The YOUNGEST Soviet pilot in WWII (PHOTOS)

Tens of thousands of children took part in the most brutal and bloody conflict in the history of humankind - World War II. Of course, minors were not called up and mainly worked in factories on the home front producing ammunition. However, there were those who were so desperate to fight the enemy that they ran away from home and managed to make their way to the front.

In the armies of the warring nations and in partisan detachments, children were mostly employed in carrying out household chores away from the front line. That said, there were cases when they managed to take part in reconnaissance raids, ambushes and acts of sabotage, as well as in real battles.

Many teenagers served as infantrymen, carriers of shells, sniper guns, while some even managed to master such complex hardware as a military aircraft. For instance, having forged his birth certificate, 14-year-old Englishman Tom Dobney joined a pilot school and, a year later, was flying a Royal Air Force night bomber. He managed to take part in 20 sorties before his deception was exposed.

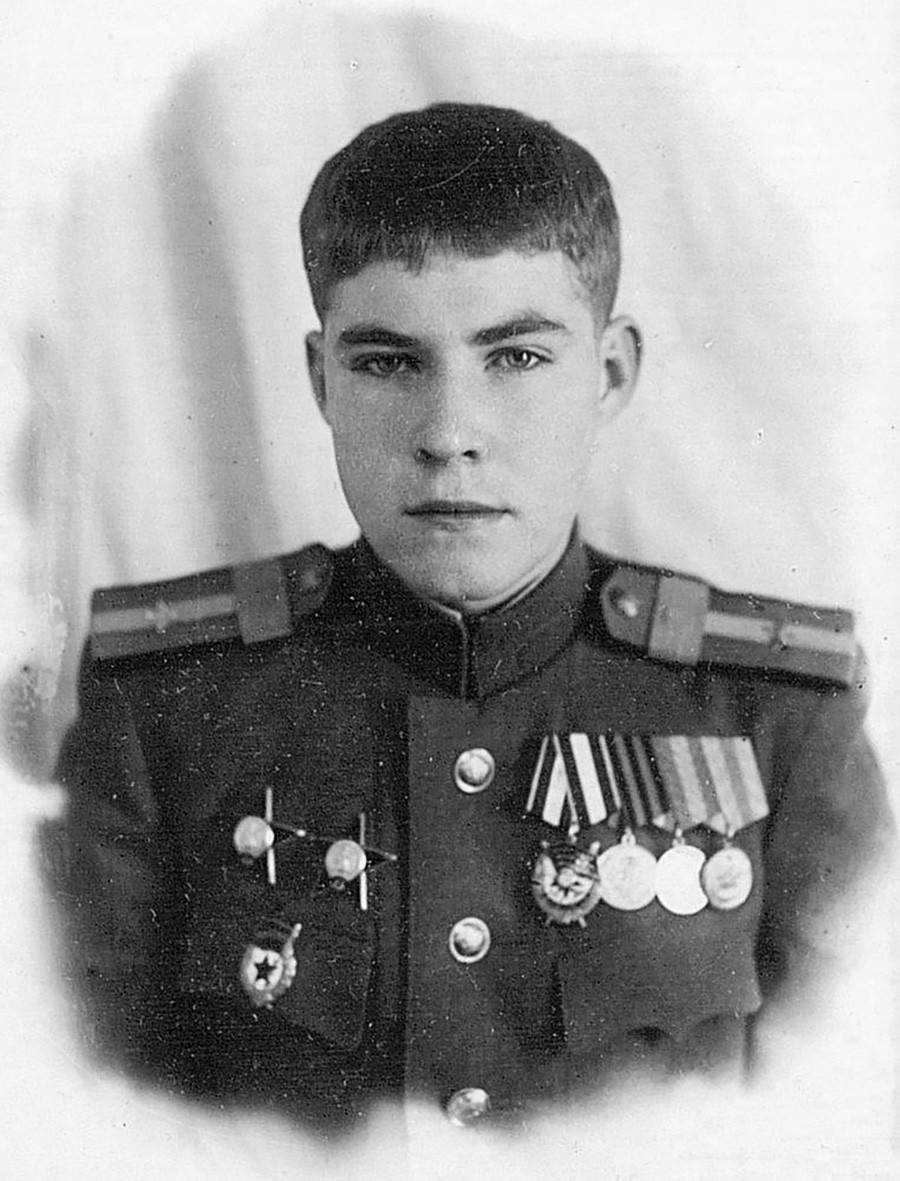

Arkady Kamanin.

Public DomainThere was a similar case in Soviet aviation, too. Except that 14-year-old Arkady Kamanin did not have to deceive anyone in order to become the youngest pilot in the Red Army Air Force.

Dreaming of the sky

Arkady was the son of the famous military pilot Nikolai Kamanin, who became one of the first Heroes of the Soviet Union for rescuing the crew of the Chelyuskin steamer that sank in the Arctic ice in 1934. So, it is not surprising that the boy was obsessed with aviation from childhood.

As a family of a military man, the Kamanins often moved from garrison to garrison in different parts of the country and everywhere they went, the first place than Arkady ran to see was the local airfield, where he spent all his free time and sometimes also the time that he was supposed to be spending in school. “Back in Central Asia, in the first year of the war, he spent days at the hangars. At the time, it seemed to me the most natural thing in the world: what teenager would walk by indifferently at the sight of real airplanes?” Nikolai Kamanin wrote in his memoirs titled ‘Pilots and Cosmonauts’.

By the age of 13, the boy became so well-versed in the mechanics of how aircraft worked that he was allowed to work in aircraft repair shops. “Together with the others, he repaired holes, cleaned parts, repaired damage, replaced units. He worked in hot and cold weather, in rain and slush,” his father recalled, not without pride.

Arkady with his father.

Public DomainIn 1942, Central Asian Military District aviation commander Nikolai Kamanin was transferred from Tashkent to the Soviet-German front. In early 1943, the family insisted that he take them with him.

At the new place, 14-year-old Arkady joined the Red Army, becoming a special equipment mechanic for the headquarters communications squadron. However, that was not enough as he dreamed of becoming a pilot.

Seeing his enthusiasm, the pilots undertook to train Kamanin Jr.: first they allowed him to taxi on the ground, then to fly a plane horizontally, performing simple maneuvers. The teenager turned out to be extremely capable: Soon, he learned how to take off and land and could perform complex aerobatics.

Finally, the question arose of allowing Arkady to fly independently. Of course, he was still too young for a high-speed fighter or an attack aircraft, but the U-2 (Po-2) low-speed multipurpose biplane, which the Red Army Air Force used as communications and reconnaissance aircraft and night bombers, was a perfect fit for him.

Arkady Kamanin and Nikolai Kamanin.

Public DomainThe examiner assessing the young pilot was Major General of Aviation Kamanin Sr. himself, whom his colleagues referred to as ‘Kamenny’ (Rus: “made of rock”), so exacting and strict he was. After a thorough grilling, he, nevertheless, allowed his son to fly and, in July 1943, 14-year-old Arkady was appointed a pilot with the 423rd Separate Communication Aviation Squadron.

Feats in the sky and on the ground

At first, Arkady flew on assignments to the headquarters of the air army and to the front headquarters. When he once managed to skilfully escape from a Messerschmitt that was pursuing him, he was allowed to fly to command posts on the front line and to partisans’ detachments behind enemy lines.

During one of his missions, Kamanin Jr. spotted a downed Il-2 attack aircraft in no-man’s land. Having landed next to the plane, Arkady, a slim teenager that he was, nevertheless managed to drag the wounded pilot together with his photographic equipment and filmed classified material into his Po-2 and take him to hospital. For this incident, he was awarded an Order of the Red Star.

In 1944, Kamanin once again showed his worth during the defense of the front headquarters from an attack by nationalists’ units of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (recognized as a terrorist organization in Russia). Having managed to take off under fire, he began to pelt the enemy with hand grenades. His courage was recognized with a second Order of the Red Star.

By the end of the war, 16-year-old Arkady Kamanin was already an experienced pilot with 650 sorties under his belt. In addition to two Orders of the Red Star, he was awarded an Order of the Red Banner, as well as medals “For the Capture of Budapest”, “For the Capture of Vienna” and “For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945”.

“Arkady flew a lot, with youthful recklessness and enthusiasm,” Kamanin Sr. wrote about his son. “He served honestly, strictly observed discipline and, of course, dreamed of seeing himself as a pilot of a real Il-2 combat aircraft.”

Unfortunately, the dreams and hopes of the youngest Soviet pilot were not to come true. Having survived World War II, Arkady Kamanin died of meningitis in 1947 at the age of just 18.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox