How the U.S. Embassy in Moscow burned in 1977

Malcolm Toon, Jimmy Carter’s choice for the key post of the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union, was having fun at a black tie dinner at the Romanian Ambassador’s residence in Moscow, when an ominous call suddenly interrupted his pleasant evening.

On the other side of the line was young political officer James Schumaker, who had arrived in Moscow only recently. “We’ve got a fire here in...” he began telling the ambassador.

Dinner interrupted

It was August 26, 1977, and James Schumaker has only been in Moscow for a few weeks. On this unusually chilly, but clear summer evening, Schumaker was relaxing at his apartment in Spaso House, the residence of U.S. ambassadors to Russia.

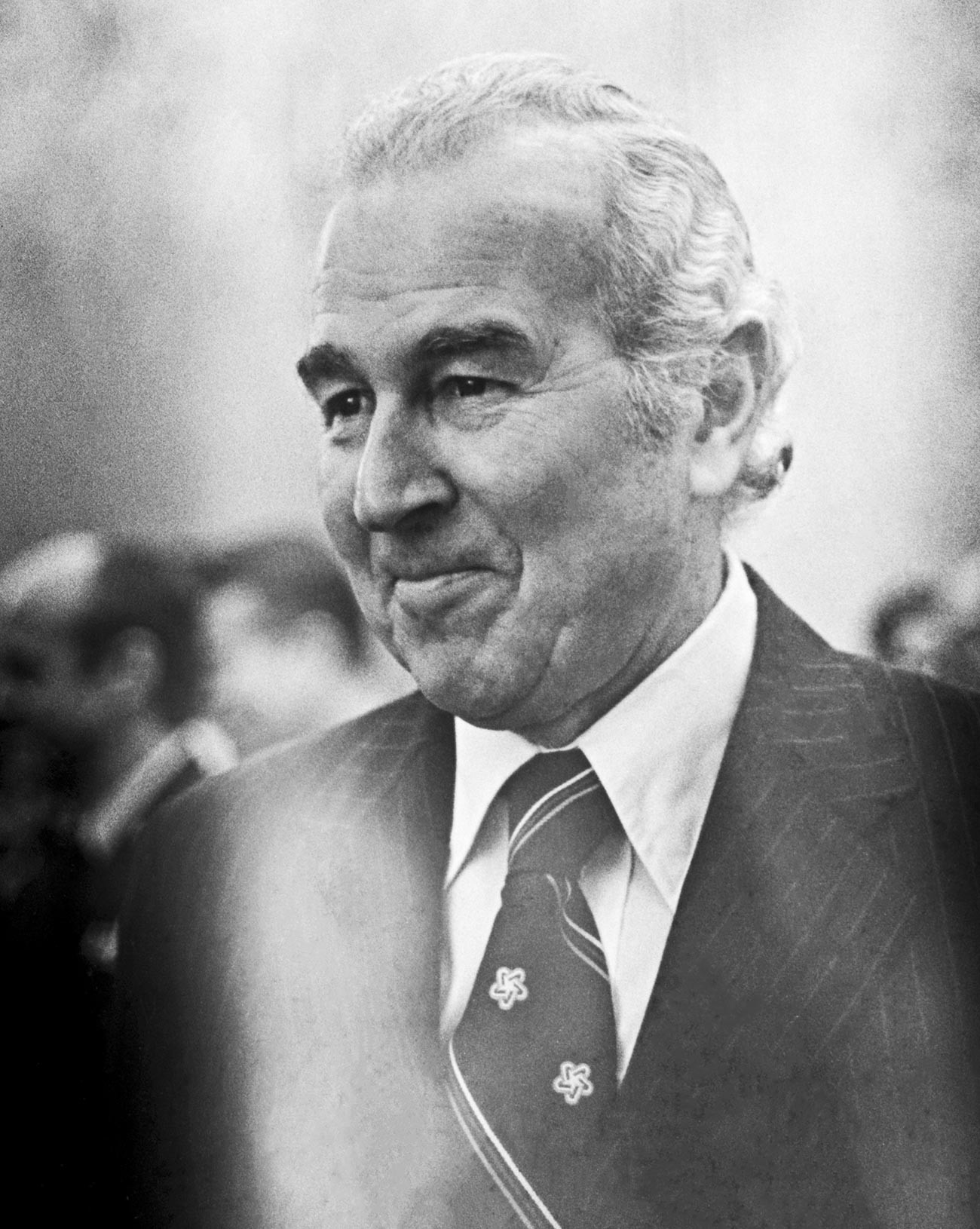

Malcolm Toon, Jimmy Carter’s choice for the key post of the U.S. Ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Viktor Budan/TASSThe phone rang and he came to answer. It was Deputy Chief of Mission Jack Matlock speaking and he sounded agitated. He urgently needed to talk to the Ambassador and instructed Schumaker to locate the latter: “Please hurry, Jim,” Matlock urged.

With the help of Svetlana Alekhina — “our beautiful blonde telephone operator” — he located Toon, who was attending the black tie dinner at the Romanian Ambassador’s residence.

“What’s going on, Jim?” said Toon.

“I don’t know, Mr. Ambassador, but the DCM needs to speak to you right away.”

Another phone buzzed at Spaso House. It was Matlock, yet again.

“Mr. Matlock, I’ve got the Ambassador on the other line. What should I tell him?” asked Schumaker.

“Matlock, the agitation rising in his voice, replied, ‘Jim, tell him we’ve got a fire here in…’ and at that moment the line suddenly went dead,” recalled Schumaker of the ominous conversation later.

‘I lost everything’

When Ambassador Toon and his subordinate James Schumaker arrived at the U.S. Embassy located a few blocks away from Spaso House, they saw the building was engulfed in flames.

“The sight that greeted me was hard to believe. Most of the eighth floor of the Embassy was on fire,” Schumaker said, describing the scene.

The fire was quickly getting out of control and rapidly spreading throughout the building. Ambassador Toon was directing the evacuation effort still dressed — awkwardly for the circumstances — in a formal dinner suit.

Many of the embassy employees were assisting evacuation, some were in a state of shock. Schumaker recalled a scene of Economic Counselor Ken Skoug wandering “up and down in front of the Embassy, mumbling to no one in particular, ‘I’ve lost everything,’ as flames billowed out of his eighth floor office window.”

‘Let it burn’

Soon, the Soviet firefighters arrived at the scene. More and more fire trucks pulled nearby and firefighters set ladders against the burning building.

The Soviet fire brigade commander approached Toon and asked for permission to move to the attic. “Let it burn,” replied the Ambassador.

Anatoli Sergeev-Vasilyev/SputnikSince the U.S. Embassy was considered the territory of the U.S., Soviet firefighters had to receive permission of the Ambassador to enter the building. The Soviet fire brigade commander approached Toon and asked for permission to move to the attic.

“Let it burn,” replied the Ambassador.

“This was because Toon suspected that some of the ‘professional firefighters’ might actually be working for the KGB and because the Embassy had a lot of sensitive equipment under the eaves,” Schumaker explained in a later account.

Eventually, the Soviet firefighters — some of whom the American diplomats suspected to be working for the KGB — were granted access to the Embassy’s upper floors on condition they would be escorted by the Embassy’s military officers.

When the firefighters and the officers worked their way up the building, they discovered some of the Embassy employees hadn’t left the building, despite being ordered to evacuate.

“CIA Station Chief Gus Hathaway [was] guarding his area dressed in a London Fog raincoat and armed with a .38 caliber revolver. On hearing the Ambassador’s order, Gus gave Marc ‘a rather undiplomatic response.’ […] Ambassador Toon was not happy, but there was nothing he could do and Gus stayed behind. Gus, like Toon, was a World War II veteran and knew his duty,” wrote Schumaker.

More and more fire trucks pulled nearby and firefighters set ladders against the burning building. U.S. Embassy in Moscow, August 1977.

Valentin Mastyukov/TASSFortunately, nobody died in the fire although it considerably damaged the building. “The eighth floor had been burned out and every floor from seven on up had suffered smoke and water damage. The Chancery was a wreck, for all intents and purposes,” Schumaker described the scene that he saw the morning after the fire.

Despite their building being damaged, the American diplomats were certain KGB agents had infiltrated later arrivals of the Soviet fire crews. They claimed the disguised agents went through classified files, forced some of the safes open and messed with the Embassy’s equipment.

Soviet firefighters vehemently denied the allegations. General Viktor Sokolov, who served as the Deputy Head of the Fire Department at the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs at the time, said he did not have chekists — agents of the secret police — at his disposal.

The Americans did not believe it, however. When a KGB shed near the Embassy caught fire a few months later, the Marines had drinks and watched the fire to a bit of the song ‘Disco Inferno’ by The Trammps.

Burn, Baby Burn

Burn that mother down

Disco inferno

Burn that mother down

Click here to find out how Soviet Alfa Spec Ops ‘neutralized’ a terrorist inside the U.S. Embassy in Moscow in 1979.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox