‘The Japanese Solzhenitsyn’: How a Communist from Japan survived the Gulag

The political persecutions in the USSR in the 1930s-1950s under Joseph Stalin's leadership had a huge impact on Soviet society: According to the most conservative estimates, over 786,000 people were killed in the state terror campaign and about 3.8 million were sentenced to prison or forced labor camps.

Interestingly, Japanese communist Kinmasa Katsuno was one of the first to publish a book documenting life in the Gulag (the generic term used to describe the punitive system of labor camps and prisons in the Stalin era; the acronym "Gulag" is derived from the Russian name of the Main Directorate of Forced Labor Camps). His books, Permafrost - Notes from a Stalinist Concentration Camp, and Diary of Escape from Communist Russia, were published in Japan in the 1930s when Katsuno, having survived years of slave labor in inhuman conditions, returned to his homeland. But how did he end up in the USSR in the first place?

'Madman' from Nagano Prefecture

Born in Nagano Prefecture in 1901, Katsuno was a champion of the interests of the common people from an early age. When he was just 15, he gave a lecture in a village social club on the unfairness of the state structure. "Two days later I was arrested by police and spent two days in detention. The story caused a stir in our village - there was an article in the local paper which described me as a ‘madman’," he recalled in his autobiography written in a Soviet labor camp in 1934.

Of course, the young man wasn't mad. Rather, he was an enthusiast with a keen sense of justice and fascinated by Marxist ideas. Katsuno wasn’t one to compromise and, as a result, constantly ended up in trouble: For instance, in 1918 he was kicked out of Nihon University after writing an article demanding that education be democratized.

The dedicated and able student entered another university, Waseda. There he found like-minded people with whom he published magazines affiliated to left-wing parties, took part in protests and was arrested twice. As Japan became more militarized, the government started treating left-wing activists increasingly ruthlessly. So in 1924 Katsuno left Japan for France.

Teaming up with foreign comrades

French communist demo in Paris

Getty ImagesIn Paris it was back to square one for the Japanese activist: A hand-to-mouth existence, studying (this time at the Sorbonne), meeting local Communists, and taking part in protests. "Demonstrations often took place in Paris. Once, a young Communist girl grabbed me by the hand, saying: ‘Come on, you Japanese guy, join us!’ I still remember the exultation I felt at that moment. After joining the French Communist Party, I took part in organizing workers' strikes. I had the feeling that soon there would be a world revolution," Katsuno recollected later.

As in Japan, the French authorities were not delighted with Katsuno's activities and in 1928 he was deported. "You can stage a revolution anywhere you like, but not in France," were the words of the local police, as recorded by Katsuno. Via Germany and with the help of the Comintern (Communist International) - the world Communist movement - he travelled to the USSR. It would seem that the left-wing activist couldn't have any problems there.

The Moscow trap

It all started well: In Moscow, Katsuno enjoyed the patronage of Sen Katayama, a veteran of the political struggle in Japan and an important Comintern figure. Katsuno worked as Katayama's secretary, taught Japanese at the Institute of Oriental Studies, and wrote for Soviet newspapers and also underground publications in Japan, which the Comintern helped to publish. Katsuno genuinely planned to stay in the "land of workers and peasants". He learned the language, became a Soviet citizen and was even given a Russian pseudonym - Alexander Ivanovich. Soon, he would be using this name to countersign his own arrest documents.

Leade of the Japanese Communist Party, Sen Katayama (1859-1933)

SputnikAs explained by the staff of Moscow's Gulag History Museum, Katsuno found himself in trouble because of an internal power struggle inside the Japanese branch of the Comintern: Political opponents of his mentor Katayama accused his faction of treason, as a result of which many Japanese Communists, including Katsuno, found themselves behind bars.

"In late October 1930, I was waiting at a tram stop. The falling snow caressed my face with its cold touches. At that moment someone forcefully grabbed me by the arm. I saw that I was hemmed in by two sturdy men in peaked caps. I was brought to the main OGPU building [Russian abbreviation for the Joint State Political Directorate - forerunner of the NKVD] at Lubyanka," is how Katsuno described the day of his arrest. He was accused of espionage on behalf of a foreign state.

On the great Stalinist construction site

The OGPU had no evidence of Katsuno's guilt: As can be seen from the interrogation records, he was asked why he maintained contacts with scientists and members of the military, and he was baselessly accused of passing information to Japan. "I categorically confirm the utter absurdity of the accusations of espionage levelled against me," wrote the Comintern official. In the 18 months he spent in prison, he twice declared a hunger strike and demanded that he either be shot or released.

Instead, he was sentenced to five years and initially sent to a Siberian prison camp near Mariinsk in the Kemerovo Region (3,645 km east of Moscow) and then to the construction site of the White Sea-Baltic Canal (1,100 km north of Moscow). It was a vast and inhuman project of the Stalin era - more than 100,000 prisoners were required to build the 227-km canal between the White Sea and Lake Onega in 20 months without the use of equipment and relying just on shovels and wheelbarrows.

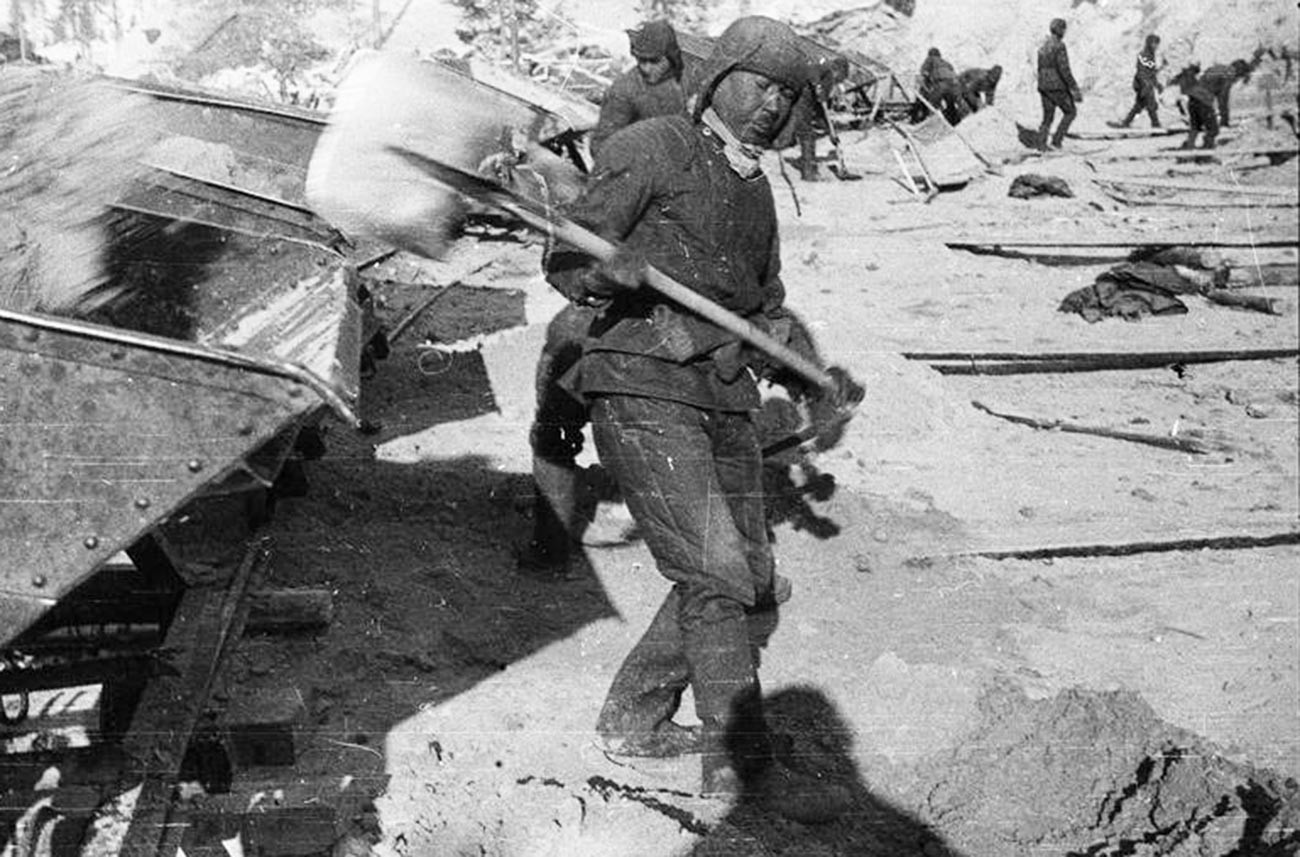

Prisoners on the construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Alexander Rodchenko/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ru"It is fearfully quiet. Beyond the horizon of the White Night lingers a faint daylight without light. Multitudes of people have been sent here. But they have all been brought here as forced labor," is how Katsuno recalled the camp. Every day from five o'clock in the morning to midnight they had to break stones and move soil. There were no days off and no rest, and anyone who failed to meet their daily target had their rations cut.

The construction of the White Sea-Baltic Canal

Alexander Rodchenko/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruKatsuno survived by a miracle - after sustaining a serious injury on the construction site, he was transferred to a medical station, where he remained assisting doctors until the end of his sentence. It was a rare good outcome for a prisoner of the White Sea-Baltic Camp - according to different estimates, between 12,000 and 50,000 people perished during the canal’s construction.

Farewell to the USSR

In June 1934, Katsuno was granted early release. After what he had seen and experienced in the camps, the former activist had clearly become disillusioned with Communism. Back in Moscow, without waiting to be arrested a second time, he went to the Japanese embassy and was repatriated.

Kinmasa Katsuno

Alexander Solzhenitsyn House of Russia AbroadBy summer 1934, articles were already appearing in the Japanese newspapers about "lost illusions" over "Red Russia" in which Katsuno related what he had lived through in the Soviet camps: The Japanese government used him for anti-Communist propaganda. At the same time, Katsuno, who was to be dubbed the "Japanese Solzhenitsyn" in reference to the Russian writer whose prose was devoted to a depiction of the Gulag, preferred to distance himself from politics. He published his memoirs, devoted himself to the family business in the timber industry, as well as charity work, and lived a long life. He died in 1983, thirteen years before the Russian government fully rehabilitated the Japanese citizen of the USSR, "Alexander Ivanovich".

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox