, he received a Doctor of Philosophy degree abroad and returned to Russia. For seven years he worked for the Ministry of Internal Affairs and another 17 years for the Ministry of State Property, and in 1891, in the rank of a government official for special assignments 5th class (a very high rank) was appointed editor-in-chief of the main newspaper of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. At the same time, Sluchevsky was actively engaged in literary and journalistic work, and widely known as a symbolist poet. In his youth, he criticized the ideas of radical writers Dmitry Pisarev and Nikolay Chernyshevsky, and in the late 1880s accompanied Grand Duke Vladimir Alexandrovich (the younger brother of Emperor Alexander III) on a trip around Russia. In other words, he was a "seasoned" functionary and even held the court title of Hofmeister. Was Sluchevsky capable of a "small" falsification for the glory of the Russian Army? Make up your own mind.

As for Vasily Nikolayevich Kochetkov, we can definitely say the following: Most likely such a soldier - a veteran and hero of several wars, and the holder of two Order of St. George service medals, as well as of the Danube and Caucasus Crosses - did exist. But his military exploits were in all probability exaggerated. It is possible that the service records of several different soldiers were "merged" in his biography. Anyway, documents relating to the village of Spasskoye, in which Kochetkov was born, are still waiting to be researched. So there may yet be a final chapter to this story.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox