How the Soviets fought against the Americans in Vietnam (PHOTOS)

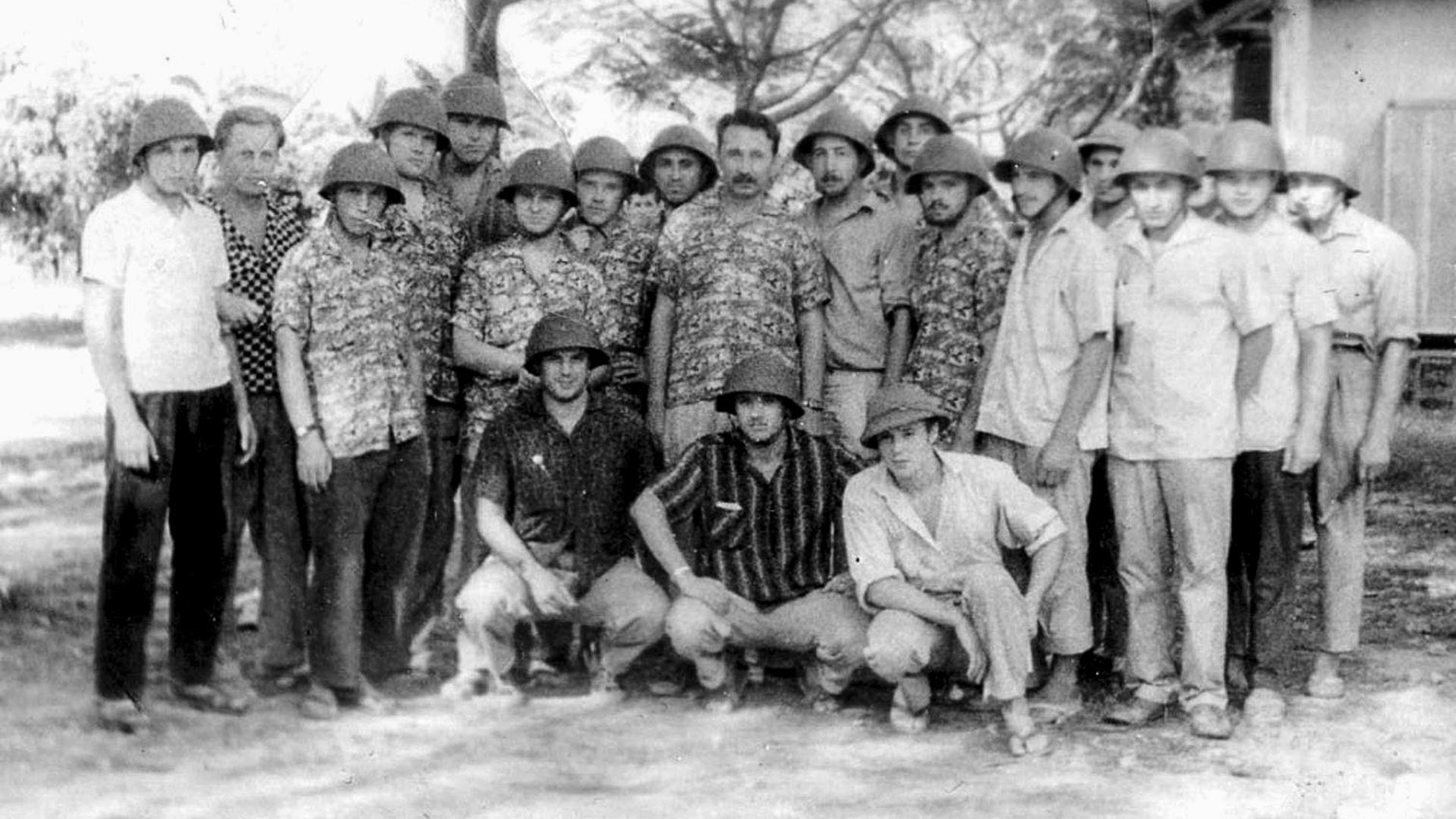

Soviet military specialists in Vietnam, 1965.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarThe Soviet Union could not stand by and watch indifferently as the Americans were carrying out their intervention in Indochina. In April 1965, just a month after the United States had started sustained aerial bombardment of North Vietnam, known as ‘Operation Rolling Thunder’, the first Soviet air defense missile systems and military specialists servicing them began arriving in the country, at the request of the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

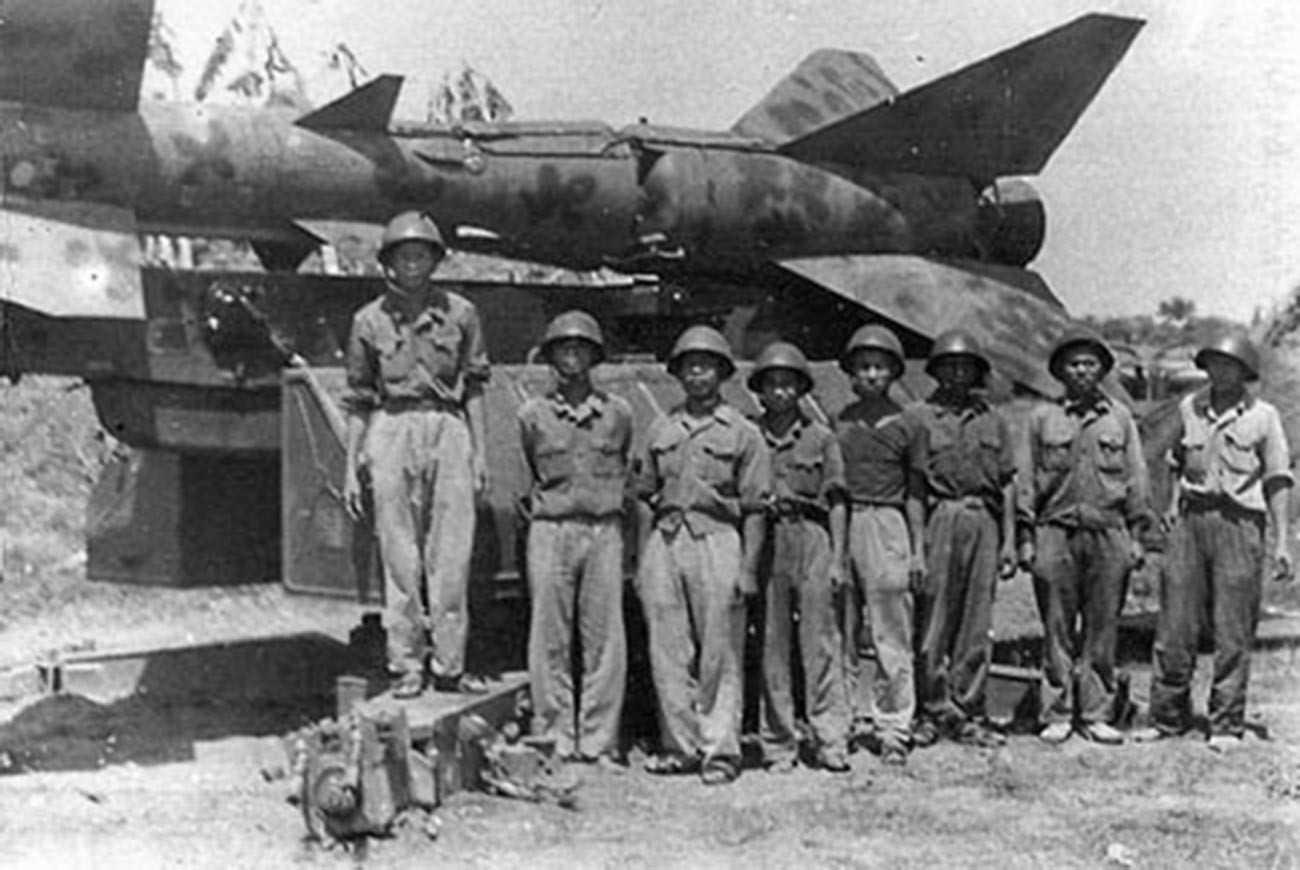

Vietnamese People's Army soldiers stand near the anti-aircraft missile, that protects the city against the U.S. Air Force raids.

Lev Porter/TASSThroughout the war, Moscow provided Hanoi with 95 S-75 air defense missile systems, over 500 airplanes, 120 helicopters, more than 5,000 anti-aircraft guns and 2,000 tanks. In addition, more than 10,000 Soviet military specialists were dispatched to Vietnam: from missile crews, pilots and signalmen to tank crews and doctors.

Soviet military equipment in Hanoi.

A.Guryanov/SputnikA special role was also played by Soviet anti-aircraft gunners. They not only trained Vietnamese People’s Army (VPA) personnel, but also took part in fighting themselves. It is in no small degree thanks to them that the U.S. Air Force and Navy, having lost more than 4,000 aircraft, failed to suppress North Vietnam's air defenses and defeat the country.

Anti-aircraft training center in Vietnam, 1965.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarRim Kazakov, a guidance systems officer with the 274th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “To give credit to our Vietnamese comrades, they successfully mastered the weaponry entrusted to them and were always by our side. In addition to taking part in actual combat with missile crews, we - having learnt some basic Vietnamese - regularly conducted training using simulation equipment. We overcame the psychological barrier of the first launches together: I pushed the ‘Start’ button and the Vietnamese guidance systems officer only pushed it already after the launch, sometimes probably not even suspecting it.”

Colonel Evgeny Antonov with his Vietnamese colleagues, 1970.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarGrigory Belov, in September 1965 - October 1967, commander of the Group of Soviet military specialists in Vietnam: “While assisting the Vietnamese in fighting, we just told them: Do like us, i.e. study and master military equipment and weapons as well as we know them, perform your duties with exactness and precision like us, shoot like us. However, when it came to person-to-person relations, things were a bit more complicated. The Vietnamese, be it military or civilian personnel, were watching and studying us, trying to understand what our motives and goals were in being there - after all, it was just a little over 10 years since the French had been expelled from Vietnam. It was only when they realized that we were assisting them not out of mercenary interests, but from the heart, not sparing ourselves, that all we wished to the Vietnamese people was to defeat the aggressor, they began to treat us with deep respect, and I would say, with love.”

VPA servicemen, 1967.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarGennady Shelomytov, a firing battery commander with the 274th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “For a month, we were at the controls ourselves, while the Vietnamese, by sitting next to us and observing our actions, gained experience of conducting combat firing. Then, they moved to the controls, while we stood behind them, controlling their actions. This lasted for three to four months. As the Vietnamese gained combat experience, our military specialists began to return home in small groups... We were constantly on the move. Positions changed very often - after each live firing. Positions detected by American pilots were invariably subjected to massive bombing the next day or sometimes literally in a couple of hours. So staying in the same place was very dangerous.”

Vietnamese anti-aircraft gunners and Soviet military specialists.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarAnatoly Zayika, head of a Group of Soviet military specialists attached to the 238th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “That was a dramatic and difficult battle. First, the battalion came under fire from American aircraft. The missile system was seriously damaged. It seemed the battalion was put out of action for a long time. A second group of enemy aircraft aimed to deliver a second, final and devastating strike. But our men did not flinch - they restored the missile system to working order and met the second air raid with fire. They destroyed two carrier-based attack aircraft. Hooray! The most difficult victory is the first one, but it is a hundred times dearer than an easy one.”

A U.S. military aircraft shot down in Vietnam.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarMajor Igor Korbach, from an essay about Colonel Nikolay Beregovoy: “In the course of fighting, we came up with the idea of ambushes. Battalions secretly, usually at night, took up positions along the probable flight routes of enemy aircraft. Ambushes were set up far from guarded facilities. Battalions went deep into the jungle, to the border with Laos. They made two or three launches, shot down one or two planes and immediately left the position.”

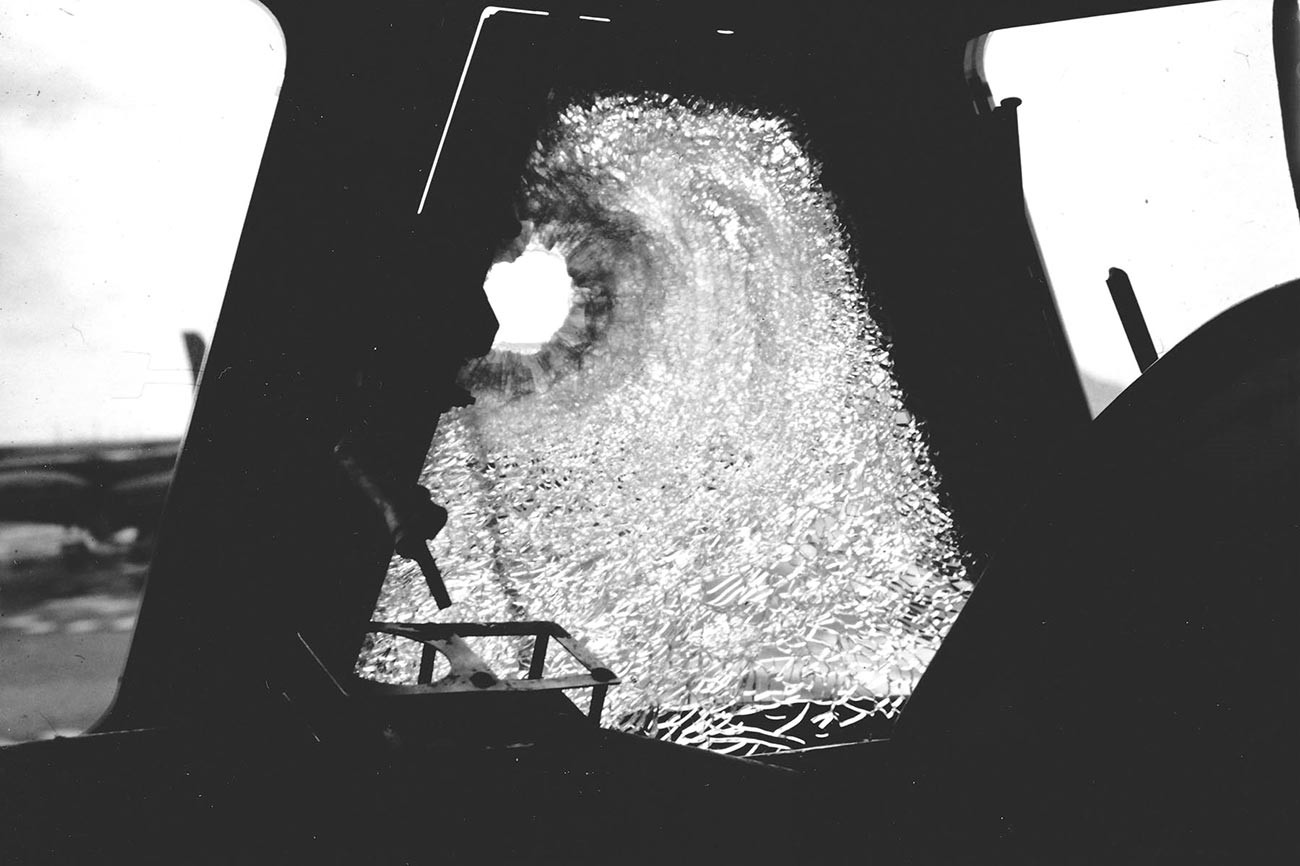

Boeing B-52 pilot’s window damaged by a fragment from an SA-2.

National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceLyubov Roslyakova, a staffer at the headquarters of the commander of the Group of Soviet military specialists in Vietnam: “One summer day, there was such an air raid that remembering it even now fills me with dread. A pellet bomb hit the corner of the building housing employees of the staff of our military attache... The explosion was so big that a deep crater formed where the corner of the building used to stand, and the wall of the building was riddled with holes from the pellets. Buildings nearby and those opposite were also damaged. Fortunately, everyone was at work at the time, so no-one was killed. After the air raid, we entered a room in the building next door (where our medical center was based) and saw that there, too, the walls, which were probably 40 cm thick, were riddled with holes from the pellets, which were everywhere, on the bed, on the table and on the floor...”

An F-4B Phantom II of Fighter Squadron VF-111 Sundowners drops 227 kg Mk 82 bombs over Vietnam during 1971.

U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval AviationBoris Voronov, chief of staff of the Group of Soviet military specialists from May 1967 to April 1969: “Temperature in the shade reached 40C degrees above zero, and it was very humid. Cabins in the missile guidance station had no air conditioners, so the fans inside were just pushing hot air around and did nothing to cool either the equipment or the military personnel working there. Our servicemen's uniform consisted of a steel helmet and underpants. Sweat just streamed down their bodies to the floor. There were never-drying puddles of sweat under operators' seats in the cabins. There were cases of severe heat rash when people were no longer able to fight and had to be taken to hospital.”

Soviet military specialists and Vietnamese anti-aircraft gunners, 1967.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarAlexander Anosov, assigned to a special mission in Vietnam as part of a group of military science experts: “The group was selecting and studying seized American weapons and hardware: unexploded ordnance, mines and what remained of downed American aircraft. Since during the Vietnam War, the Americans lost over 4,000 aircraft, there was a lot of work to do and we were never idle. These days, our group is sometimes unflatteringly described as trophy collectors, but back then, in Vietnam, we were known more as a ‘Wild Division’. Although, in fact, we were nothing near a division. We were just a handful of people, but something happened to us all the time: something would explode, or catch fire, etc. The funny thing was that we were ‘based’ in a small room in our embassy building in Hanoi, and all our ‘adventures’ were in plain sight. So when we - dirty, tired and unshaven – returned with trophies from yet another field trip, people would give us a wide berth, just in case.”

Soviet specialists examine the fragments of the B-52 Stratofortress near Hanoi, 1972.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarSenior lieutenant Vadim Shcherbakov, a guidance systems officer with the 88th Battalion in the 274 Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “My confrontation was not with an aircraft, but with its pilot... Peering into the indicators on the control console, it felt as if I was looking into his face, breathing into the back of his head, feeling his every movement, feeling inside me what he was doing now in his sealed cabin, flying over the green carpet of the jungle, and waited. I waited for his nerves to snap or for his impudent self-confidence to prevail. And when that happened, that was it! I’ve gotcha! Launch! And... see you on the ground (if you are lucky enough to eject from the downed plane and if the first people to come across you are a U.S. rescue team rather than a group of Vietnamese peasants armed with hoes... I wish you luck...). Nothing personal. Today is just not your day. Or maybe it is not mine...”

An F-105 hit by the Soviet S-75 "Dvina" missile.

National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceNikolay Kolesnik, a launching station commander, a deputy platoon commander of a firing battery in the 236th and then the 285th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiments of the VPA: “All the interpreters were VPA officers, and a lot depended on their position in resolving some issues. That is why the interpreters were important and respected people in the regiment. Their opinion was taken into account by our and by the Vietnamese commanders alike. In addition to purely technical translation difficulties, they had to independently resolve numerous organizational matters arising in the training process, and later – issues of coordination and interaction between the regiment’s battalions and other services, and they put all their skill and strengths into this complex work.”

Military drills in Vietnam.

Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam WarVyacheslav Kanayev, commander of the 1st battery of the 1st battalion of the 5th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “One night, the battalion was alerted to an approaching target. The conditions were perfect for a successful launch: the target was flying at an optimal altitude (6 km) and at low speed, yet that was exactly what put Alexander Gladyshev (the commander of the 1st battalion) on his guard. He did not give the order to open fire, and several seconds later it turned out that it was a Chinese-made mail plane that did not have an IFF transponder. The commander’s intuition and experience saved the aircraft and its crew.”

VPA anti-aircraft gunners.

Valentin Sobolev/TASSTauno Pyattoyev, head of a Group of Soviet military specialists attached to the 236th and 275th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiments of the VPA: “The Vietnamese constantly warned us of the danger of an enemy attack on the ground (telling us not to go anywhere unprotected or alone, especially when working on combat positions). On the morning of December 25, a platoon observation post of the 67th battalion spotted three groups of paratroopers being dropped with parachutes further down along road No. 20. So the threat of an attack was real and potential attackers would obviously not be amateurs. And how could we, Soviet military specialists, oppose them? We did not have any small arms or any papers.”

An AC-130 plane of the US Air Force on the runway in Kbam Bleh, Vietnam, 1966.

Consolidated US air Force/Global Look PressAlexey Belov, head of a Group of Soviet military specialists attached to the 278th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “One clear day, a RA-5C Vigilante carrier-based reconnaissance aircraft flew above our dugout at an altitude of about 100 meters. The group was working with the 92nd battalion, while I was writing a report. I went outside to stretch my legs and at that moment I met the gaze of the pilot flying the reconnaissance aircraft. That night we changed our location, and the following day, five high-explosive bombs and five pellet bombs were dropped on the houses that we had just left.”

Mk 84 bomb explosion Vietnam.

Public domainYuri Demchenko, commander of a firing battery of 82nd battalion in the 238th Surface-to-Air Missile Regiment of the VPA: “At that moment, suddenly, from the other side – from the west – there came a sound like an approaching thunder, followed a few seconds later by three powerful explosions behind the cabin. I turned in that direction and saw two black clouds rising from our tents, my missile from launcher No. 1 flying up in the air and immediately exploding, and three American planes making a left turn. Seconds later, there came a burst of gunshot and several more explosions, and our diesel engines immediately went quiet. I saw soldiers and officers jumping out of the cabins and running towards the nearest shelter. Someone pushed me there, too. Soon, warrant officer Nikolayenko walked in carrying in his arms a Vietnamese diesel engine mechanic wounded in the chest, then firing battery commander Corporal Martynchuk, who had been wounded in the shoulder, ran into the shelter, too. Suddenly, everything went very quiet and I jumped out of the shelter. The first thing I saw was the burning camouflage of the cabins, and a missile tank compartment on fire on launcher No. 6. Launcher No. 1, from which the missile had been blown away by a blast wave, was in its initial position, while the other five launchers, cut off from power, froze motionless facing in the same direction.”

Vietnamese soldier watching explosion during the Vietnam War.

Getty ImagesEduard Lekanov, commander of a platoon of Volkhov surface-to-air missile launchers: “In July 1966, we were stationed near Hanoi, guarding the largest bridge in Southeast Asia. At the battery next to us, a Vietnamese crew was entrusted with carrying out a launch independently, but both their missiles missed the target. The Phantom turned around to attack. A napalm bomb exploded near our battery, and a few drops hit my thigh. I must have automatically put out the burning mixture streaming down my leg with soil. Immediately a đồng chí (meaning “comrade” in Vietnamese) ran up to me and treated the wound. In our battery, I was the only one wounded, while the crew that fired and missed were all killed. After that incident, the Vietnamese were for a long time suspended from carrying out independent launches: ‘Military science must be learned properly!’”

A U.S. Air Force SAM Hunter killer group of the 388th Tactical Fighter Wing takes fuel on the way to North Vietnam for a strike during "Operation Linebacker" in October 1972.

National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceVladimir Balakin, a radar operator at the Ampermet small reconnaissance ship, who took part in voyages to the combat zone of the U.S. Air Force and Navy in the Pacific Ocean: “There were one or two helicopter carriers of the U.S. Navy stationed off the coast of South Vietnam. We reported their whereabouts, recording communications both between the ships and between pilots and the base. There were other semi-military and civilian ships in our field of vision. When Soviet ships carrying weapons, equipment and food entered North Vietnam ports, American pilots, as a rule, bombed not them, but Vietnamese junks that carried the cargo from the Soviet ships to the shore. I can recall only one instance when the Americans dropped a shot shell from an airplane, which pierced the deck and board of a Soviet ship below the waterline. Having hurriedly patched the hole, the ship quickly unloaded its cargo and left for repairs.”

USS Abnaki (ATF-96) and Soviet trawler Gidrofon underway in the South China Sea, 1967.

Naval History and Heritage CommandRussia Beyond would like to thank the Inter-regional Public Organisation of Veterans of the Vietnam War (MOOVVV) and its board chairman Nikolay Nikolayevich Kolesnik for the provided materials.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox