How Soviet scientists drifted on an ice floe for 274 days

Pyotr Shirshov, Ernst Krenkel, Ivan Papanin, Evgeny Fyodorov.

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruJune 6, 1937, is an important milestone in the history of Arctic exploration. It was on this day that Soviet scientists officially opened the world’s first polar research drifting station, North Pole-1.

Ivan Papanin, Ernst Krenkel, Pyotr Shirshov, Evgeny Fedorov.

МАММ/МDF/russiainphoto.ruThe four expedition members and their dog Vesely (Merry) became temporary inhabitants of a huge ice floe measuring three by five kilometers, and just over three meters thick. The plan was to carry out research as the ice floe drifted south towards Greenland.

In the 1930s, exploring the harsh Arctic environment was far more complicated and dangerous than in the modern era of nuclear icebreakers. The drifting station was designed for conducting research almost year-round, which would have been impossible by any other means. The scientists at North Pole-1 were tasked with performing meteorological observations, collecting hydrometeorological, hydrobiological, and geophysical data, measuring the ocean depth along the route of the ice floe, and taking bottom soil samples. In addition, they were instructed to supply radio communications and weather reports to Valery Chkalov and crew during the latter’s first non-stop flight from the USSR to the US over the North Pole.

To be on the safe side, the station was supplied with food for 700 days. No one expected the expedition to last that long, but the explorers were conscious that some of it would spoil, and they were right. “We brought 150 kilograms of dumplings from the mainland,” wrote Ivan Papanin, head of North Pole-1, in his memoirs Ice and Fire. “They were frozen, but over the long journey and during the spring it all turned into mush and smelled horrible. I had to chuck it away and use pork and beef carcasses instead. There was more bad news at the pole: the rump steaks lovingly prepared by top chefs were also inedible.” The explorers tried to shoot a sea hare and a family of polar bears that had wandered onto the ice floe, but without success.

The polar explorers were housed in a canvas tent almost four by four meters, insulated with two layers of eiderdown. And knowing which types of snow make for the best building materials, they made themselves a “snow palace.” For their research work, they were equipped with special rubberized tents, two clipper boats, two kayaks, and light sleds.

The station drifted south at a fair clip, about 20 miles per day. “The ice floe required continuous hard work. In the first weeks, we were so tired that sometimes I couldn’t even pick up the pencil to make a diary entry,” Papanin recalled.

The Arctic summer, a few degrees above zero with alternating rains and snowstorms, completely severed the station from the mainland — there was no way a plane could land on the floe, which was covered with deep icy water. “There are so many lakes on the ice they ought to be given names... I went to have a look at all the water running over our ice floe. There was even a waterfall in one place. If you fell down it, there was no getting out.”

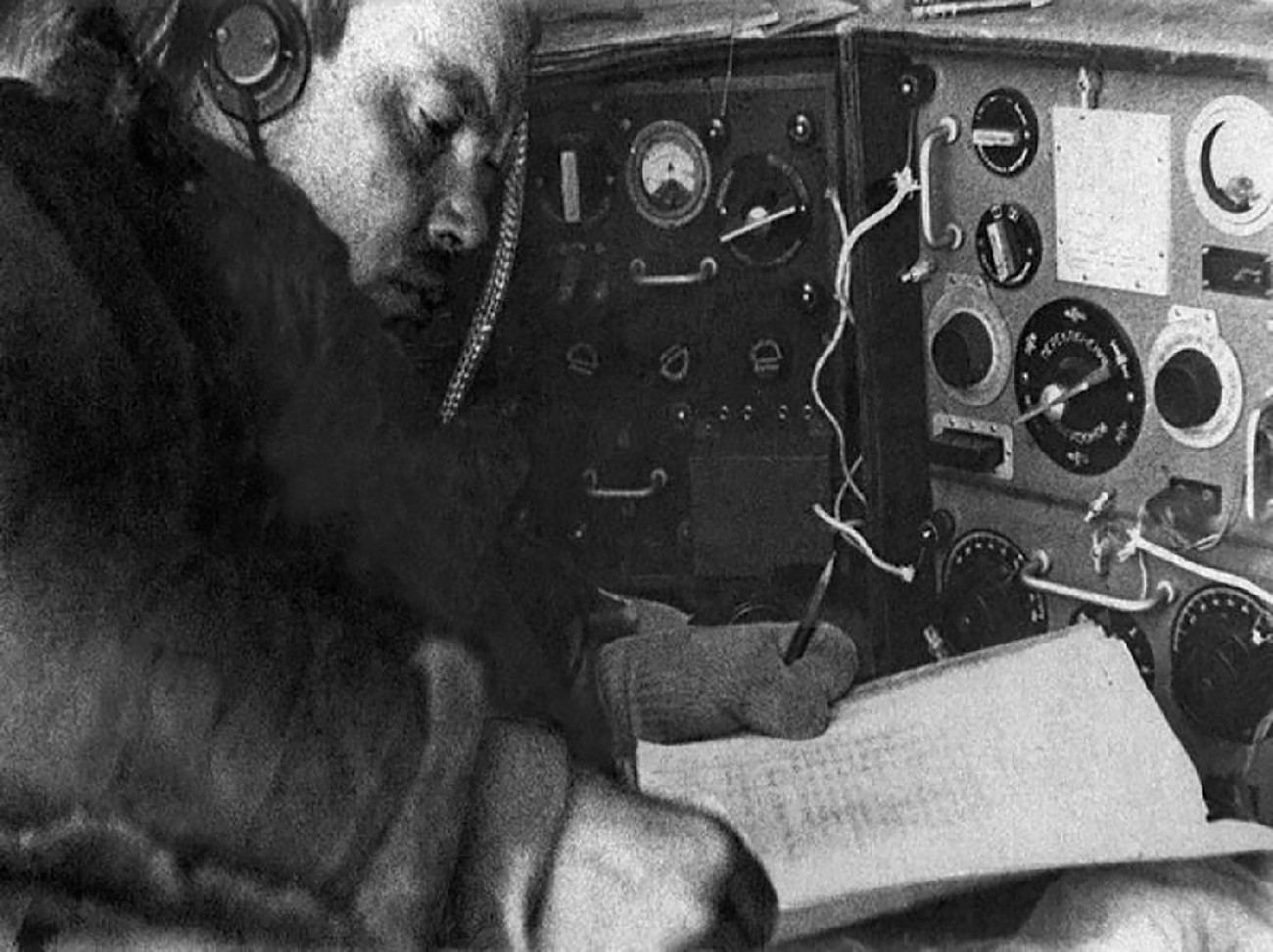

In addition to scientific reports, station radio operator Ernst Krenkel broadcast a stream of details for the Soviet press about life aboard the most incredible expedition in the world. During these popular radio marathons, he made contact with an amateur radio enthusiast from southern Australia and a sailor from the Hawaiian Islands, who were also closely monitoring the trials and tribulations of the polar explorers.

In September, the approaching Arctic winter made itself felt. The sun sank ever lower, cloaking everything in near-permanent twilight; the temperature no longer rose above zero and heavy snowfalls arrived. “The wind was so strong, it knocked you off your feet. It was impossible to leave the tent to gulp some fresh air. Inside, it was at once very stuffy and cold. My head was spinning,” Papanin recalled.

As it moved south toward the Greenland Sea, the ice floe began to crack and pieces broke off. The explorers listened fearfully at night as the ground literally opened up beneath them. “We are surrounded by cracks and large channels. If the floe collapses during the blizzard, it will be difficult to escape... The sleds and kayaks are covered with snow. Getting to the food bases is unthinkable...” Papanin noted in his diary on Jan. 29.

Following an almost week-long storm in early February, the ice under the station was torn apart by cracks 1.5–5 meters wide. The utility warehouse was flooded, the maintenance depot got cut off, and a crack appeared directly beneath the tent. “We’ll move to the snow house. I’ll report the coordinates later today; if communication is lost, don’t be concerned,” the radio operator reported to the mainland.

On Feb. 19, 1938, a few dozen kilometers off the coast of Greenland, two Soviet icebreakers Taimyr and Murman rescued the scientists from what remained of the once huge ice island. The world’s first drifting polar station was now situated atop a tiny ice floe 300 meters long and 200 meters wide.

Over the course of 274 days, the polar explorers had drifted more than 1,500 miles on the ice floe. Greeted as heroes back home, they soon became officially recognized as such. For their outstanding feat in the field of Arctic exploration, station chief Ivan Papanin, meteorologist and geophysicist Evgeny Fedorov, radio operator Ernst Krenkel, and hydrobiologist and oceanographer Pyotr Shirshov were awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. The first drifting station North Pole-1 was followed by another 30 such Soviet expeditions. And modern-day Russia continues to organize them on a regular basis.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox