How Soviet hydrogen bomb inventor Andrei Sakharov became a crusader for human rights

Andrei Sakharov at the Congress of People's Deputies of the USSR in 1989.

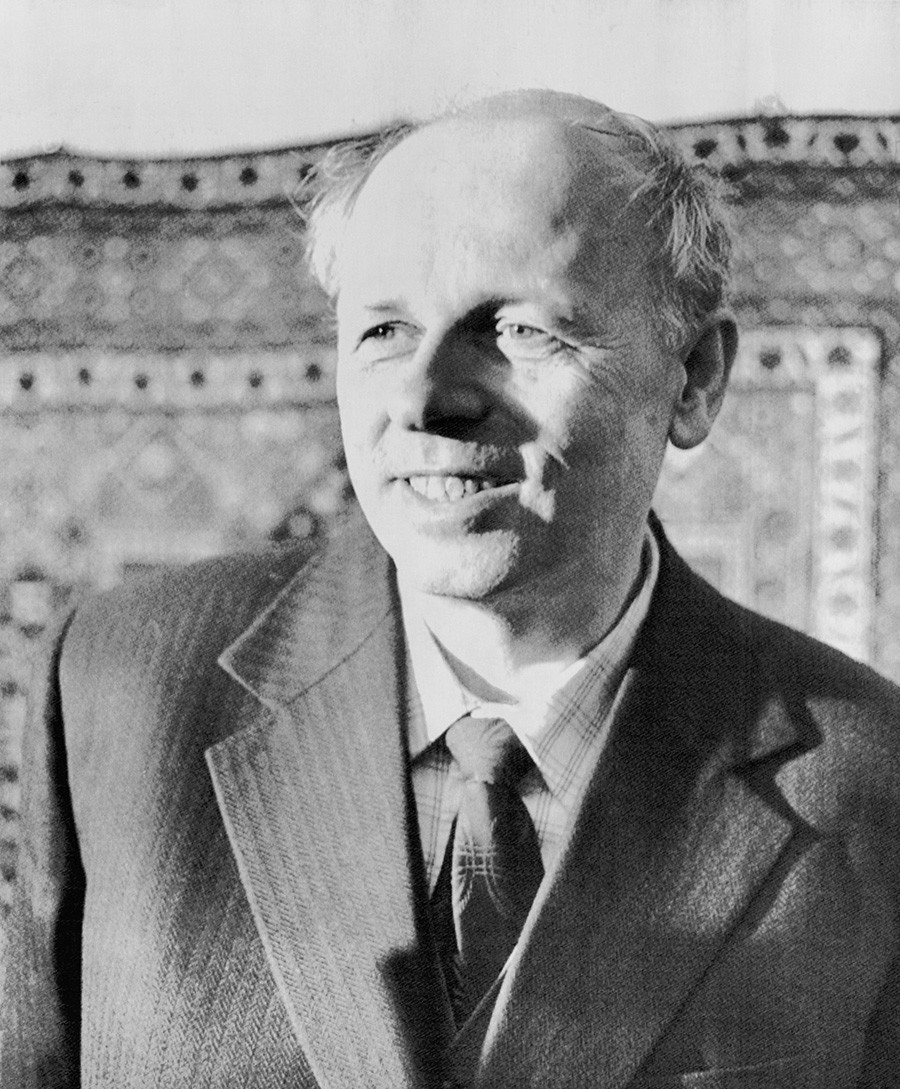

Sergey Guneev/SputnikAndrei Sakharov (1921-1989) became a household name in the USSR, first and foremost, as a man who created the nuclear bomb to ward off the threat posed by the United States.

Sakharov’s path to public life was as complicated and thorny as the laws of physics. Andrei followed in his father’s footsteps when he became a physicist.

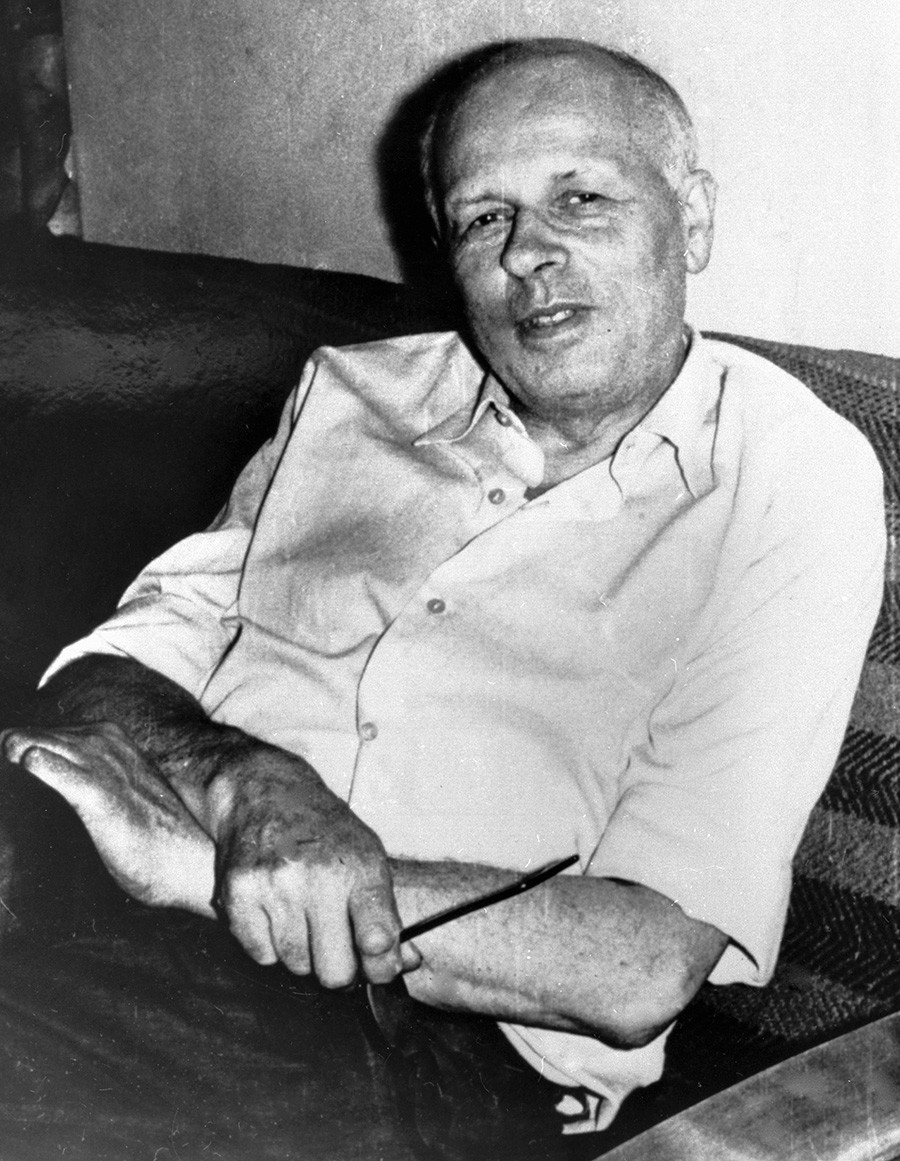

Sakharov had a lot of goals and never stopped working.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesA rare combination of intelligence and intuition, Sakharov graduated from the physics department of Moscow State University and was accepted into the Academy of Sciences at the age of 32 to become its youngest ever member. Unlike most of his peers, the unorthodox young scientist refused to join the Communist Party, even though, in those times, one needed to be a member of the Party to build a successful career.

In 1948, Sakharov became a member of the team developing the hydrogen bomb, headed by prominent Soviet physicist Igor Tamm. This would be Sakharov’s job and a mission to accomplish for the next two decades.

A brilliant theoretical physicist, Sakharov proved himself as an outstanding inventor. He made waves when he proposed an innovative design of a hydrogen bomb that would come to be known as the Sloika (‘Layer Cake’). Sakharov’s signature scheme featured layers of deuterium and uranium placed between the fissile core of an atomic bomb. In 1950, the Soviet scientist started work at the Scientific Research Institute of Experimental Physics, aka the Arzamas-16 secret nuclear facility. The group burned the midnight oil and their hard work paid off with the successful test of the first Soviet ‘Layer Cake’ hydrogen bomb on August 12, 1953. For his extraordinary achievements, Sakharov received three ‘Hero of Socialist Labor’ highest civilian awards.

A brilliant theoretical physicist, Sakharov proved himself as an outstanding inventor.

SputnikSakharov had a lot of goals and never stopped working. The group of researchers, led by him, continued their development work on improving the hydrogen bomb. On a parallel track, Sakharov, together with Igor Tamm, put forward the idea of magnetic plasma confinement and carried out an engineering analysis of installations for controlled thermonuclear fusion. In 1961, Sakharov proposed using laser compression for a controlled thermonuclear reaction. His breakthrough ideas laid the foundation for large-scale research in thermonuclear energy.

Human rights concerns

Diving deeper and deeper into his research, Sakharov began to question the ethics of developing weapons of mass destruction.

In the late 1950s, Sakharov became involved in human rights work.

Ullstein bild/Getty Images“Personally, I am convinced that humanity needs nuclear energy. It must progress, but only with absolute security guarantees,” he believed.

In the late 1950s, Sakharov became involved in human rights work. In 1958, two of his articles were published, warning of the harmful effects of the radioactivity of nuclear explosions on heredity and, as a consequence, on average life expectancy.

In the same year, Sakharov tried to advocate for an extension of the moratorium on nuclear testing declared by the Soviet Union.

READ MORE: The Soviets planned to wipe out the U.S. with a huge tsunami. How?

In 1961, Sakharov called on Nikita Khrushchev to stop nuclear weapons tests. The opinionated Soviet leader fired back that scientists should know their place and stay away from politics. In 1963, the Soviet Union and the United States finally agreed to such limits in the breakthrough Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty.

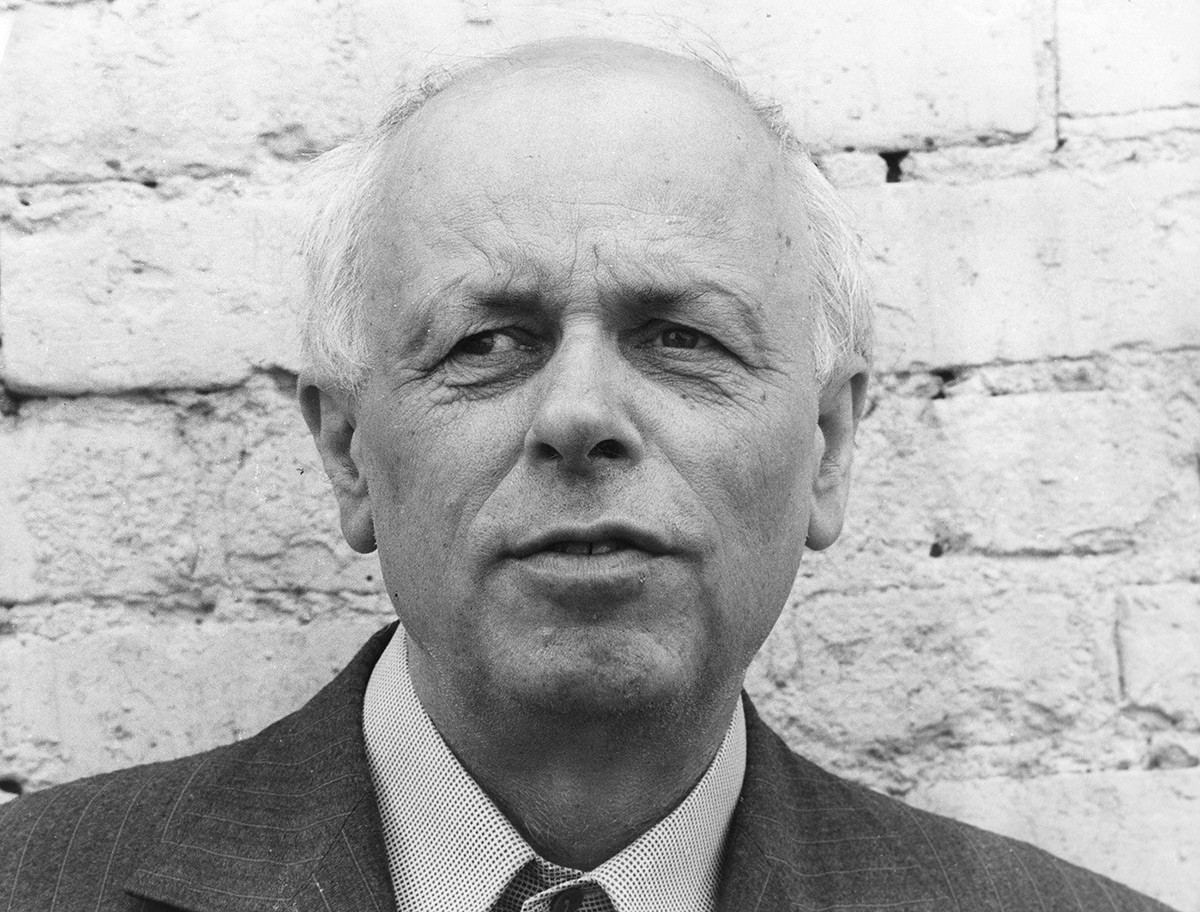

Sakharov’s path to public life was as complicated and thorny as the laws of physics.

Мalentin Kuzmin, Valentin Sobolev/TASSIn 1966, a staunch critic of Stalin’s cult of personality, Sakharov signed a letter to the 23rd Congress of the Communist Party against the rehabilitation of the merciless Soviet architect of large-scale purges.

In 1968, Sakharov penned an essay, aptly entitled ‘Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence, and Intellectual Freedom’. The text circulated in samizdat form before being published outside the Iron Curtain, in The New York Times. Condemning the nuclear arms race, Sakharov called for nuclear arms reductions and urged cooperation between the Soviet Union and the United States, advocating collaborative efforts of the two sides to combat the global threat of hunger, overpopulation and environmental pollution. Shortly after, Sakharov’s prophetic essay was translated into 17 languages, with over 18 million copies in circulation worldwide. Sakharov’s groundbreaking ideas were gaining more and more support.

READ MORE: Andrei Sakharov: 'Nuclear war might come from an ordinary one'

The publication of the far-reaching text cost Sakharov his job. He was removed from his responsibilities at the Arzamas-16 scientific research facility. In 1969, he returned to the Lebedev Institute of Physics in Moscow to work as a senior research scientist.

The extraordinary boldness of Sakharov’s human effort just knew no limits.

Anatoly Morkovkin/TASSSakharov was no slowpoke. He eventually gave up his attempts to change the fossilized minds of the Soviet leaders and began to appeal to those who, in his opinion, were ready to listen. Sakharov’s messages were honest, clear and direct and were aimed at ordinary people.

In 1970, Sakharov co-founded the Moscow Human Rights Committee. The scientist spoke out for the abolition of the death penalty, for the right to emigrate and against the compulsory treatment of dissidents in psychiatric hospitals.

In 1971, he addressed the Soviet government with a memorandum on urgent issues of domestic and foreign policy (Sakharov came up with proposals for the liberalization of the country) and, in 1974, he published an article abroad titled ‘The World in Half a Century’, in which he reflected on the prospects of scientific and technological progress and outlined his vision of the structure of the world.

In 1975, Andrei Sakharov wrote a book about the dangers of totalitarianism, economic stagnation and repression of ethnic minorities, entitled ‘My Country and the World’. In the same year, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for “fearless personal commitment in upholding the fundamental principles for peace”.

According to the Nobel Committee, the Soviet nuclear physicist “uncompromisingly and with unflagging strength fought against the abuse of power and all forms of violation of human dignity”.

Andrei Sakharov with his wife Yelena Bonner.

Vladimir Fedorenko/SputnikSoviet authorities banned Sakharov from traveling to Oslo, so his wife and partner for life Yelena Bonner had to pick up the award on his behalf.

“Now and forever, I intend to hold fast to my belief in the hidden strength of the human spirit,” Sakharov vowed in 1975.

Exile and fight for freedom

The extraordinary boldness of Sakharov’s human effort just knew no limits.

In December 1979, Sakharov slammed the decision to send Soviet troops to Afghanistan. He publicly voiced his criticism in an interview with the New York Times. Shortly after, he was deprived of all state awards and deported from Moscow.

Andrei Sakharov had spent seven long years in internal exile in the city of Gorky (now Nizhny Novgorod), with KGB agents keeping close tabs on the scientist 24/7.

By the time Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, Sakharov had become a symbol of Soviet oppression, the last man standing.

Andrei Sakharov made his reputation as the father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb.

Yuryi Abramochkin/SputnikOn December 19, 1986, despite the fierce opposition of his Politburo comrades, author of the policies of glasnost and perestroika Mikhail Gorbachev personally called Sakharov and told him that he had been released from exile and could continue his “patriotic work” in Moscow.

Things began to click at long last. Sakharov’s return marked a shift in attitude towards dissidents in the Soviet Union. To the surprise of many, Sakharov was elected to the newly created Congress of People’s Deputies.

One of Sakharov's major appeals was to abolish Article 6 of the Soviet constitution.

Valery Khristoforov; Igor Zotin/TASSDespite his deteriorating health, things that the outspoken scientist could say from the podium couldn’t be said by any other political activist. Tens of millions of people in the USSR listened with awe and respect to Sakharov, his voice never rising as he shared his fears and concerns.

“I am not a professional politician and maybe that’s why I am always tormented by questions of expediency and the final result of my actions. I am inclined to think that only moral criteria combined with an impartiality of thought can serve as a kind of compass in these complex and contradictory problems,” Sakharov once stated.

His moral compass vibrated like a tuning fork and never failed him. One of his major appeals was to abolish Article 6 of the Soviet constitution on the monopoly of the Communist Party on the domestic political arena. It only happened a decade later, in 1990, when an equality of all political parties was finally declared. Sadly, Andrei Sakharov didn’t live to see it, like so many other things.

Tens of thousands of Soviet citizens came to bid farewell to Andrei Sakharov in 1989.

Andrei Solovyov/TASSThe nuclear physicist-turned-human-rights-activist died of a heart attack on December 14, 1989, at the age of just 68. Tens of thousands of Soviet citizens came to bid farewell to one of the greatest 20th century fighters for human rights. His funeral turned into something more like a demonstration of what Sakharov had always stood for – freedom and human dignity.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox