The Starostin brothers: How four famous footballers ended up in the Gulag

The Starostin brothers - Nikolai, Aleksandr, Andrey and Pyotr - were footballers famous throughout the USSR. They played in the Soviet national team and for Spartak Moscow and were victorious at various tournaments. Spartak Moscow supporters still hold them in high esteem and Moscow even has a street named after the eldest brother, Nikolai Starostin.

Mural portrait of Nikolai Starostin on the street named after him in eastern Moscow

mos.ruAlas, nationwide admiration didn’t save them from the repressive Stalinist machine and all four were arrested on the basis of ridiculous allegations...

The Starostin brothers’ rise to fame

In 1934, Nikolai Starostin was asked to organize a voluntary sports society, dubbed ‘Spartak’. Following the example of voluntary societies set up by ministries and other government departments, ‘Spartak’ grew out of the athletic clubs of enterprises of the Producers’ Cooperative Society, a non-governmental organization that included a huge number of small production plants in the light and food industries.

The society then set up a football team - Spartak Moscow. It was run using the society’s funds and was supported by ordinary people, rather than representatives of the army or other state organizations. Therefore, Spartak became known as the “people’s team”.

The four brothers became Spartak players and Nikolai was also appointed the manager of the team, dealing with its affairs. Thanks to the talented footballers, the team showed its class from the very beginning, winning several tournaments.

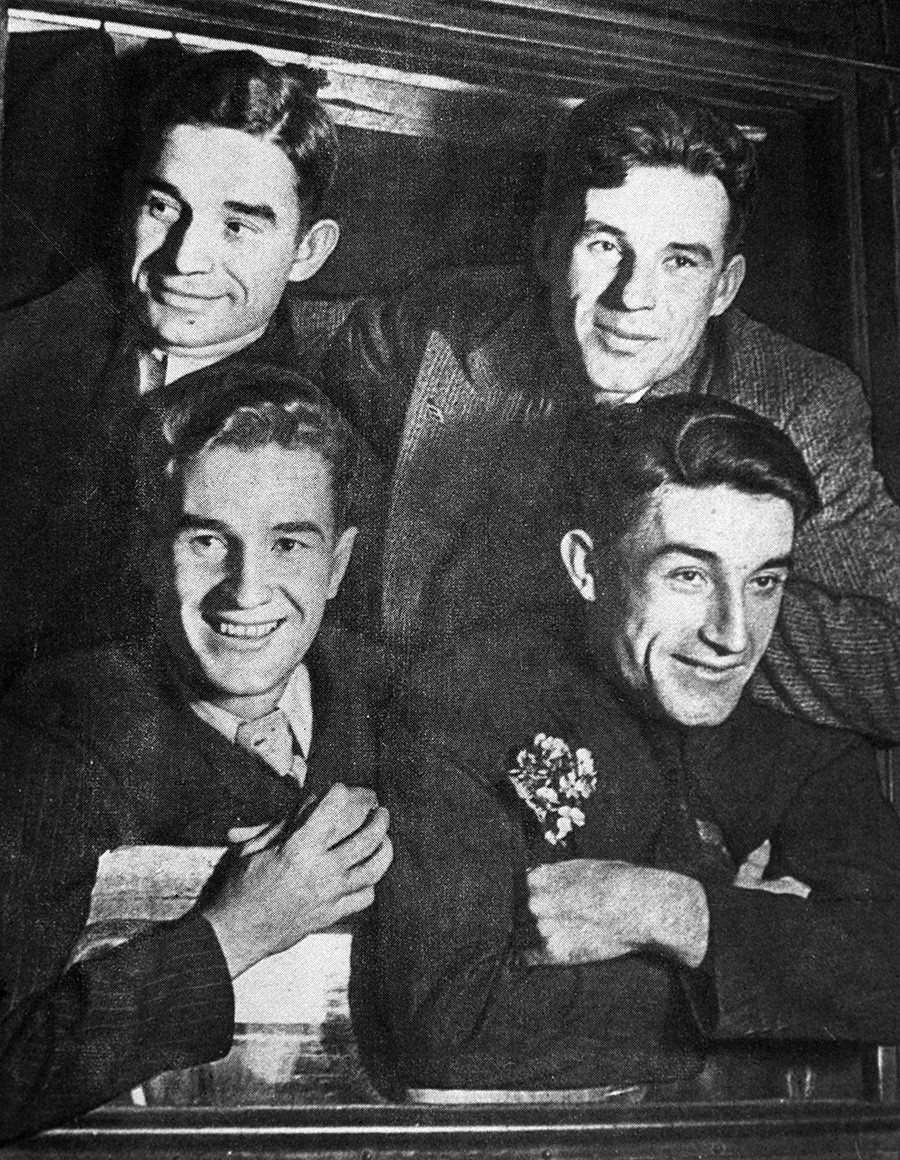

Football team of the Producers’ Cooperative Society in 1934. Andrei Starostin - 4th from left, Nikolai - 5th from left, Alexander 7th from left, Pyotr - 3rd from right)

Ogonyok MagazineAt the time, the USSR was not taking part in ordinary Olympic competitions or championships, regarding them as “bourgeois” and harmful. But Soviet athletes did participate in international competitions of workers’ organizations. In 1937, Spartak triumphantly won the football tournament at the III Workers’ Summer Olympiad in Antwerp, Belgium.

In the same year, the Spartak players were honored in Stalin’s favorite spectacle - the Physical Culture Parade on the Red Square. The footballers drove past Stalin in an enormous football boot with the inscription “Spartak - Spain (Basque Country) - 6 : 2” in celebration of their victory over the Spaniards on the eve of the parade.

How the Starostin brothers fell out of favor

Spartak repeatedly beat football clubs belonging to government departments inside the USSR, too. They included Dynamo, the team of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (NKVD). Rumor had it that the NKVD leadership was annoyed with the “people’s team” beating their “own” team.

In 1937, the NKVD issued a decree targeting “former kulaks [wealthy peasants], criminals and other anti-Soviet elements”, which marked the beginning of Stalin’s Great Terror. Anyone could be branded as an “anti-Soviet element”.

READ MORE: Struggling with the facts: How terrible was Stalin’s Terror?

The champion footballers from Spartak used to travel to bourgeois countries, but the trouble was that the NKVD regarded any contacts between Soviet citizens and foreigners as suspicious. At one point in 1937, several Soviet newspapers accused the Spartak players of wasting “the people’s” money, collected through voluntary contributions by members of their sports society, on such trips.

The players were also accused of receiving salaries out of these funds. And this was forbidden - there was no paid professional sport in the USSR and athletes were amateurs who were not supposed to receive any pay.

Nikolai Starostin in 1938

V.Krasinskaya/Sputnik“We must decisively cleanse the sports societies, and Spartak in particular, of bourgeois backsliders and dirty dealers who dip their hands in the public purse,” said the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper.

Subsequently, a wave of arrests swept through the circle of the Starostin brothers - many people were accused of plotting the assassination of Stalin at a physical culture parade. During interrogation under torture, investigators forced a confession out of one of the athletes to the effect that a counterrevolutionary terrorist group was operating inside Spartak and that it was led by [Nikolai] Starostin himself.

How the Starostin brothers ended up in prison

The brothers were spared arrest during the Great Terror itself. It was believed that Spartak’s founders had protectors in the NKVD. The leadership of the ministry later changed, however, and, in 1942, Nikolai, Pyotr and Andrey Starostin were arrested. The NKVD raided the apartments of all three without warning - on the same night. Six months later, the fourth brother, Aleksandr, was also put in prison when he returned from the front of World War II.

The Starostin brothers, 1936. In the bottom L-R: Pyotr and Andrei, on top L-R: Nikolai and Alexander

SputnikIn their memoirs, the brothers say they were interrogated, beaten and maltreated for a year and a half by investigators who wanted to force a confession out of them to the effect that they had been plotting to assassinate Stalin, but the brothers had nothing to confess.

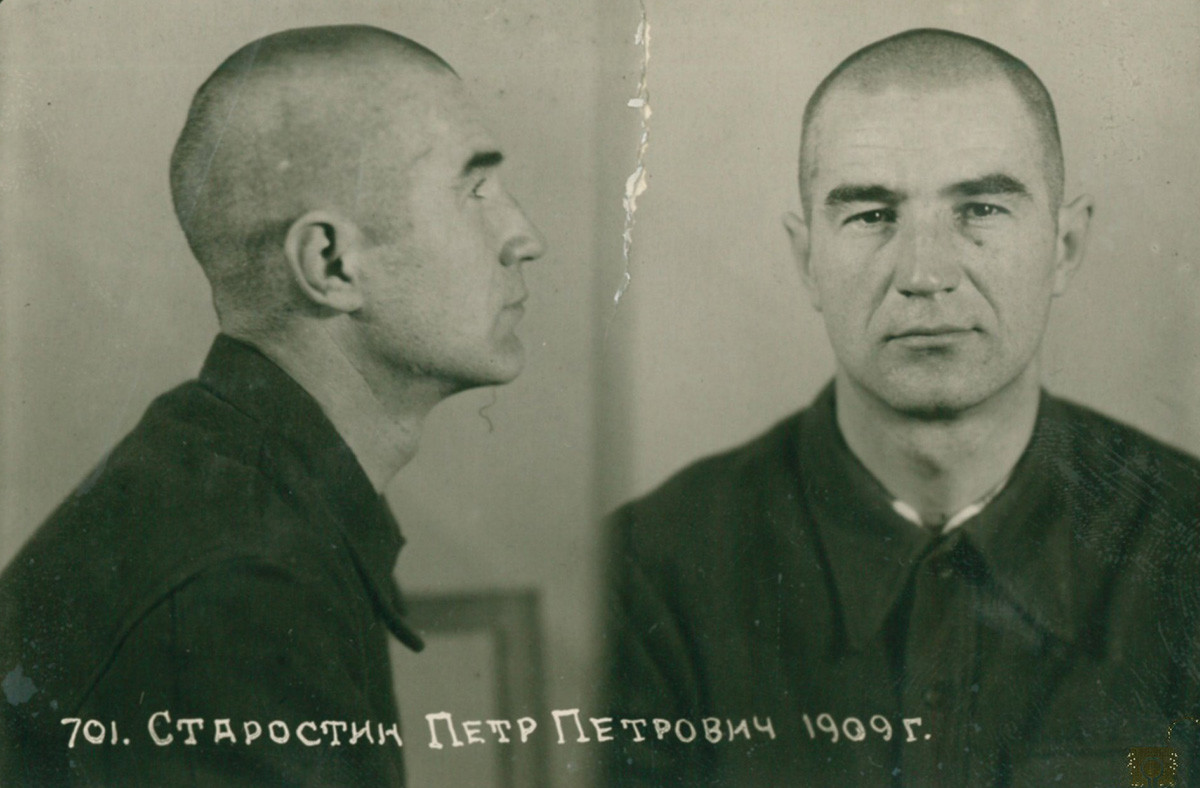

In the end, during an ochnaya stavka [an investigative procedure in which suspects are confronted with others involved in the case], the brothers decided to “confess” to lesser “crimes” to escape further interrogation and torture. Nikolai, Aleksandr and Andrey confessed to alleged squandering of public funds. They were charged with “praising bourgeois sport and attempts to infiltrate bourgeois values into Soviet sport”. Pyotr confessed to criticizing collective farms and low wages and he was convicted of anti-Soviet propaganda. All three were sentenced to 10 years in prison camps.

How the Starostin brothers survived the camps

Although all four brothers were sent to different camps, they were in one sense fortunate. They had at least avoided execution. All the brothers, with the exception of Nikolai, were assigned to hard labor.

Pyotr recalled the winter of 1944 as one of the most difficult periods of his entire time in prison camp. “Stalin’s decree is being applied to its full extent - harsh measures up to and including execution are to be applied for refusing to work. So we go out to our work assignments with a supreme effort of will. Many men have been collapsing along the road. Daily fatality rates have been reaching 40.” He was issued with just 750 grams of bread a day. At the height of the war, prison camp inmates had their rations cut, even though they had to work even harder to meet the needs of the front.

Pyotr Starostin in jail

Archive photo“My football connections were my best safe conduct pass,” wrote Nikolai. He was luckier than his brothers - he did not end up being pressed into hard labor, but was immediately appointed coach of the camp’s football team. Nikolai was later sent to the Far East, where, by an ironic twist of fate, he was made to train the local Dynamo team. Subsequently, he was even allowed to stay off site and arrange for his family to come and live with him.

How Stalin saved Nikolai Starostin

The year 1948 saw an event that Nikolai Starostin would later describe as a “true story with an unbelievable plot”. He was called to the telephone and told that the person at the other end was none other than… Stalin. It turned out that Stalin’s son Vasily, who was well-known for promoting sport, wanted to speak to the famous footballer. He. He told Nikolai, without beating about the bush, that he was trying to get him freed: “They jailed you for nothing, that's obvious.”

With Vasily Stalin’s influence, Starostin was sent to work at a factory and for each day he fulfilled the norm, a two-day reduction was applied to his sentence. Finally, after two years, Nikolai was released early from prison camp.

Joseph Stalin's son Vasily Stalin (R)

Archive photoVasily Stalin wanted Starostin to coach his Air Force football team. The trainer was brought to Moscow, where he was even issued with a residence permit, enabling him to register in his old apartment. But even Stalin’s all-powerful son could not openly contravene the law - former camp inmates were not allowed to live within a 100-km radius of Moscow. So, Starostin’s residence permit was rescinded. Then, Vasily made another attempt to allow the talented trainer to stay in Moscow - he gave him accommodation in his own official residence. Later, in his memoirs, Starostin recalled these events and made ironic references to his “tragicomic” plight as “a man on familiar terms with the offspring of the tyrant” and to the fact that they were “doomed to be inseparable”. “We travelled to headquarters together, to training sessions and to the dacha. We even slept in the same enormously wide bed. Moreover, Vasily Iosifovich invariably went to sleep with a pistol under his pillow,” Starostin wrote in his book, ‘Football Through the Years’.

Once, when Vasily was out of Moscow, Starostin was taken away by the security services once more and placed on a train headed out of the city. Stalin brought him back to Moscow again, but Starostin was exiled to Kazakhstan soon afterwards for gross violation of passport regulations. He was supposed to have remained there for the rest of his life, but after the death of Stalin in 1953, he was rehabilitated and allowed to come back to Moscow.

How the Starostin brothers made a comeback in football

A monument to the Starostin brothers at FC Spartak Moscow's stadium

Valery Sharifulin/TASSAfter the death of Stalin, the remaining Starostin brothers were also released from their labour camps and rehabilitated. Pyotr decided not to return to football and became an engineer. Camp life had badly undermined his health: He had severe tuberculosis and had to have a leg amputated as a consequence of frostbite injuries. Pyotr died in 1993 aged 83.

The other three went back to their favorite sport and were involved in it until the end of their lives. Andrey became manager of the USSR national team and Alexander was chairman of the RSFSR Football Federation. Both died in the 1980s.

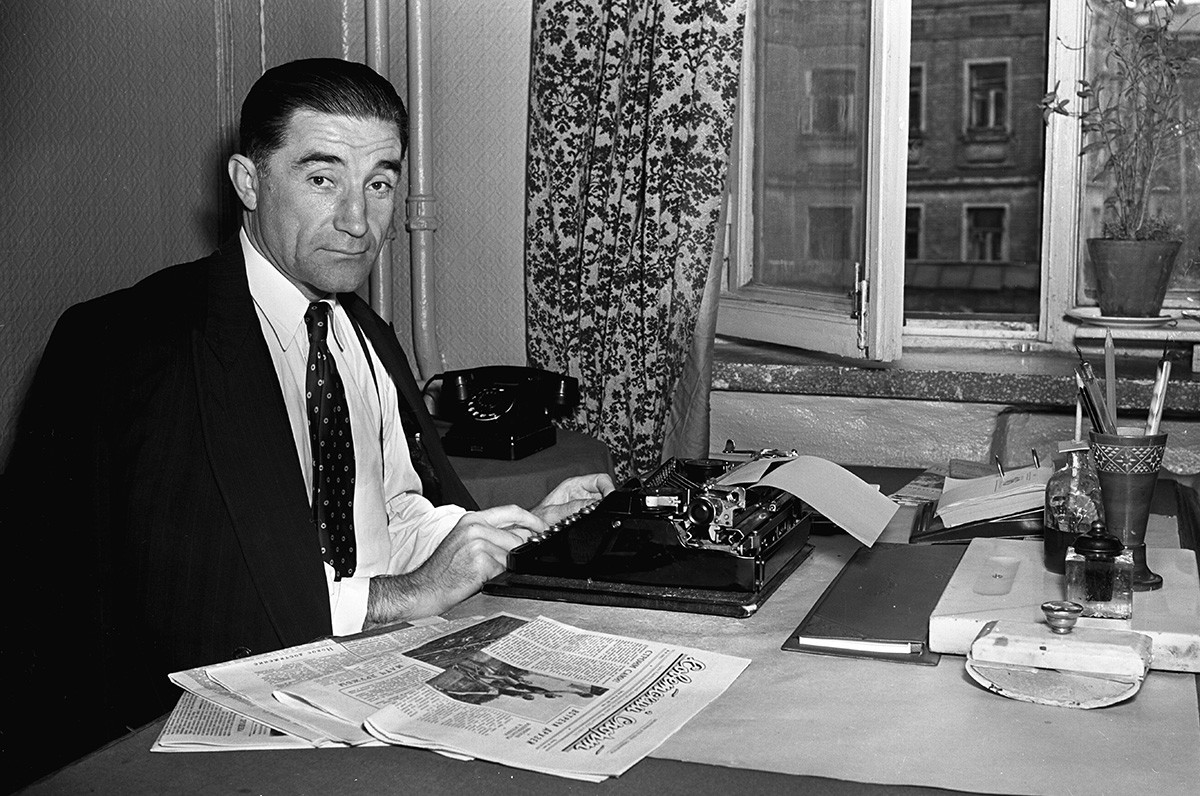

Andrey Starostin in 1957

Vasily Malyshev/SputnikAs for Nikolai, he went back to his old Spartak team, became president of the entire Spartak sports society and remained in this post until 1992. After the fall of the USSR, Nikolai managed to contribute to the establishment of the Russian Professional Football League. He lived to the age of 93, dying in 1996, after carving out an enduring place for himself in history as one of the most prominent figures in Soviet and Russian football.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox