How 'Russian samurai' fought for Japan in World War II

The Bolsheviks’ victory in the Russian Civil War forced hundreds of thousands of Russians to flee the country. However, they, as well as their children, did not stop hoping that, one day, they would return to their homeland and overthrow the Soviet regime they hated so much.

If, in their struggle against the USSR, many Russian emigres in Europe sided with Hitler, those who had settled in the Far East chose the Japanese Empire as their ally.

Allies

The Japanese had started forging ties with White Army emigres living in Manchuria in northeast China in the 1920s. When in 1931 the Kwantung Army occupied that region, a significant part of its Russian inhabitants supported the Japanese in the fight against the Chinese troops.

A puppet state, Manchukuo, was set up on the territory of Manchuria and Inner Mongolia, headed by the last Chinese emperor, Puyi. However, real power there belonged to the Japanese advisers and the leadership of the Kwantung Army.

The Japanese and Russians there found common ground in their hatred of communism. They needed each other in the upcoming “liberation” war against the Soviet Union.

‘Russian samurai’

Under the official ideology of Manchukuo, Russians were one of the five ‘indigenous’ peoples of the state and enjoyed equal rights with the Japanese, Chinese, Mongols and Koreans living here.

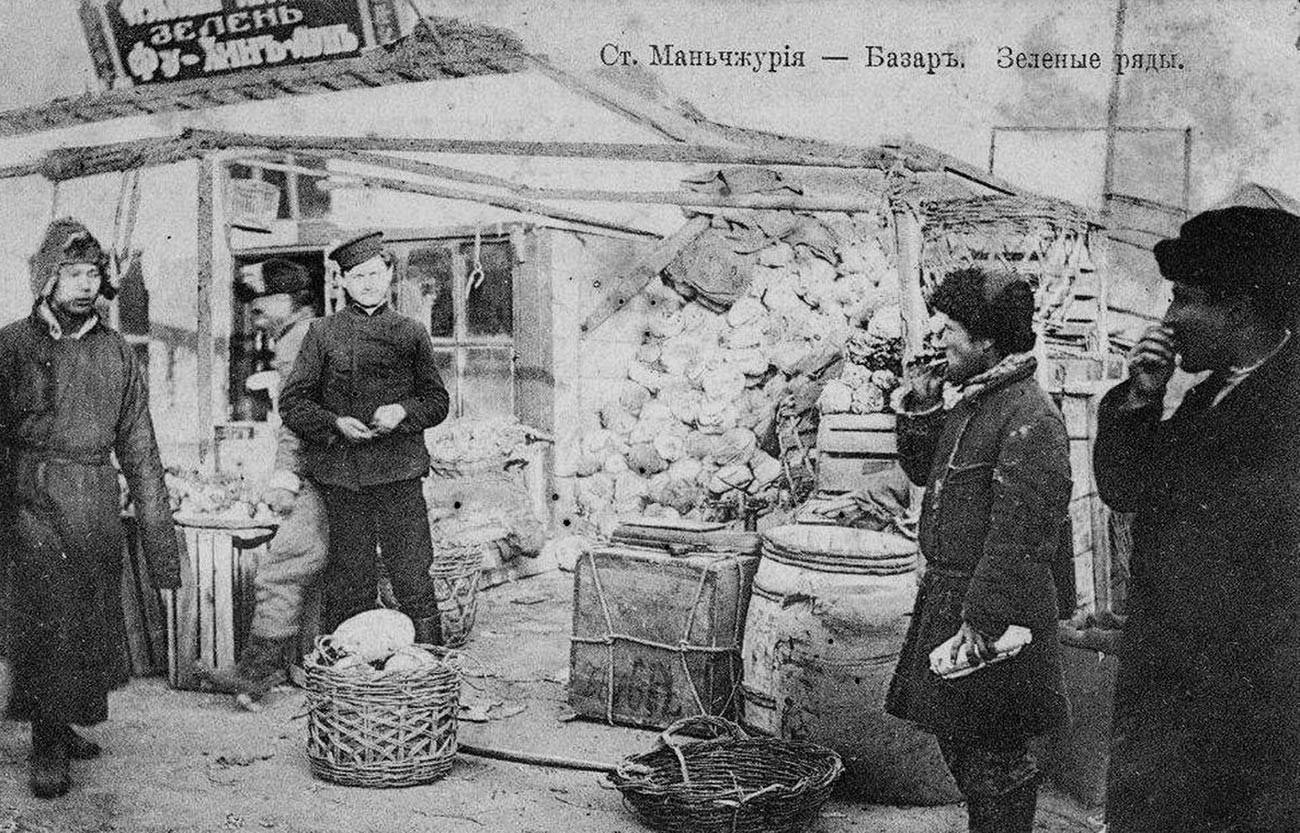

Japanese troops entering Chinchow.

World War II databaseAs a sign of their favorable attitude towards White Russian emigres, the Japanese actively involved them in cooperation with their intelligence bureau in Manchuria, the Japanese military mission in Harbin. Its head, Michitarō Komatsubara, noted once about the Russians: “They are ready for any material sacrifice and gladly take on any dangerous enterprise in order to destroy communism.”

In addition, numerous Russian military detachments were set up to protect key transport facilities from attacks by local honghuzi bandits. Later, they would also be used to fight against Chinese and Korean partisans.

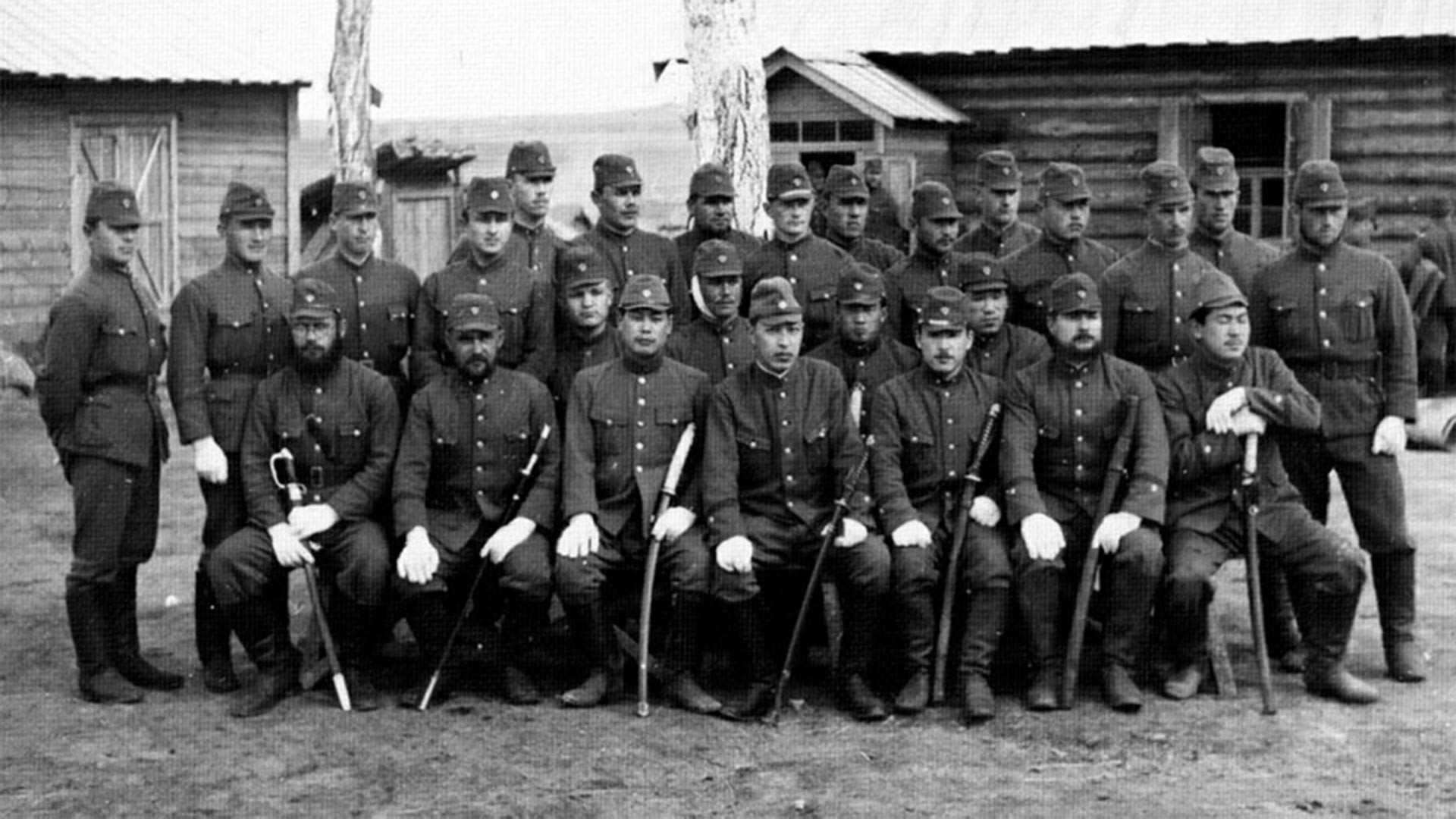

The ‘Russian samurai’, as General Genzo Yanagita called White Army emigres who collaborated with the Japanese, received both military and ideological training. On the whole, their attitude towards the idea of creating Greater East Asia under Japan was neutral, bordering on positive, although they were far less enthusiastic about the plan to seize all Russian lands up to the Urals, which, however, they had to carefully hide.

“We filtered what the lecturers stuffed us with and discarded the superfluous, Nippon spirit that was at odds with our Russian spirit,” one cadet by the name of Golubenko recalled.

Asano detachment

The most prominent among the Russian military units created by the Japanese was the ‘Asano’ detachment, named after its commander Major Asano Makoto. At different times, it numbered from 400 to 3,500 people.

Founded on the birthday of Emperor Hirohito, April 29, 1938, the detachment comprised infantry, cavalry and artillery units. Based in Manchukuo, Asano’s soldiers were nevertheless fully supervised by the Japanese military.

Fighters from that secret unit were preparing to carry out sabotage and reconnaissance operations on the territory of the Soviet Far East in a future war against the USSR. In it, their task would be to capture or destroy bridges and important communications nodes, to infiltrate into Soviet units and poison kitchens and water sources there.

The Japanese Empire tested the military potential of the Red Army twice, in 1938, near Lake Khasan, and in 1939, on the Khalkhin Gol River. Fighters from the Asano detachment took part in both those operations, although their function mainly consisted in questioning Soviet prisoners of war.

That said, there were also reports that they were involved in real clashes with the enemy, too. Thus, during the battles on Khalkhin Gol, a cavalry detachment of the Mongolian People’s Republic came across Asano’s cavalrymen and took them for their own. That mistake cost most of the Mongolian soldiers their lives.

A new role

By the end of 1941, the Japanese leadership had abandoned its plan of a blitzkrieg against the USSR, known as the Kantokuen plan. And by 1943, it was clear that there would be no Japanese invasion of the Soviet Far East in any shape or form.

As a result, the Japanese carried out a reform of their Russian detachments, turning them from special-purpose sabotage and reconnaissance into ordinary combined-arms units. Thus, the Asano detachment, which had lost its secret status, became part of the 162nd Rifle Regiment of the Armed Forces of Manchukuo.

Nevertheless, Tokyo continued to value its Russian soldiers highly. In May 1944, the younger brother of Emperor Hirohito, Prince Mikasa Takahito, paid a visit to where Asano’s fighters were based. In his address to the soldiers, he spoke of strengthening the morale and military training of the Japanese and Russian peoples.

Defeat

The difficult and heroic struggle of the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany resulted in a surge of patriotism and anti-Japanese sentiments among the Russian population of Manchuria. Many officers began to collaborate with Soviet intelligence. As it turned out, even one of the leaders of the Asano detachment, Gurgen Nagolyan, was an NKVD (Soviet secret police) agent.

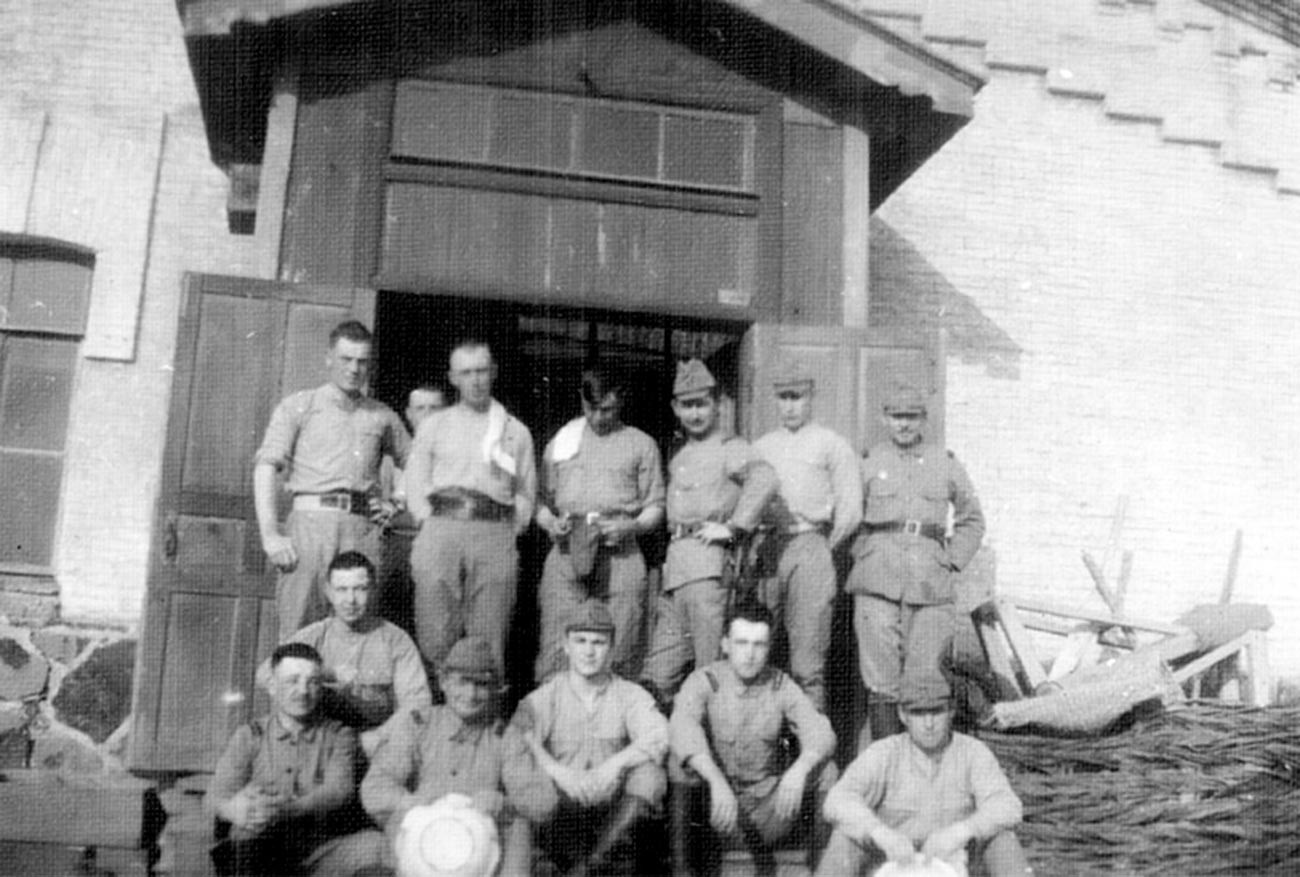

When on August 9, 1945, the Red Army invaded Manchuria, local Russian military units reacted differently. A small part of them put up armed resistance, but were quickly crushed along with the Manchukuo troops. Soviet Major Pyotr Melnikov recalled that from the Japanese side there often came shouts in Russian aimed to confuse and disorient the Soviet soldiers, trying to figure out who was friend and who was foe.

Most of the Russians, however, decided to change sides. They arrested their Japanese commanders, set up guerilla detachments to fight the Japanese, and, having taken control of settlements, handed them over to the advancing Soviet troops. Occasionally, Red Army soldiers even became friends with White Russian emigres, and the latter were entrusted with carrying out guard duty at some facilities.

However, the idyll ended when, following the Soviet military units, SMERSH counter-intelligence officers arrived. Moscow, which had a wide intelligence network in Manchuria, was well aware of the activities of local White Army emigres over the previous years. They were taken to the USSR en masse, where the more senior figures were executed, while the others were sentenced to up to 15 years in Gulag camps.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox