How the USSR helped the Communists seize power in China

In 1949, the Communists won a decisive victory in the Chinese Civil War, defeating their implacable enemies, the Kuomintang national conservative party under Chiang Kai-shek. The Soviet Union provided no small help to them in this.

Interestingly, not long before, it was the Kuomintang that had been the USSR’s main ally in China, while the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) had only been of secondary importance for Moscow.

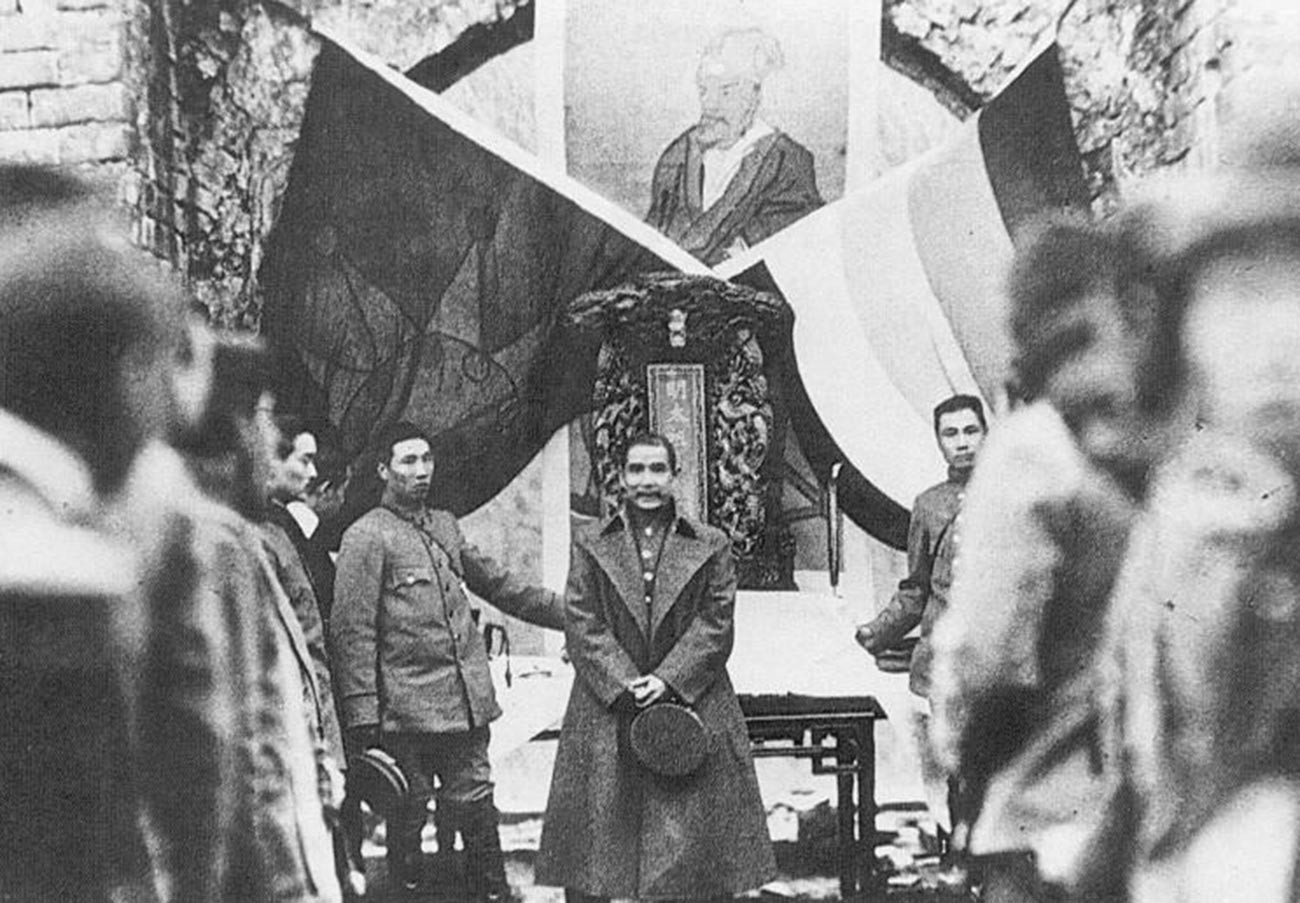

United front

The first leader of the Kuomintang Sun Yat-sen in 1912.

Public DomainSoon after the collapse of the Qing Empire in 1912, China became a fragmented and weakened state with no strong centralized power. The country was essentially divided among military and political cliques that endlessly squabbled with one another. And foreign powers didn’t hesitate to take advantage of this by interfering in China’s internal affairs.

Few Chinese were happy with the situation and, in the 1920s, two forces entered the political arena intent on leading the country out of the medieval feudalism in which it found itself.

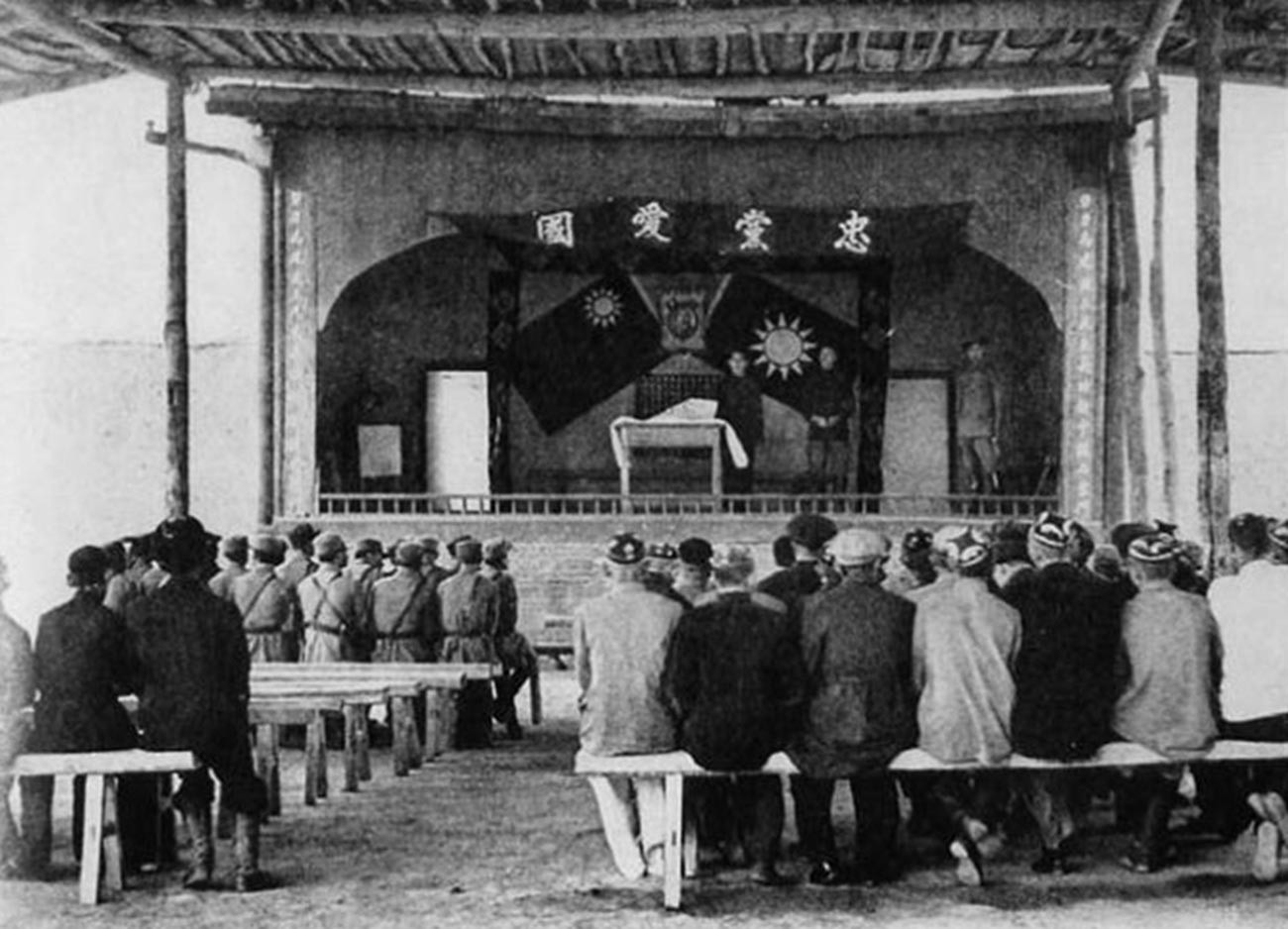

Kuomintang party meeting in Xinjiang.

Public DomainThe future sworn enemies - the Kuomintang and the CCP - acted together this time. In 1922, they jointly formed the First United Front, in the creation of which the Bolsheviks played a key role.

Cooperation between the USSR and the Kuomintang

Moscow not only closely followed the events in China, but also took an active part in them. Finding itself isolated by the world community, Soviet Russia (and from 1922, the USSR) sought allies abroad. Its offer of cooperation having been turned down by the Beiyang clique (which was recognized as the official government of China, although it had little control of the country), the Soviet government decided to back the Kuomintang, founded and led by Sun Yat-sen.

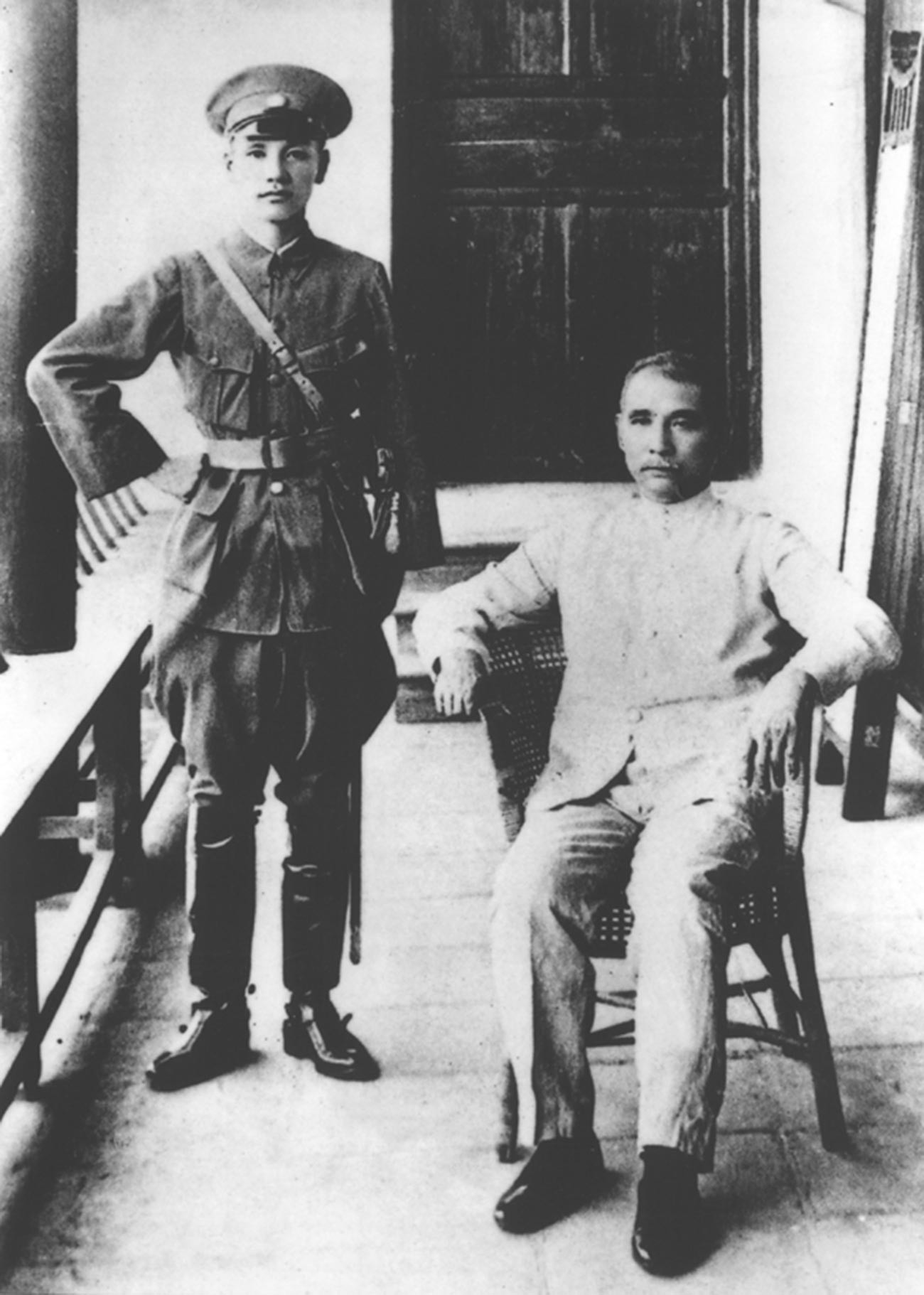

Chiang Kai-shek and Sun Yat-sen in 1924.

Public DomainThe Kuomintang was chosen by Moscow because it was then more numerous and influential than the CCP. It was the Kuomintang that was supposed to become the Bolsheviks’ support base in China and their loyal ally in the struggle against the Western powers.

The USSR helped reorganize the Kuomintang’s National Revolutionary Army and supplied it with weapons and ammunition. The Communists, who, at Moscow’s request, sided with Sun Yat-sen’s party, received much more modest assistance.

Generals of the Kuomintang’s National Revolutionary Army.

Public DomainMoscow tried to nip in the bud any disagreements that emerged between members of the two parties. The CCP leadership received unequivocal instructions from the Kremlin to make concessions to their comrades for the sake of preserving unity.

The break

In 1926-1928, with the participation of Soviet military specialists, Chiang Kai-shek, the new leader of the Kuomintang, organized the so-called Northern Expedition against a number of military and political cliques, which culminated in the unification of China under his authority.

Chiang Kai-shek in 1933.

Public DomainOn April 12, 1927, even before the completion of the expedition, the Kuomintang, being unwilling to share power, carried out a surprise strike against its allies. Mass arrests and executions of CCP members took place in a number of cities.

Intent on freeing himself from Moscow’s tutelage, Chiang Kai-shek embarked on a sustained anti-Soviet policy, forcing the Communist Party to go to ground. In consequence, on December 14, 1927, diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and China were broken off.

Reconciliation

Chinese Hui soldiers led by a Communist Ma Benzhai.

Public DomainWith the invasion of the country by Japanese forces in 1937, the Civil War in China was halted for a time. The establishment of a Second United Front between the Communists and the Kuomintang was accompanied by a restoration of relations between Nanking (the then capital of China) and Moscow, which regarded Japan as a threat to its own security. Soviet military advisers and pilots started arriving in the country, as did arms and munitions.

In 1941, the New China newspaper wrote: “Over the four years of our sacred war, the most important and reliable foreign assistance has come from the Soviet Union.” As before, its main beneficiary was the Kuomintang, which was in charge of the country, while the CCP had to settle for little. Moscow insistently advised it to follow government policy, in order not to destroy the united front.

National Revolutionary Army troops.

Public Domain“The Communists would seem to be closer to us than Chiang Kai-shek,” recalled Vasily Chuikov, one of the Soviet military advisers in China. “It would seem that the bulk of our assistance ought to be given to them… But this assistance would look like the export of revolution to a country with which we are linked by diplomatic relations. The CCP and the working class are still too weak to take the lead in the struggle against the aggressor. It will take time - it is difficult to say how much - to win the masses over to the cause. Apart from anything else, the imperialist powers will hardly allow Chiang Kai-shek to be replaced by the Communist Party.”

Even after outright attacks by Kuomintang troops against the Communists (such as the encirclement and destruction of the HQ of the CCP’s New Fourth Army in January 1941) Moscow appealed to the Communists for restraint, guided as it was by the principle, “everything for the resistance against Japan”. At the same time, the USSR also curbed Chiang Kai-shek in his military campaigns against provinces controlled by the Communist Party.

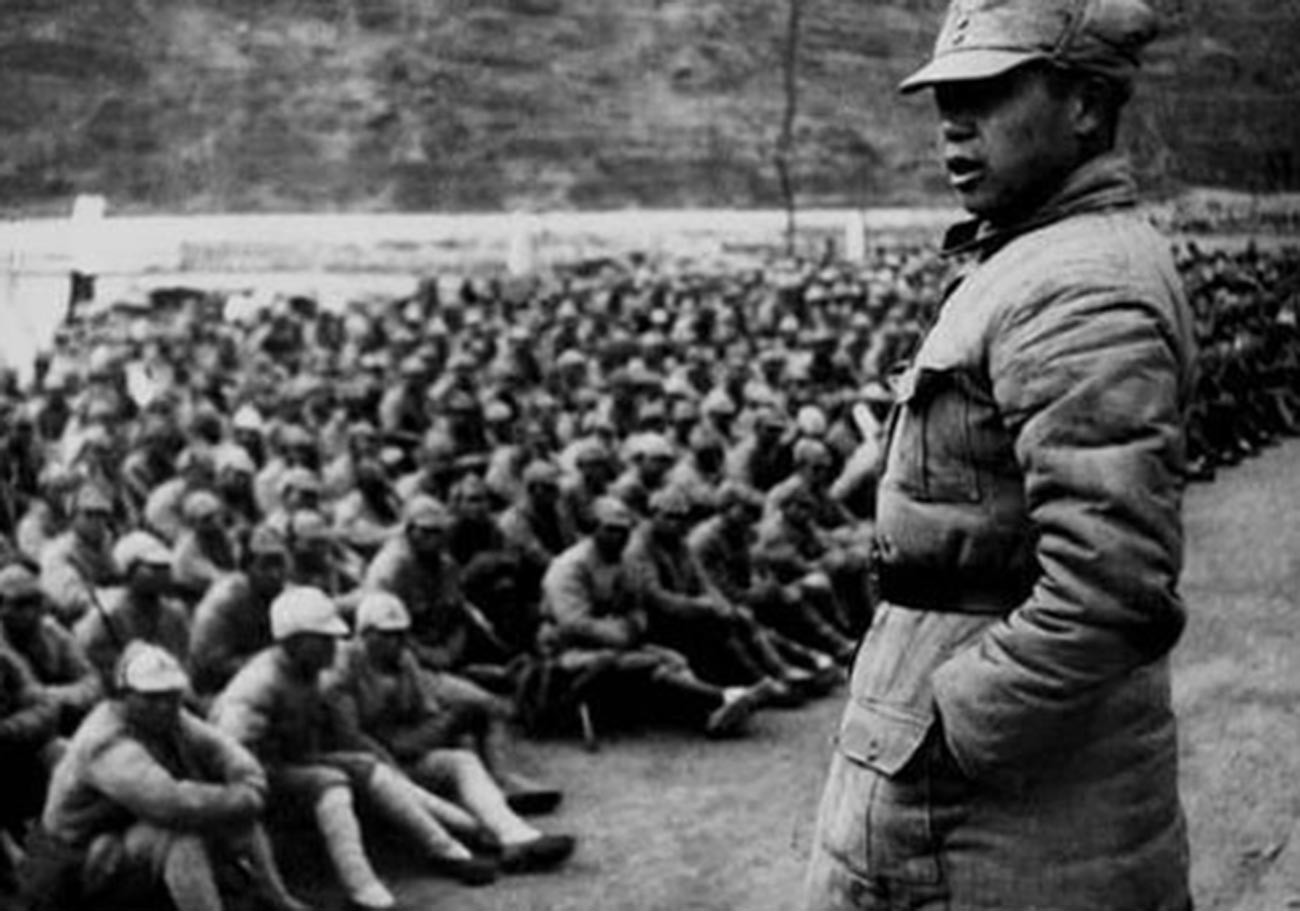

Communist leader Chen Xilian addressing the Chinese People’s Liberation Army soldiers in 1940.

Public DomainWith Nazi Germany’s attack in June 1941, the Soviet Union lost interest in China. Assistance to the Kuomintang and the CCP almost completely ceased. It was only with the end of the war in Europe that Moscow once again turned its attention to the problems of the Far East.

Long-awaited assistance

Alongside mounting rapprochement between the Kuomintang and the U.S., Soviet support for the Chinese Communists also increased. Officially, the Soviet Union and the government of Chiang Kai-shek continued to maintain respectful relations. On August 14, 1945, they even signed a Treaty of Friendship and Alliance under which they were supposed to fight against Japan together.

Soviet infantry crosses the border of Manchuria on August 9, 1945.

Public DomainMoscow rendered the CCP crucial assistance in Manchuria. Red Army units were temporarily stationed in this northeastern part of China after its liberation from Japanese troops. The Soviet administration assisted the clandestine infiltration of Chinese Communists into the region and the establishment of their revolutionary base there.

Specialists from the USSR actively worked to restore the infrastructure of Manchuria and deliveries of vital goods and raw materials began, while Japanese trophy weapons were handed to the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (including 861 airplanes, 600 tanks, artillery, mortars, 1,200 machine guns, rifles and ammunition). In addition, the Soviet Union embarked on the training of the military cadres of the Communist armed forces, while Moscow granted Mao Zedong a preferential loan for warfare.

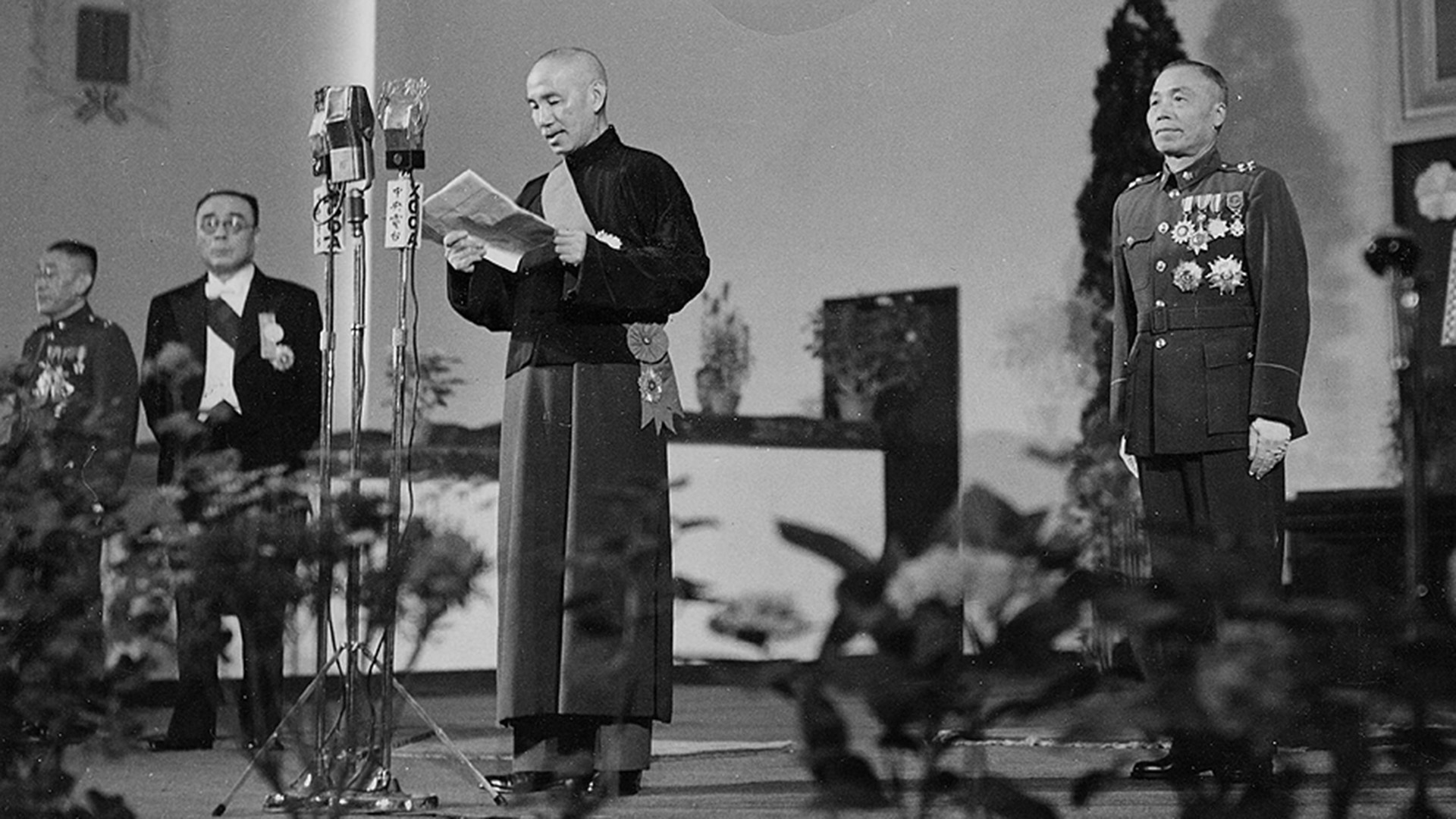

Chiang Kai-shek in 1948.

Public DomainWhen, after the Red Army’s withdrawal, government troops entered Manchuria in April 1946, they were surprised to discover not fragmented CCP partisan detachments, but a modern and disciplined army. Northeast China became the main battleground in the Civil War, which finally ended with the defeat of the Kuomintang and its evacuation to the island of Taiwan.

The Soviet Union had wavered for a long time before openly taking the side of the Chinese Communists. When it did happen, the CCP’s chances of winning the struggle for power in China were boosted enormously. The upshot was that on October 1, 1949, the People’s Republic of China was proclaimed and the first country in the world to recognize it was the USSR.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox