Tsarist Russia’s top cop

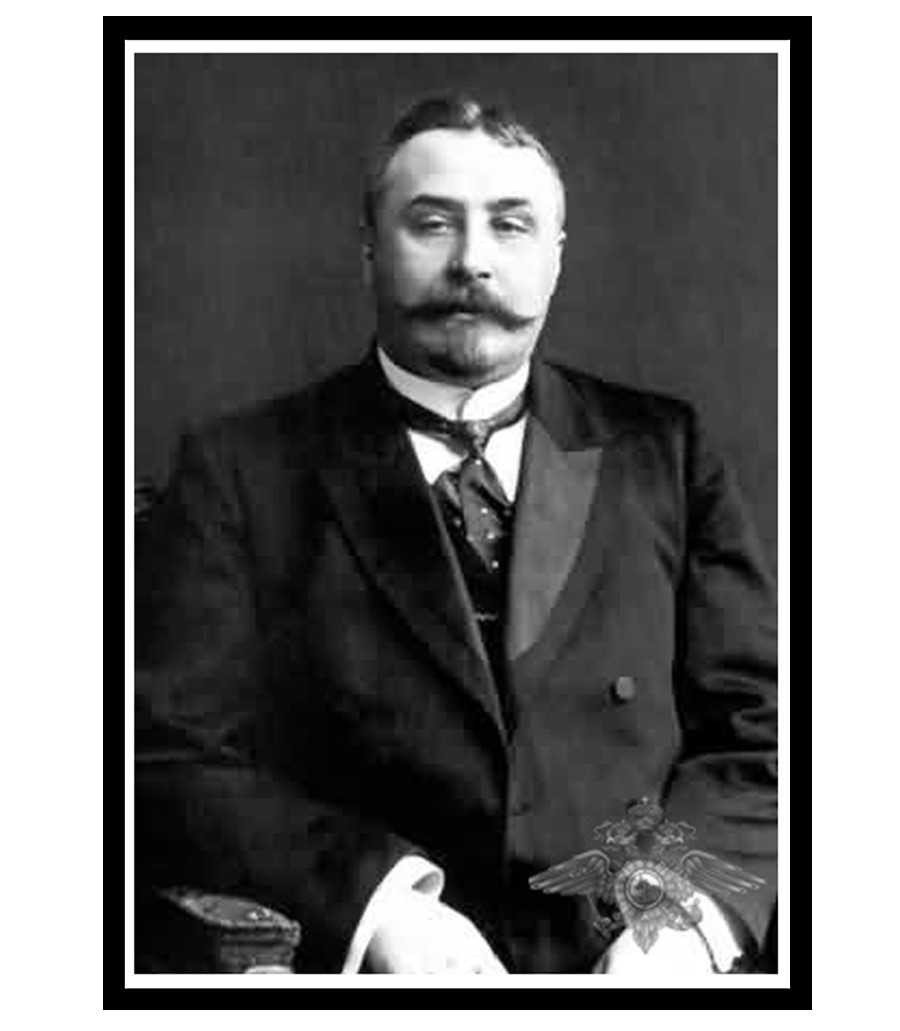

Arkadiy Kohsko

Russia Beyond, archive photoShooting for his childhood dream

Arkadiy Koshko was born in 1867 in the village of Brozhka, Minsk Province. The future lead investigator of the Russian Empire came from a noble, wealthy family, with roots in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. His surname, originally, was Koshka, with the ‘a’ gradually becoming an ‘o’ in the years that followed.

Arkadiy Koshko

Archive photoOwing to his noble beginnings, Arkadiy Frantsevich decided to follow in his family’s footsteps by joining the military. His large family all supported his chosen career path, unaware that his heart desired a different one. Since early childhood, Koshko had found inspiration in crime novels, picturing himself in the role of an investigator. This dream was put on hold by his studies at the Kazan infantry cadet school, followed later by a move to Simbirsk (now Ulyanovsk).

His days there were dreary and monotonous. Koshko, being an active and energetic individual, was, frankly, bored with it all. In 1894, the young officer decided it was time to make a radical change and realize his childhood dream. He started by becoming a junior detective in Riga. The family was not pleased, but they could hardly do anything to stop him.

Koshko was satisfied with his chosen direction. He was now in the midst of the action. In his three years on the force in Riga, he managed to solve eight crimes, which was a huge accomplishment for those days. But it didn’t come easy. Arkadiy was creative in borrowing tricks from the detectives in the crime novels he’d read as a boy.

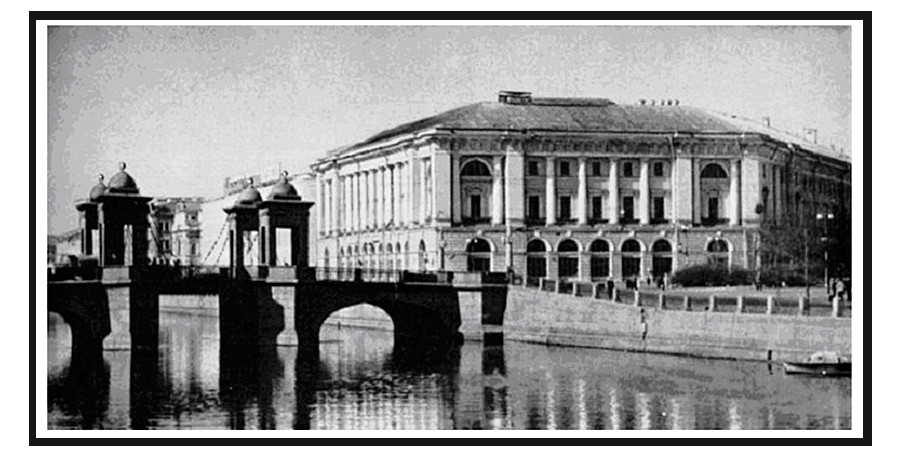

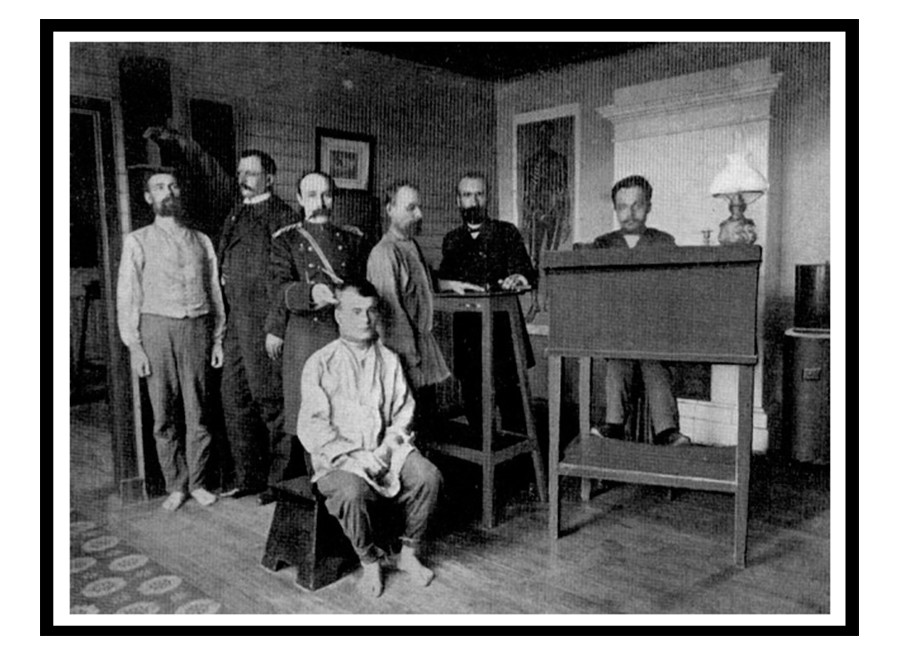

The office of the Criminal Investigation Force of the Russian Empire, St. Petersburg

Archive photoKoshko was a fan of ‘bait fishing’ as a method of luring out criminals. Makeup and costumes were indispensable to his line of work. He would often dress up and go undercover in some shifty Riga spot without backup. This way he managed to bring a band of card cheats to justice. Koshko took a few classes from the pros and managed to pass himself off as a player. He then overpowered several criminals and even managed to score a game with the gang’s leader. The arrest was performed during the game.

Koshko’s meteoric rise

The criminal situation in the Russian Empire had gotten steadily worse. The police force was undergoing change. In March of 1908, the Director of the Department of the Police Maksimilian Ivanovich issued an order to create the Criminal Investigation Department. In June that year, the State Duma discussed the proposed law “on the creation of the investigative department”. Former deputy prosecutor of the Odessa District Court Ludvig Lutz, who also chaired the commission, spoke at the session. He declared that “a rapid recent increase in criminal activity compels the government to implement special measures in the fight against criminals”.

Investigators at work

Archive photoLutz then proposed an increase in police funding and the institution of a professional oversight body. His hopes were answered. The law “on the creation of the investigative department” was approved by Nicholas II and ratified by the State Duma on July 6, 1908. Investigative departments soon sprouted up all across the country.

There were pros and cons to the law. One of the cons was that each branch would only have jurisdiction in its own province, which prohibited it from hunting criminals on any other territories. If the investigation had to cross provincial lines, the precinct would have to pass the baton to the neighboring province. This negatively impacted the speed at which crimes were solved. There were, however, also the pros - the main one being that separate sets of legislation began to exist in order to govern the police and the criminal process.

Koshko made good use of that development. He first completed the objective of becoming the division’s director for Riga, then was invited to the Russian capital. Koshko became assistant director of the St. Petersburg Investigative Police. Soon after, the detective ended up in Moscow, this time as the director of the Investigative Police.

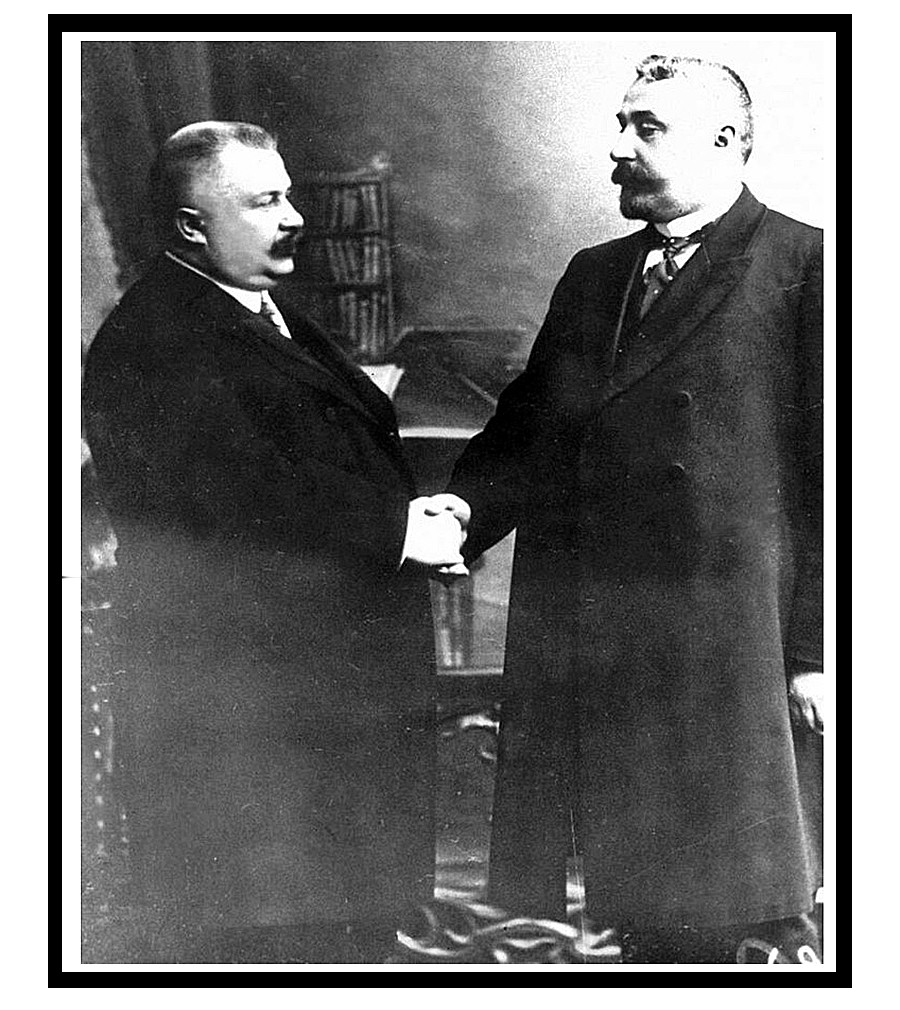

Arkadiy Koshko and the Chief of the St. Petersburg Criminal Investigation Police, Vladimir Filippov

Archive photoIn 1910, he managed to crack a case that had created a flurry of outrage in Moscow, including from the Russian Royal family. In spring, an evildoer robbed the Moscow Kremlin’s Assumption Cathedral. Upon inspecting the scene of the crime, Koshko suspected that the criminal might be hiding somewhere close by, having been spotted by a witness. Somewhere inside the cathedral. The police searched every nook and cranny, but found no trace of the suspect. Koshko then ordered the building to be surrounded, and for the police to simply wait. Finally, three days later, a young man emerged from behind the iconostasis. He was immediately arrested, which also led to the recovery of the precious icons of the Virgin of Vladimir. The criminal turned out to be a Sergey Semyonov, a jeweler’s apprentice. He had spent three days in the hideout, eating unleavened bread to stay alive, hoping the police would eventually give up.

The main case

The following year Koshko managed to neutralize the Vaska Belousov gang. The case could be considered to be among the biggest in his career. He would later write about it in his book, ‘The Criminal World of Tsarist Russia’.

The gang appeared suddenly in 1911. The thieves would mug wealthy people, but without causing bodily harm. Koshko joined the investigation when it became apparent the local police were getting nowhere. He soon arrested a member, who then gave up the leader during questioning. He added that the working class folk would defend Vaska Belousov with their lives, because he always gave to the poor. The police had a Moscow “Robin Hood” on their hands. It was clear why the investigation had stalled.

Belousov would often send the police letters, taking responsibility for the crimes: “The deed has been done by me, Vaska Belousov, the famous chieftain of an untouchable gang, born under the lucky star of Stenka Razin. Human blood I do not spill, but roam the streets I will. Do not hunt me - I can’t be caught. Neither fire, nor bullets could take me: I have been charmed.”

Criminal Investigation Police processing inmates, early 20th century

Archive photoVaska was carrying out so many crimes, however, that he gradually became careless and even spilled blood. Among the dead were police overseer Muratov. This directly led to Belousov being apprehended and sentenced to death. Arkadiy did not allow the hangman to execute him, however, taking the rope and saying: “Don’t mess it up, I’ll do everything.” And kicked the chair himself.

Police reform

Arkadiy Frantsevich always sought to apply the lessons he learned on the job. This quality prompted him to modernize the Moscow police in line with the new law: the position of detective-overseer was created, which implied a sort of internal affairs and coordination officer, who also handled detective work. Surveillance of the detectives was carried out by secret agents handpicked by Koshko. The system was later revealed to have a positive outcome. Not every mole or corrupt cop could be identified, but life became much more difficult for them.

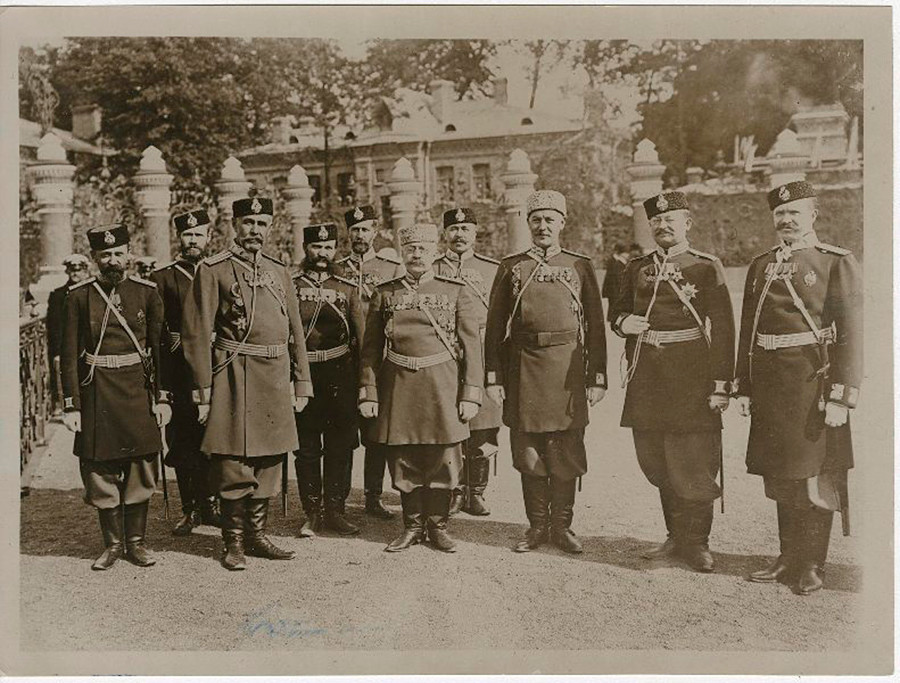

Policemen at the Mikhaylovsky Court, St. Petersburg, 1907.

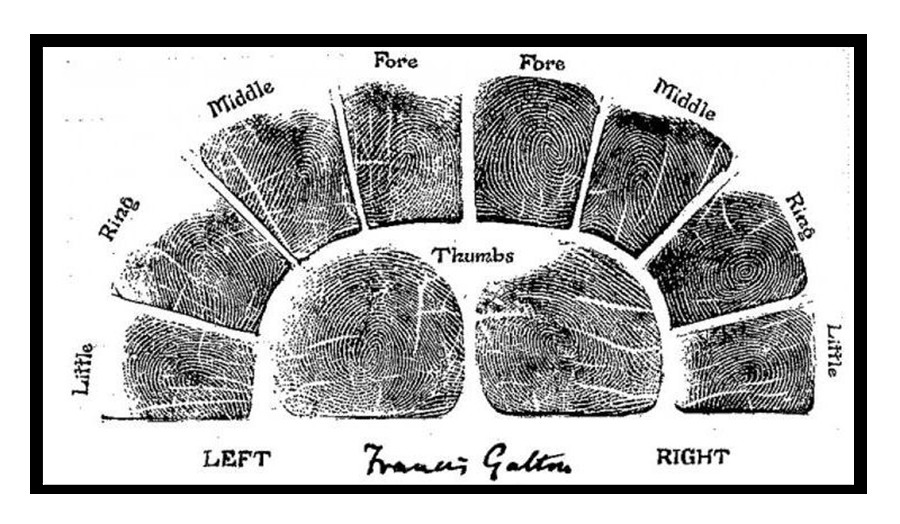

MAMM/MDFSting operations were another area Koshko took into the future. His main contribution was in creating the rule that the details of an operation were to be kept secret, even from the participating cops. Another was setting up a criminal database using dactyloscopic and anthropometric data. The system was first proposed by French lawyer, Alphonse Bertillon. It subsequently spread to Russia and the first anthropometric bureau opened in 1890 in St. Petersburg. It worked in cooperation with the photography department. But law enforcement had hardly ever made use of the data. The arrival of Koshko changed everything. Anthropometry and dactyloscopy gained prominence as useful tools in catching criminals thanks to him. The system’s effects were especially visible in Moscow, where Koshko implemented lessons learned in St. Petersburg.

The latter Paris years

The detective’s professional life was brought to a screeching halt in 1917, with the political changes reducing years of work to nothing. The Provisional Government abolished the police, with many prisons closed, and their former inhabitants roaming the city.

When later the Bolsheviks came to power, Koshko was in serious danger. He did not share the group’s political beliefs. At first, he tried to wait out the storm in his home in Novgorod Province, but that, too, soon put the family in danger. They then relocated to Kiev and Odessa from there. Finally, the family moved to Sevastopol.

With wife, Zinaida Aleksandrovna and younger son, Nikolay

Archive photoWhen Crimea fell to the new government, Koshko immigrated to Istanbul, where he finally planted his roots. He set up a small private investigator’s business, which mainly solved cases of missing items or female marital infidelity. The work, of course, was a shadow of the kind of activity Koshko was used to, but it was guaranteed a stable tomorrow. However, that soon changed, as rumor spread that the Turkish and the Bolsheviks had reached an agreement whereby all Russians would be deported home. The Koshko family fled once again. This time to Paris.

Arkadiy Koshko never changed his citizenship. For this reason, he could not continue his investigative career in France, nor in Britain, for that matter. And it’s not like Scotland Yard didn’t ask - all he had to do was change his nationality and become a British citizen.

Koshko continued to live in Paris and worked as a store salesman, while working on his memoirs. He wrote: “I don’t live in the present, or the future - it’s all in the past and only memories of it kindle some sort of moral satisfaction.”

Koshko passed away in late 1928. The Russian Empire’s most prolific detective is buried in Paris.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox