The story behind the failed Palace of the Soviets

The Palace of the Soviets, a modern reconstruction of the 1930s model

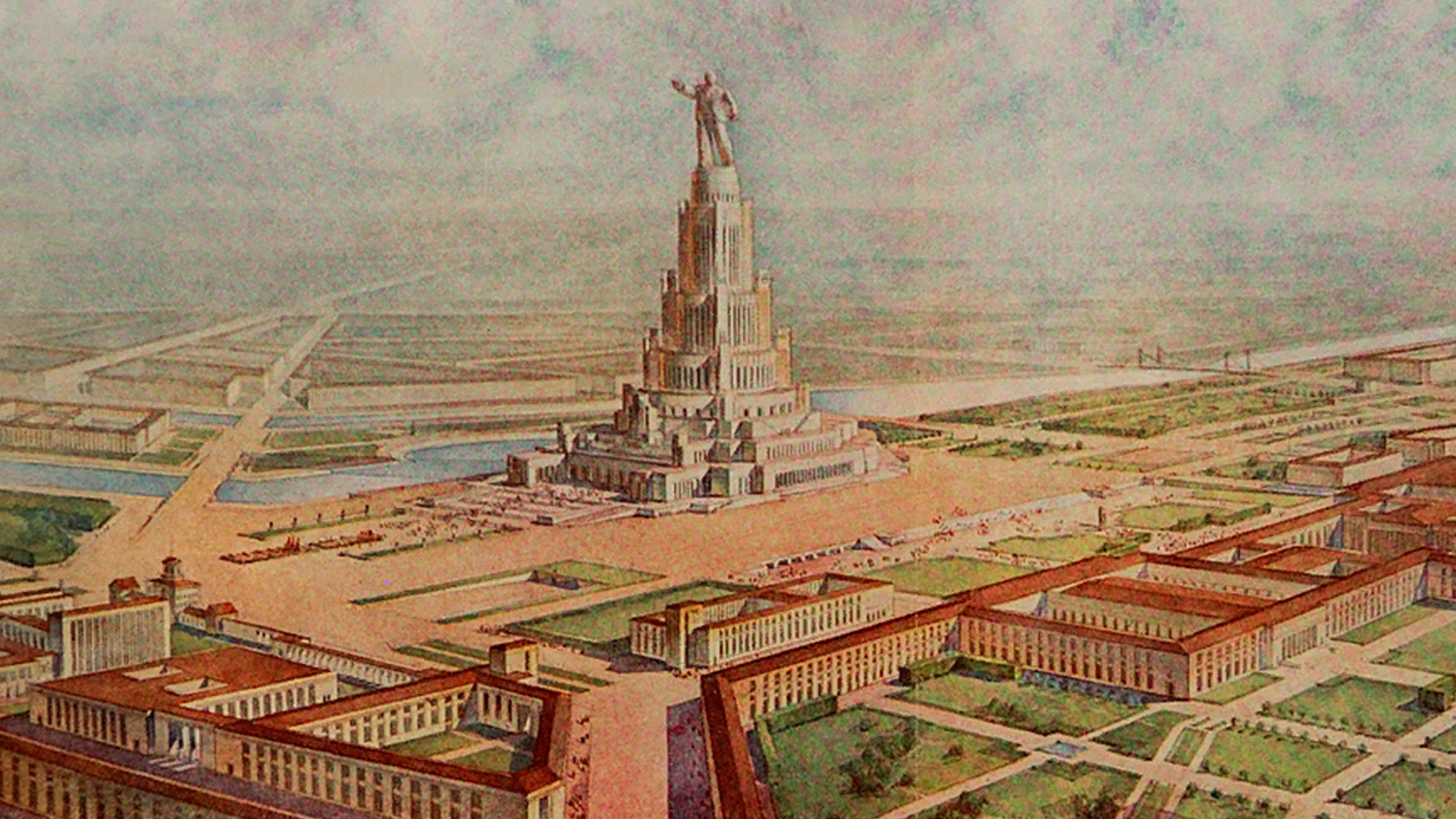

Ilya IlyusenkoThe Palace of the Soviets is the most famous and grandiose of the unrealized projects of the Soviet government. Conceived in the early 1920s, it was supposed to become the main building and a symbol of the new country. The plan was that it would house government bodies, serve as a venue for sessions of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR and mass demonstrations, and even have a swimming pool inside.

A giant reaching to the sky

Illustration for the Palace of the Soviets

N.S. Atarov/Moskovsky Rabochy [Moscow Worker] magazine, 1940Apart from its symbolic meaning, the Palace of the Soviets had another, no less important value: it was supposed to become an architectural manifesto of the Soviet regime, which by the early 1930s had already turned away from the ideas of constructivism in search of a new big style. The winner of an international competition for designing the giant building was a team of Soviet architects led by Boris Iofan, the author of the famous House on the Embankment (an apartment block not far from the Kremlin where senior government and party figures lived). To the end of his days, the architect regretted that the main project of his life was never realized.

A 100 meter statue of Lenin instead of a worker

A model of the Palace

Boris Iofan, Vladimir Gelfreykh, Vladimir ShchukoIn Iofan's design, the Palace of the Soviets was to become the tallest building in the world at the time (its total height was to be 495 meters/1625 feet!) and symbolize the victory of socialism. In the original version, the building was to be crowned with a statue “The Free Proletarian”, an 18 meter/60ft-tall figure of a worker with a torch in his hand. As was often the case at the time, Stalin personally intervened in the design work, pointing out that the palace should become a monument to Lenin and his teaching - and the statue of the proletarian was replaced by an almost 100 meter statue of Lenin.

A model of the Palace from Moscow Museum archive

Mikhail Filimonov/Sputnik“The arm of the statue stretching over Moscow will have a length of almost 30 meters. The index finger is over four meters long. On a clear sunny day, the Lenin statue will be visible from a distance of tens of kilometers,” the design documents said.

It was projected that the palace would be able to accommodate up to 40,000 people at a time. The main entrance, facing the Kremlin, was to be decorated with statues of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Architecturally, this monumental structure, generously decorated with bas-reliefs depicting Soviet symbols, was meant to mark a transition from the avant-garde to the Stalinist Empire style.

From a conference room to a swimming pool

A hall of the Civil Glory

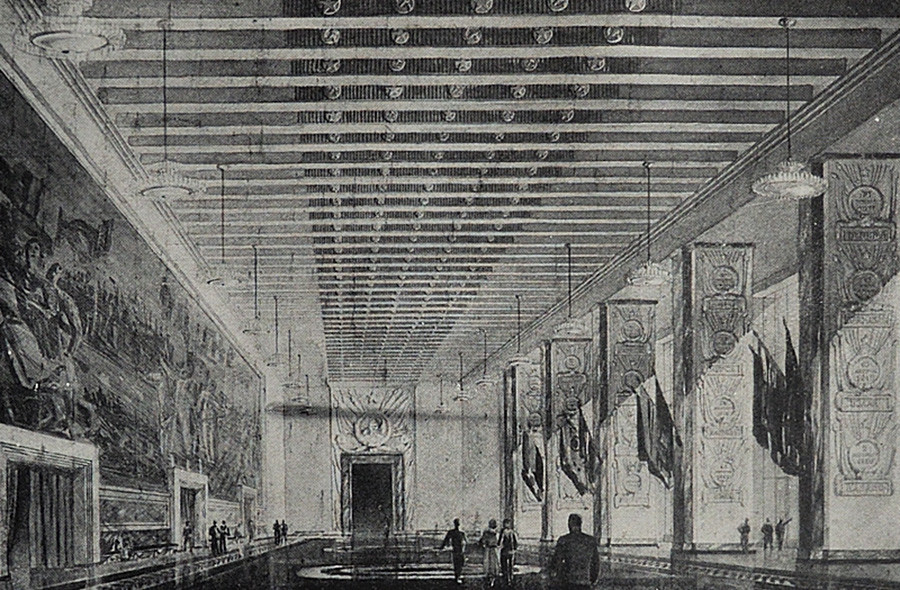

N.S. Atarov/Moskovsky Rabochy [Moscow Worker] magazine, 1940The Palace of the Soviets was conceived as one of the most technologically advanced buildings in the world. It was to have high-speed elevators, air purification systems, multi-function halls with giant media screens. One of its novel ideas was a stage which, if necessary, could turn into ... a swimming pool.

Major redesign of the center of Moscow

The General plan of Moscow reconstruction. The Palace of the Soviets is marked with 5

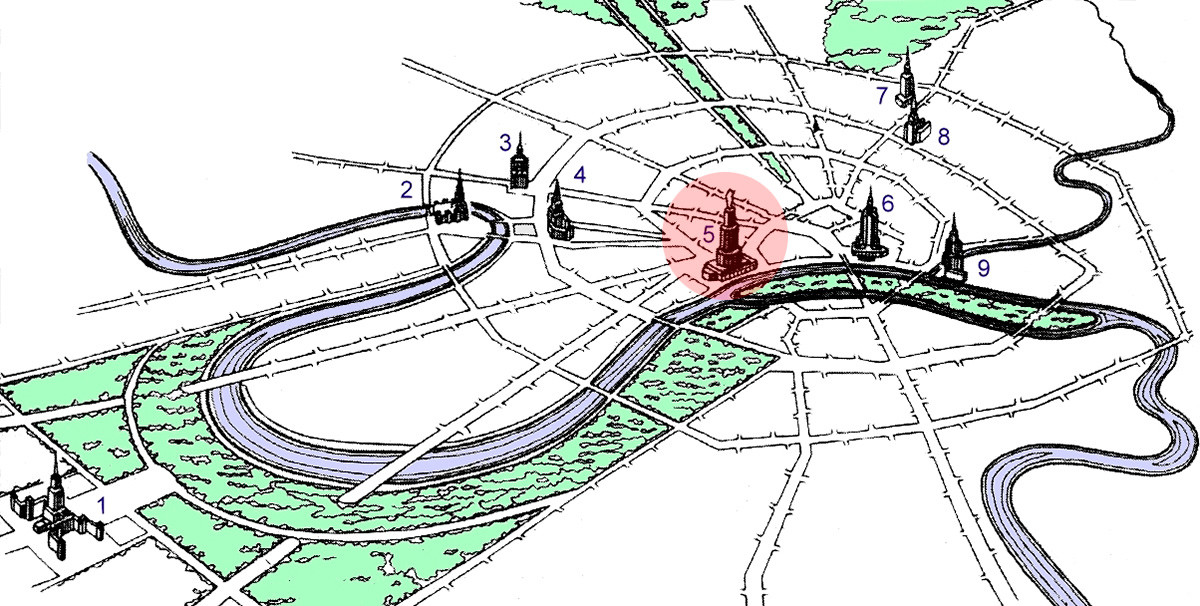

Union of Soviet architectsThe Palace of the Soviets was supposed to be built near the Kremlin, on the site of Christ the Savior Cathedral. From it, an Avenue of the Palace of the Soviets was to be laid all the way to Lubyanka Square, with roads radiating from it to link different parts of the city to the center. To this end, all pre-1917 buildings in the city center were to be demolished, with the exception of several particularly valuable ones, like the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Volkhonka, which, however, would have to be moved in order to allow for the planned road expansion. These grandiose plans were cut short by World War II.

A swimming pool instead of a palace

Moskva swimming pool, 1977

Ivan Denisenko/SputnikIn 1931, the Cathedral of Christ the Savior was blown up and the foundation for the new building began to be laid. The work lasted eight years and after the outbreak of World War II, was suspended altogether. In 1941-1942, the metal frame of the palace was dismantled, with the resulting material used to build bridges and anti-tank barriers. After the war, the project was never resumed. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was not a fan of it. In 1960, the largest swimming pool in the USSR (130 meters/425ft in diameter), called Moskva, was built on the site where the foundation of the palace once was. The all-season open-air swimming pool outlived the Soviet regime: it was closed only in 1994 to make space for the restored Cathedral of Christ the Savior.

The project's short-lived resurrection after Stalin's death

A still from 'The New Moscow'

Alexander Medvedkin/Mosfilm, 1938After Stalin's death, the idea of building the palace was resurrected only once: in 1956-1958, a new competition for the best architectural project was held. This time however, the building was planned to be located not in the city center, but in the southwest of Moscow, not far from Moscow State University. However, these plans were soon abandoned as the country was entering a period in its history known as the Thaw and was on the verge of another urban planning revolution. Thus, the Stalinist Empire style with its monumentality and huge budgets forever became a thing of the past.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox