5 Russian leaders with physical abnormalities

Boris Yeltsin and Gerhard Schroeder

Wolfgang Kumm/dpa/Global Look PressInformation on the physical abnormalities of the people who ruled Russia has always been meticulously concealed and kept secret – for security reasons. Both internal and external enemies of the state could easily use such information in dangerous ways. Also, Russian people of the past firmly believed that the tsar was a unique human being, an emissary of God, so if the people knew the tsar or the leader had any disfigurements, it became fertile soil for gossip, misinformation, and even panic.

Some leaders, however, couldn’t conceal their physical deformities. The founder of the Moscow state, Vasily Vasilyevich of Moscow, was blind (blinded, to be precise), while Boris Yeltsin, the first President of Russia, was visibly missing two fingers.

1. Vasily II of Moscow – blindness

Vasily II of Moscow. This portrait is just a picture from a chronicle. We don't have any images of Vasily and don't know how he looked like.

Public domainVasily Vasilyevich (1415-1462) was the first Prince who ascended to the princely throne of the Grand Duchy of Vladimir (the most powerful Russian feudal state of the early 15th century) not in Vladimir, but in Moscow, a relatively young city at the time. From his reign Moscow became the principal Russian city – so we can consider Vasily II of Moscow the founder of the Moscow state. During his time, a fierce feudal war was being waged, and Vasily was blinded during this war, earning the moniker “the Blind.”

Blinding was an old Byzantine way of taking revenge upon or neutralizing one’s enemy in a feudal war. In 1436, Vasily II himself ordered his servants to poke out the eye of Vasiliy Yuryevich (1421-1448), Prince of Zvenigorod. After that, Vasiliy Yuryevich became known as Vasiliy Kosoy (the Squint). He was maimed because he betrayed Vasily II of Moscow and tried to attack his army out of the blue.

Vasily II was blinded by agents of Dmitry Shemyaka (?-1453), Vasiliy Yuryevich’s younger brother who was taking his revenge. Dmitry persuaded two other Russian Princes – Ivan of Mozhaysk (?-1485) and Boris of Tver (1398-1461) to aid him against Vasily II of Moscow. Dmitry lied to them that Vasily was going to ‘sell’ the Moscow Rus to Ulugh Muhammad (1405–1445), the Khan of Kazan. Vasily had recently bailed himself out of the Kazan Khan’s prison, taking over 200,000 rubles (in times when 50 rubles were a fortune that could buy you a middle-class city house) from the Moscow treasury and giving annual tributes from several Russian cities to the Kazan Khan.

That's how probably the cities of the Feudal Rus' looked before and during Vasily's times. "The Defense of a City From Khan Tokhtamysh, 14th century" by Apollinary Vasnetsov (1856-1933).

Apollinary VasnetsovIn February 1446, while Vasily II and his two sons (aged five and six) were on a pilgrimage to the Trinity Sergius Lavra near Moscow, the conspirator princes took the Moscow Kremlin and took Vasily’s wife and mother as prisoners. Immediately, thugs were sent to the Trinity Lavra and they brought Vasily II to Moscow in chains.

Dmitry Shemyaka was afraid of simply murdering Vasily II. It could cause an even more disastrous war among the Russian princes and the Khan of Kazan could use this moment of disunity as a chance to attack Rus’ again. Dmitry, however, thought for two full days before ordering Vasiliy II blinded. A kind of public trial was organized, where princes Vasily, Ivan, and Boris ‘interrogated’ Vasily II of Moscow, asking him: “Why did you bring the Tatars to Moscow land and give them contributions from Russian towns?” On the morning of February 17, 1446, Vasily II’s eyes were put out.

Russian chronicles say that that night, Shemyaka’s men went to the room in his house where Vasily II was being held. They jumped on him, knocked him down, and pressed him to the floor with a board to his chest. Then, a stableman named Beresten’ blinded Vasily II using a knife, wounding his face heavily in the process. After completing the ghoulish work, they left, leaving Vasily passed out in a pool of his own blood.

Shemyaka became the Moscow Prince, and Vasily II was exiled to Uglich. His wife was allowed to accompany him. Soon, however, the relentless Vasily regained his spirits. He returned to the Moscow throne by eliminating his enemies. Dmitry Shemyaka was poisoned by his cook (bribed by Vasily’s people). After eating a poisoned chicken, he suffered for 12 days before dying. Vasily II the Blind wore a black eyepatch covering the upper part of his eyeless face.

2. Peter the Great – Marfan syndrome (hypothetical)

The sculptured head of Peter the Great made after his death mask is probably the only reliable image of the Emperor.

shakko (CC BY-SA 3.0)Peter the Great (1672-1725) was 6ft 6 inches tall. Both his parents were a little taller than average. But Peter’s unnatural lankiness turned heads from his youngest days. As an adult, he stood two heads over any crowd. But he wasn’t sturdy built, had narrow shoulders, and his shoe size was US 7 (EU 40, UK 6.5).

Peter the Great's Hessian boots

Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikNot a single popular portrait of Peter reflects his real stature. His overly long arms and legs, and a small head were many times described by the contemporaries. Hypothetically, Peter could have had Marfan syndrome – a genetic disorder of the connective tissue. As medics confirm, people with Marfan tend to be tall and thin, with long arms, legs, fingers, and toes. They also typically have flexible joints and scoliosis, a sideways curvature of the spine.

One of the few paintings trying to capture the real stature of Peter the Great and the speed of his movement. "Peter I", 1907, by Valentin Serov (1865-1911).

Valentin SerovPeter was known to be obsessively active. As a kid, he couldn’t bear to sit on the Moscow tsar’s throne for hours during the court ceremonies. As an adult, he did everything very fast, even ate and walked fast, and kept himself busy almost all the time.

As for scoliosis, there are numerous records of Peter often stooping and hunching his head to the side. Also known in people with Marfan syndrome is an anterior chest wall deformity (pectus excavatum), and Peter’s original frock coat we see was tailored for a person with a remarkably long and thin chest.

Peter the Great's ceremonial kaftan (a kind of jacket)

Hermitage MuseumPeople with Marfan syndrome often are in an excited or irritated state. Peter was known to have suffered seizures, grimacing, tilting his head, twitching his arms and shoulders. Juel Just, the Danish envoy to Russia, wrote that “this happened often when he was angry, received bad news, upset or deep in thought.” People with this syndrome are also known to be highly intelligent – we don’t have to remind you that Peter’s intellectual abilities were monstrous. Geniuses like Niccolò Paganini and Abraham Lincoln also, supposedly, had Marfan syndrome. Again, this is just a hypothesis – but it’s no doubt that Peter had abnormalities, not injuries, but of a genetic nature.

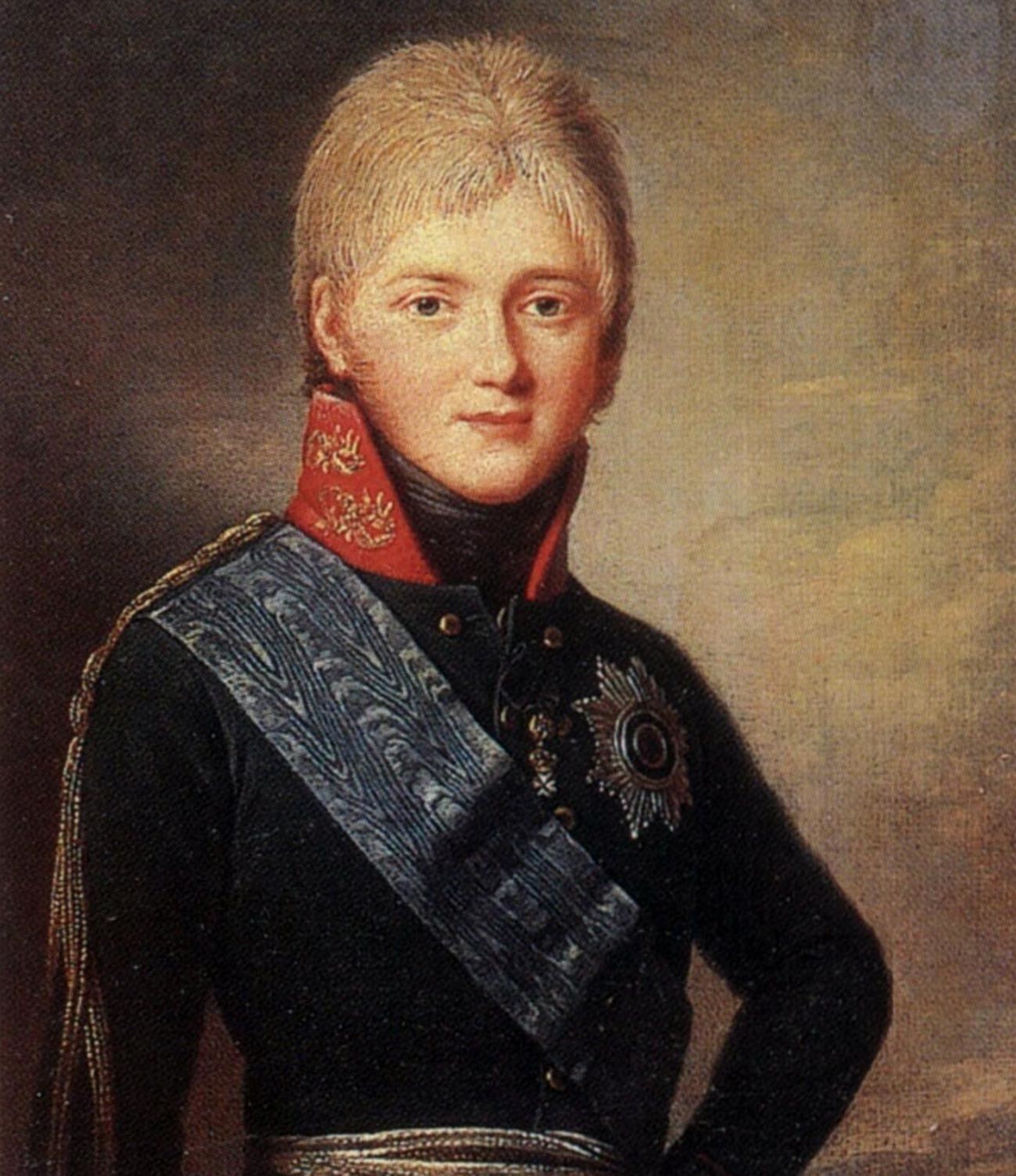

3. Alexander I – deafness

Grand Duke Alexander Pavlovich (the future Emperor Alexander I)

Public domainGrand Prince Alexander (1777-1825), son of Pavel I (1754-1801), was the grandson of Catherine the Great, who planned a stellar future for the boy. Almost immediately after birth, Catherine took the baby from his mother and raised him herself at her court. Even the boy's name was chosen by his paternal grandmother.

Peter III, Catherine’s husband, murdered in 1762, was afraid of cannon shots even as an adult. On one hand, this was mighty strange for a nobleman who was raised partly in military training, on the other hand… quite explicable – the guy was just afraid of cannons from the very start. This was the subject of clandestine mockery and secret jokes of the entire Russian Imperial Court. Catherine, who had troubles in her family life with Peter, detested his infantile behavior and his playing toy soldiers all the time.

Emperor Alexander I by Franz Krüger (1797-1857)

Franz KrügerThat’s why she probably wanted her grandson to be a real man, accustomed to cannon fire. Russian historians are sure this was the reason for Alexander’s famous deafness: he was totally deaf in one ear, and heard with difficulty in the other. As early as 1794, Alexander Protasov, the Grand Prince’s mentor, wrote that his student was deaf, but refused to admit it and cure it.

Alas, if the reason for his deafness was cannon fire (such assumptions were made already during his lifetime), then his eardrum could have burst, and this couldn’t be cured in the 19th century. When talking to people, Alexander instinctively leaned his head and turned his right side to his interlocutor. He also spoke very quietly, in order ‘not to seem deaf.’

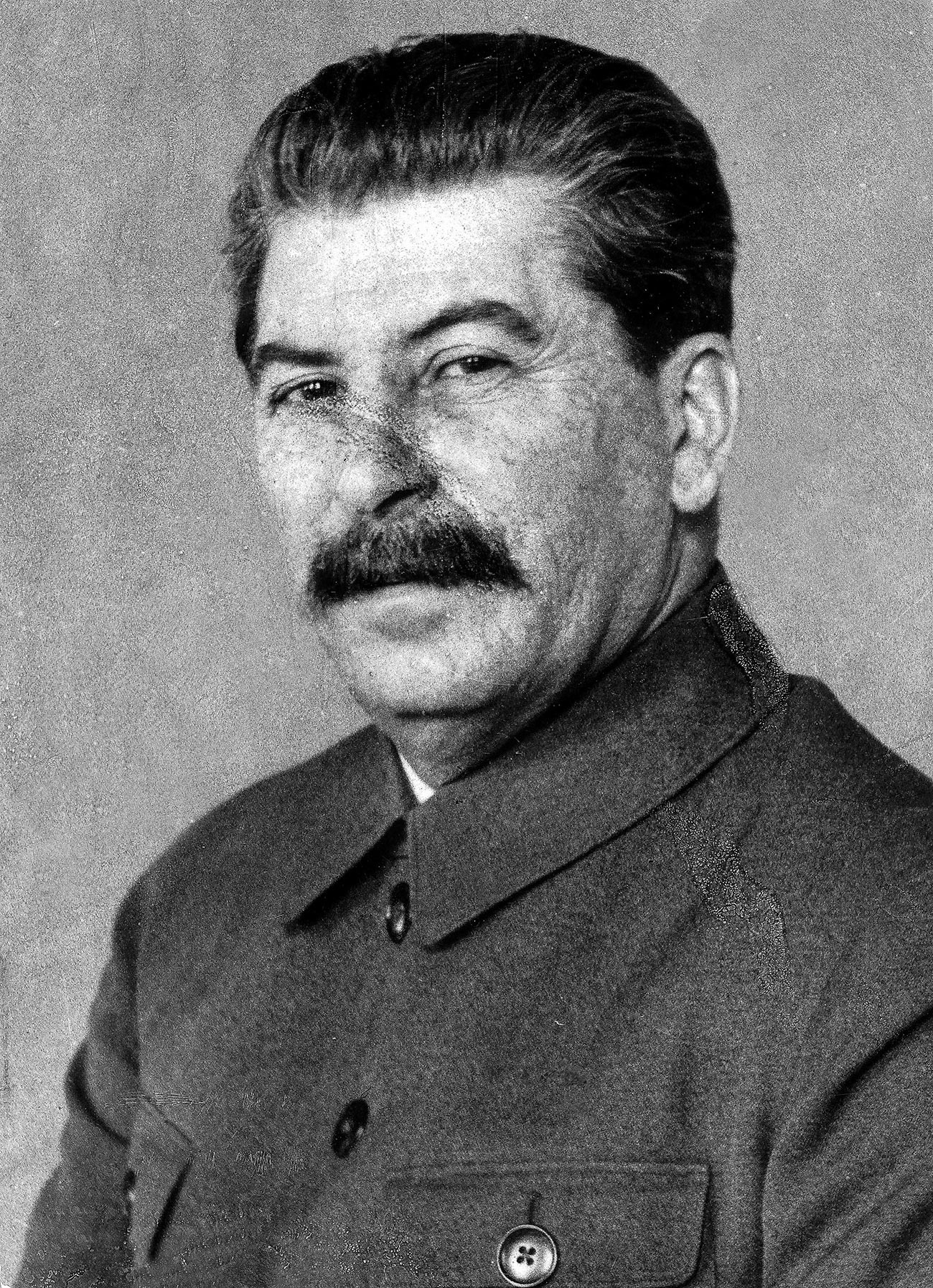

4. Joseph Stalin – fused fingers, muscle atrophy

This is one of the rare photos of Stalin where pockmarking is obvious on his face.

Getty ImagesJoseph Stalin really had something to hide. He had syndactyly – his second and third toes were fused. At the age of five, Stalin suffered smallpox, causing extensive pockmarking over his face – and hours of meticulous work for retouchers who edited the General Secretary’s photos for newspaper publications.

Vyacheslav Molotov in his book of interviews “140 conversations with Molotov” remembered Stalin telling him that in 1913 while he was in exile in the Turukhansk District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, the villagers there nicknamed him Os’ka (diminutive for Iosif) the Rough – because of the pockmarks and maybe because he had a lame left arm.

At the age of six Stalin was hit by a phaeton - a light open carriage - while crossing the street. He suffered severe injuries in his left arm and his head. After this, his left arm was only half as strong as his right one and he couldn’t properly lift it or hold it straight. With age, he also started feeling constant itching and pain in the fingers of his left hand.

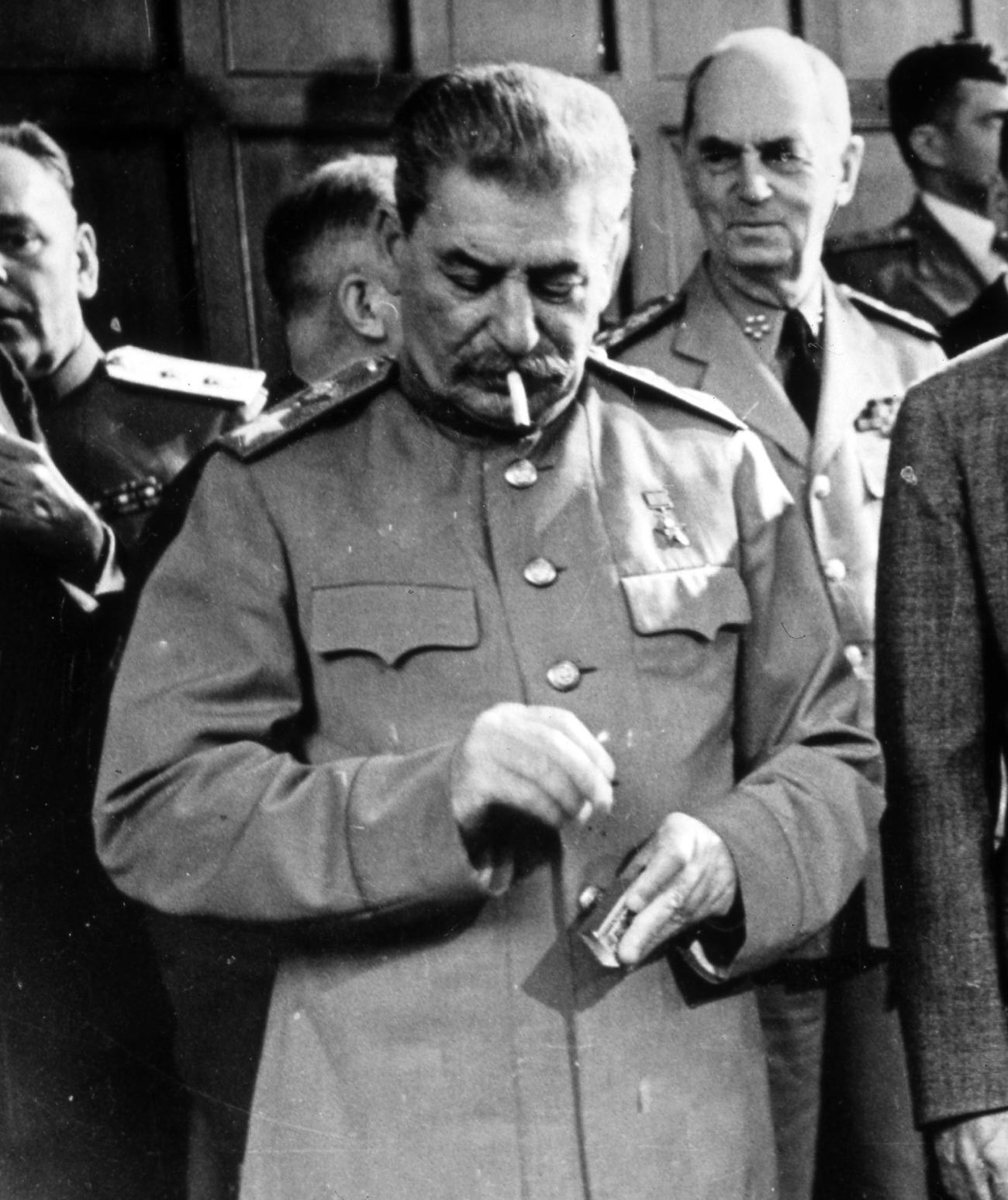

Joseph Stalin lifting his daughter Svetlana up with his both arms

Public domainKremlin doctors characterized his disease: “Atrophy of the shoulder and elbow joints of the left arm as a result of a bruise suffered at the age of six, with further suppuration in the area of the elbow joint.” However, in various photos of Stalin we see he can control his arm quite well – he could even lift a child, for example, his daughter in this photo.

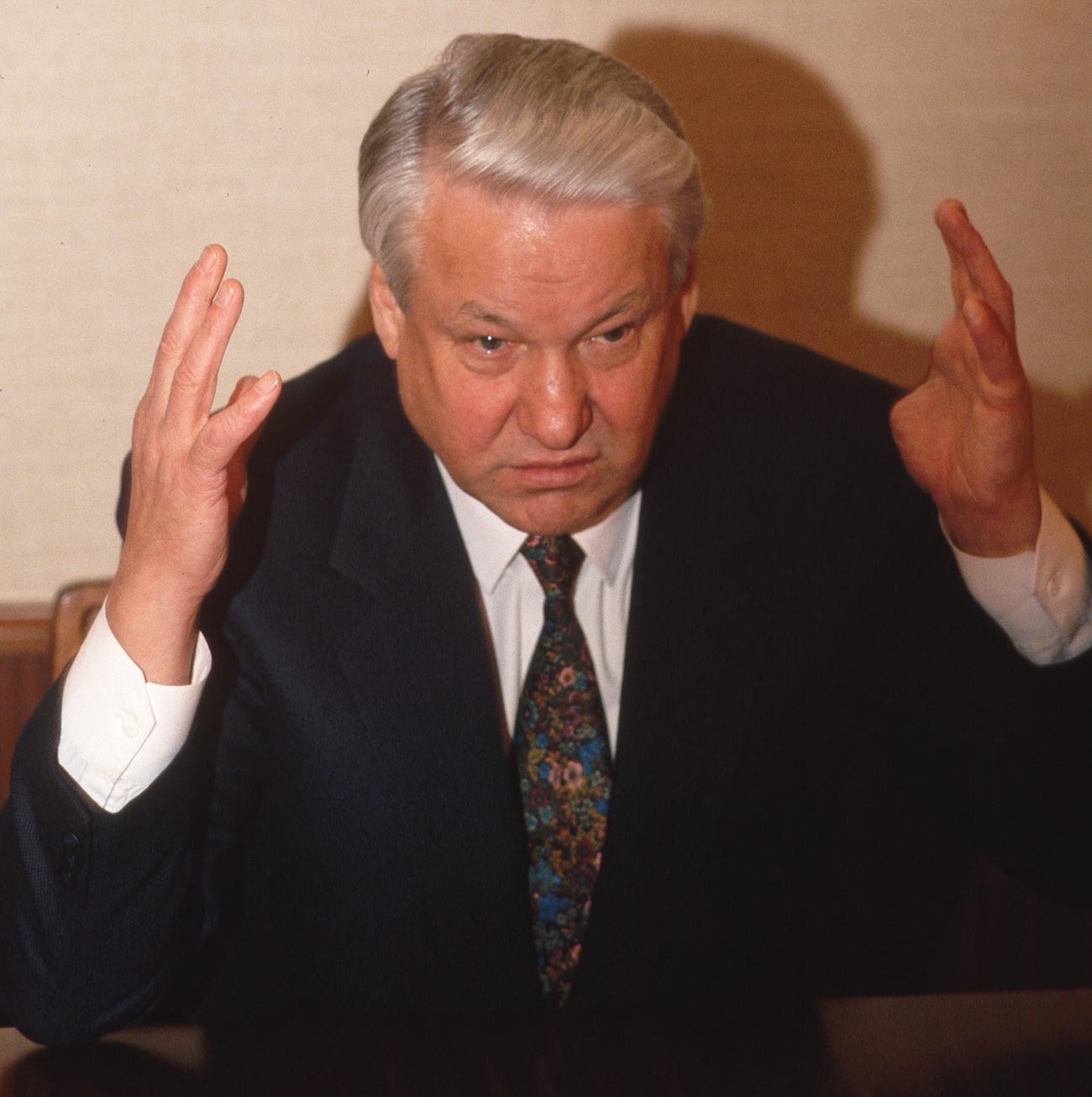

5. Boris Yeltsin – two missing fingers

Boris Yeltsin (1931-2007), the first President of the Russian Federation, lost two fingers when he was a teenager. There’s no mystery to how it happened: Yeltsin wrote about it in his autobiography “Confession on a Given Theme” (1990).

“During the war (Yeltsin was 10 at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945), all the lads wanted to go to the front lines, but nobody let us, obviously. We made guns, rifles, even a cannon. We decided to procure some grenades and dismantle them, to study and understand what’s inside. So I volunteered to sneak inside the church (where the military warehouse was). After dark, I sneaked through three barbed wire perimeters and, while the sentry was at the other side of the building, I hand sawed the bars over a window. Got inside, took two RGD-33 hand grenades and got away safely. I was lucky – the sentry would have shot without warning.

Boris Yeltsin during an interview

Getty ImagesWe went to the forest, 60 kilometers away from there, and started dismantling the grenades. I persuaded the guys to get a hundred meters away, and hit it with a hammer, standing on my knees. The grenade was lying on a rock. But I didn’t know I had to take out the fuse first. Explosion… fingers gone. The guys were safe. During the ride back to town, I passed out several times. At the hospital, with my father’s written consent (gangrene started in my hand), I was operated on, cut off what was remaining of the fingers, and I appeared in school with a bandaged, white hand.”

Boris Yeltsin didn’t serve in the army because of the injury. All his life, he was embarrassed about his left hand and preferred poses that helped him hide it. Vladimir Sokovnin’s portrait of Yeltsin captures one of his favorite stances with his injured hand hidden.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox