Why did Norway secretly exhume the bodies of THOUSANDS of Soviet soldiers?

In the summer of 1951, Norway carried out one of the most classified operations in its history, known as ‘Operation Asphalt’. During its course, the remains of thousands of Soviet soldiers, buried in different parts of the country, were secretly exhumed and taken away to be buried in a single cemetery on an island in the Norwegian Sea. What could possibly have led the Scandinavian nation to decide on such an inhumane measure?

The roots of the conflict

In the course of World War II, about 100,000 Soviet POWs were held in Norway. Nazi Germans used them for hard labor, which involved working the mines and in construction, as well as building fortifications in the event of an Allied attack.

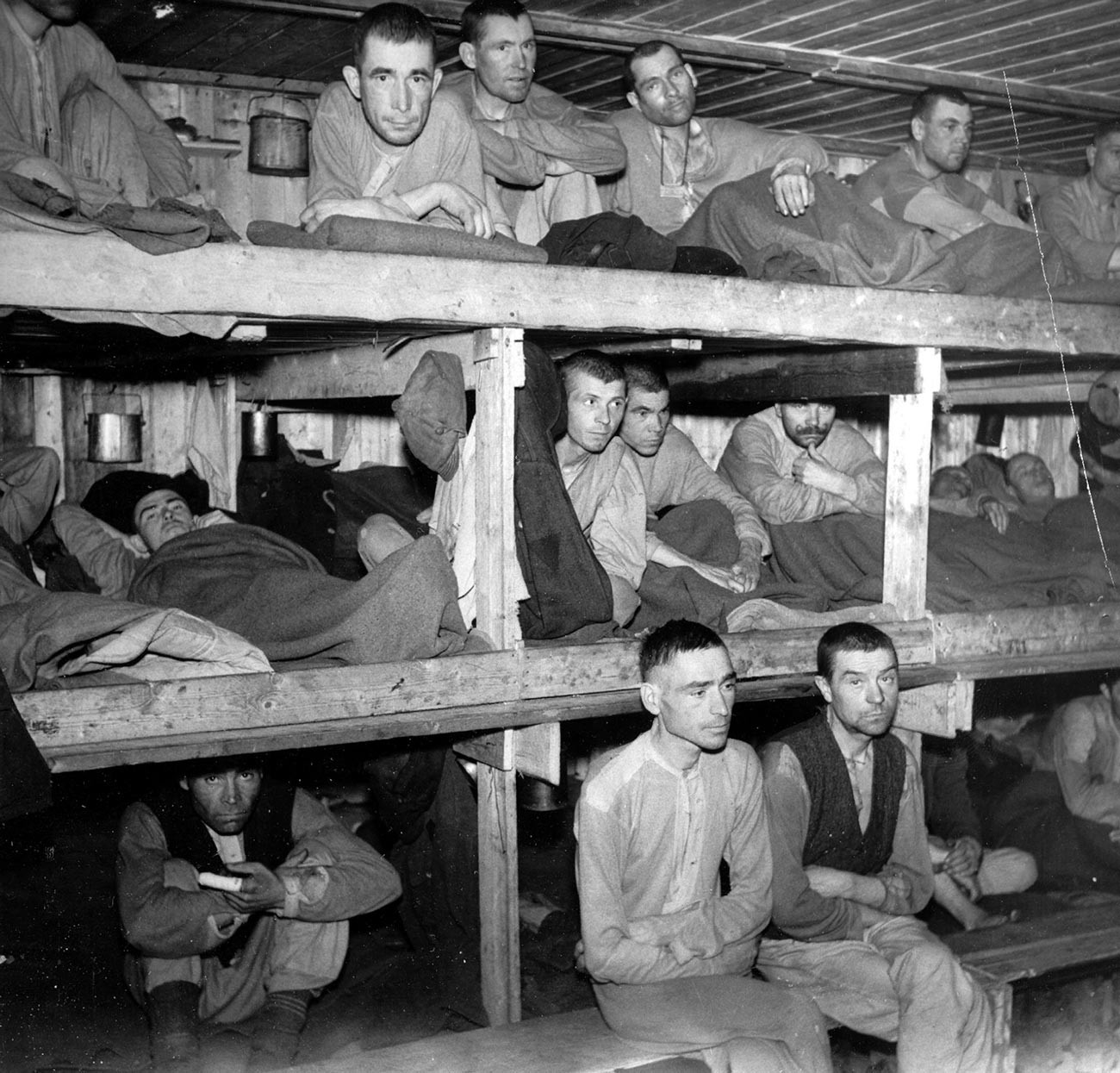

Soviet POWs at Bjørnelva camp.

Leiv Kreyberg/National Archives of NorwayMore than 13,000 of these prisoners died and were buried in several hundred different cemeteries, mostly in the north of the country. After the war, Norway and USSR jointly watched over the remains, making sure that they were tended to appropriately.

However, as years went by, the Cold War gathered steam and, with it, a growing animosity toward their eastern neighbor (Norway had just joined NATO in 1949). Because the business of tending to the graves needed to involve regular visits by Soviet delegates, Oslo was growing understandably wary of the possibility of the Soviets simply injecting their spies into the Norwegian midst this way.

Soviet prisoners of war behind barbed wire at Falstad camp.

The Falstad CentreSurveilling Soviet citizens scattered across their country’s territory, as they visited numerous grave sites, would have been impossible. In order to have complete control over the process and prevent the creation of a widespread and solid network of Soviet spies, the Norwegian Ministry of Defense opted to destroy the numerous cemeteries, exhume the bodies and ship them off to a specially built war cemetery on the island of Tjøtta.

Operation Asphalt

When the Korean war started in summer 1951, the East-West relationship had become even more strained. Norway’s defense ministry then set about quickly carrying out ‘Operation Asphalt’, which owed its name to the literal means by which the transportation was accomplished - using heavy-duty asphalt bags.

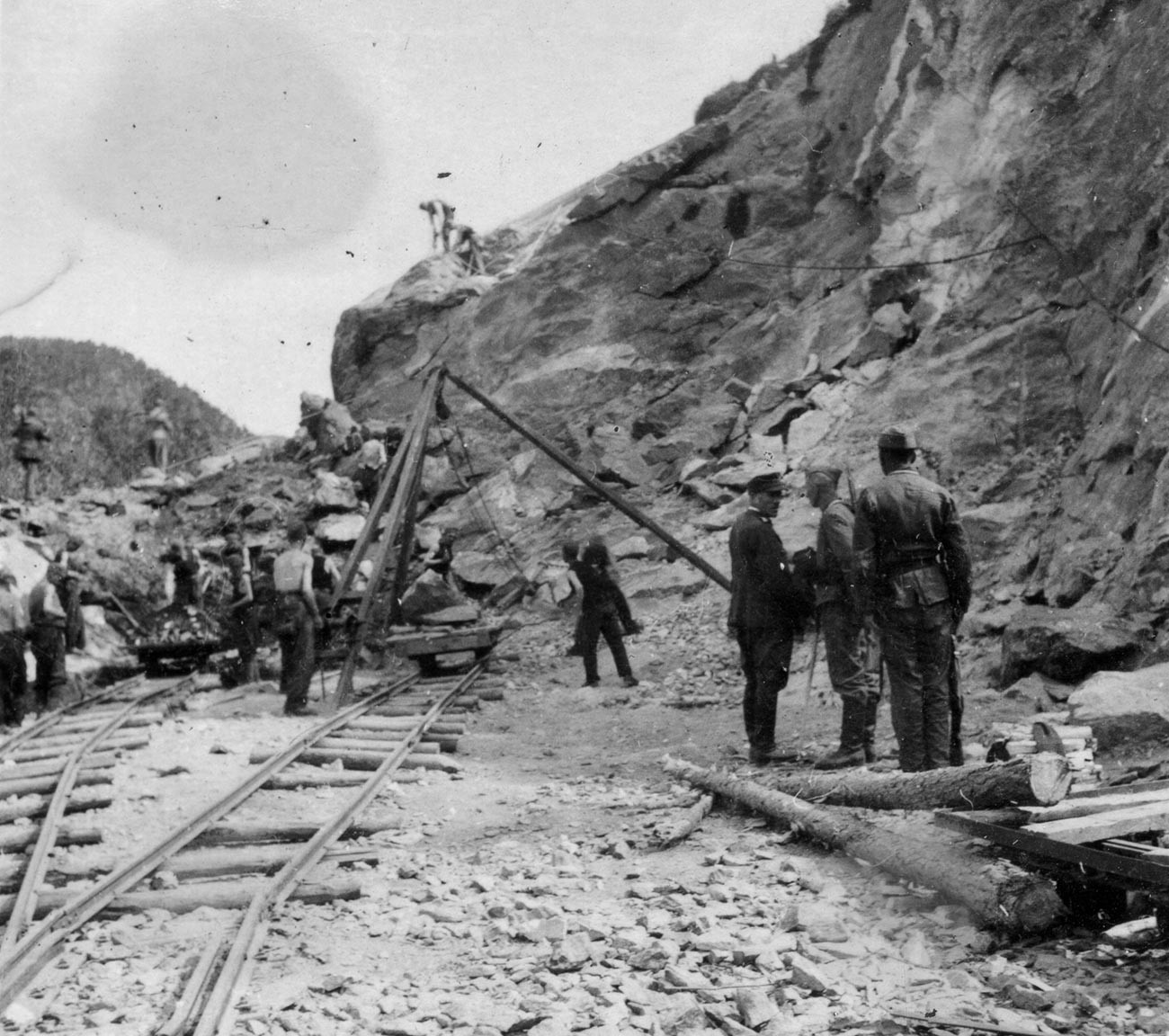

Soviet POWs construct "Blood Road".

Archive photoThe operation was performed in secret, with work carried out mostly at night. Many of the monuments across multiple cemeteries had to be blown up simply to get to the remains.

Tor Steffensen was among the workers who took part in the digs in Finnmark. “We were gathering body parts into different bags. Legs, bones and ribs were everywhere, often belonging to different people. A number of parts belonging to the same person could easily end up in different bags." According to Steffensen, a great number of workers had been having psychotic breaks afterwards.

Ship holds in cargo ships carried the remains from different parts of Norway to Tjøtta. They would have to constantly be disinfected with chlorine, caustic soda and phenol. Jan Brovold, who worked on offloading, remembers vividly the sight of ship hold being filled to the hatchway with bags. “Everything was bursting with them, up to the hatch. They lay like bricks, from the ship’s nose to the tail.”

Opposition

Despite the fact that the operation was classified, word of it somehow broke through to the press. Soon thereafter, Norwegian society became fully aware of ‘Asphalt’ and a massive scandal erupted.

Memorial stone of the around 5,000 Soviet prisoners, who built Rana's part of Nordlandsbanen (Nordland railway) during WWII.

Sandivas (CC BY-SA 3.0)The country’s leftist movements spearheaded the public outcry - chief among them the Communist Party. Nevertheless, even their political rivals were up in arms over the defense ministry’s operation. The leader of the Conservative Party, Carl Joachim Hambro, branded it a “terribly gruesome deed”.

Norwegian civilians, however, were the loudest voice of protest - particularly those residing in the areas where the exhumations were taking place. With the war still fresh in their minds, many had still remembered the prisoners - people they had tried to help with food in any way possible. It was in large part due to that assistance that the majority of the Red Army prisoners had survived.

Soviet cemetery in northern Norway.

Archive photoThe protesters accused the government of the desecration of graves and barbarism. They piqueted the Parliament in Oslo, while in Mo I Rana, the exhumation was successfully prevented altogether.

The USSR was, of course, also strongly critical of the operation, having only learned of it in the final stages, after word of the protests had reached the Soviet government. The official reason they were given was that it would simply have been easier for them to have their dead all neatly buried and accessible in a single place.

The protest note sent by Soviet diplomats included accusations of “trampling the memory of Soviet soldiers”, as well as it being a “hostile act toward the Soviet Union”. The dismantling and, in some cases, destruction of memorials elicited particularly strong criticism.

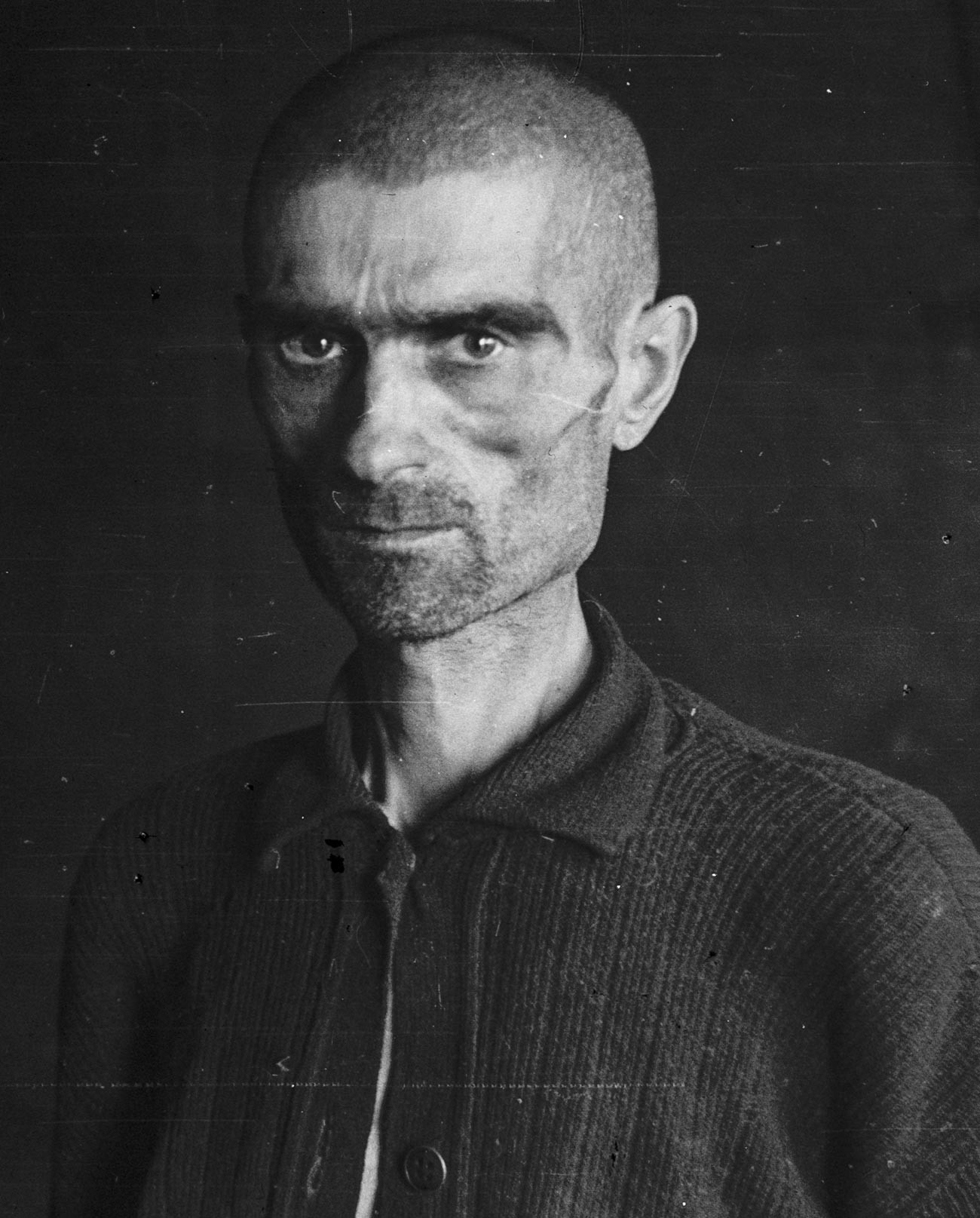

Soviet POW at Bjørnelva camp.

Archive photoOperation Asphalt was completely wrapped up by the winter of 1951. The operation spanned some 200 burial sites across Norway. According to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the island cemetery contained the remains of 8,804 Soviet prisoners - with only 978 of those having been identified.

Despite the fact that the Soviet Union and Norway had continued their cooperation with regard to the re-burying of the Red Army’s soldiers, relationship between the two countries was soured for many years after.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox