How a junior officer became supreme commander of the Russian army

On Nov. 22, 1917, something unheard-of took place in the Russian army. For the first time in its history, it was headed not by the emperor or a general, but by a junior officer – a lowly ensign (praporshchik). But Nikolai Krylenko was appointed commander-in-chief by Vladimir Lenin not to lead Russia to victory in WWI. Far from it. His task was to get the country out of the conflict as quickly as possible.

The road to power

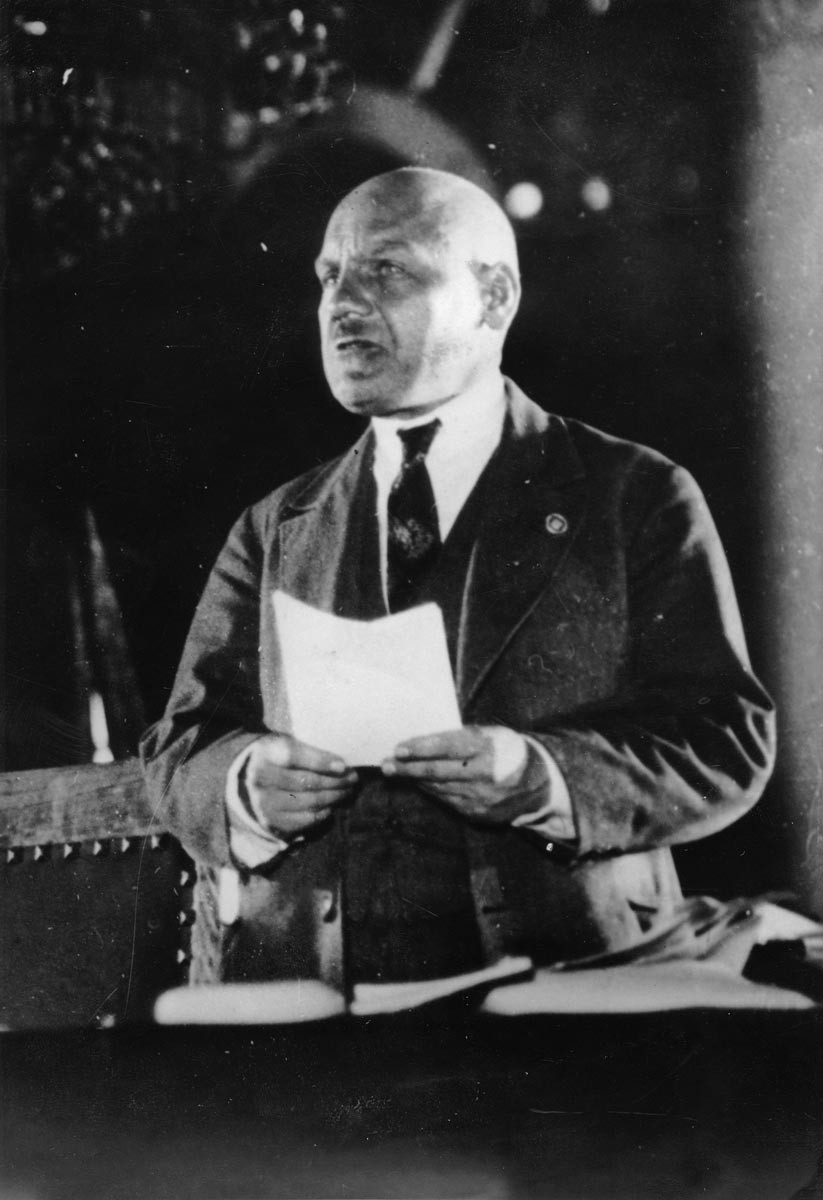

Nikolai Krylenko.

SputnikKrylenko was never a genuine military man, nor did he claim to be. A university graduate (in history, philology and law), before the war he was drafted for a year’s military service in the infantry regiment of the city of Lublin (present-day Poland, then part of the Russian Empire). After graduation, he was promoted to the rank of ensign in the reserve.

Krylenko’s true calling was the revolutionary struggle. In 1904, aged 19, he joined the Bolsheviks and was soon active in propaganda and agitation, taking part in rallies and distributing underground newspapers, all the while playing cat and mouse with the Russian secret police. “A professional revolutionary... an outstanding lawyer... a brilliant publicist... a talented speaker,” is how one of Lenin’s closest associates, Vasily Vasiliev, described Krylenko.

In 1915, when WWI was in full swing, Krylenko was arrested as a draft-dodger. The following year, however, he was released and sent to the Southwestern Front as a liaison officer. Even there Krylenko continued his propaganda activities, calling for an immediate end to the war.

The more Russia plunged into revolutionary chaos, the higher Krylenko rose. When elective political organizations (so-called soldiers' committees) began to spring up in the rapidly disintegrating army, he invariably was at their forefront. Having played an active role in the Bolshevik coup d’etat, Krlyenko became a member of the first Soviet government, the Council of People’s Commissars, responsible for army and navy matters.

Army chief

To retain power, the Bolsheviks understood well the importance of pulling Russia out of WWI. Hence, their first legislative act was the Decree on Peace, adopted Nov. 8, 1917, inviting “all belligerent nations and their governments to begin immediate negotiations on a just and democratic peace,” to be concluded without annexations and indemnities.

Although the decree was ignored by the belligerent powers, Lenin instructed the supreme commander, General Nikolai Dukhonin, to begin peace negotiations with the enemy. The latter refused and was promptly dismissed from his post on Nov. 22 “for disobeying the orders of the Government and for conduct resulting in unprecedented adversity for the working masses of all countries, and especially the armies.” Ensign Nikolai Krylenko was appointed as his replacement that very same day.

Nikolai Krylenko in 1918.

Public Domain“This appointment marks the pinnacle of disgrace for the Russian army,” wrote General Alexei Budberg, who later figured prominently in the White movement in Siberia: “The first directive of the new Supreme Command... was a [radiogram] ordering ‘each regiment to independently conclude a truce in its zone.’ All the military, political and intellectual ineptitude of that bastard streamed out of this directive. He didn’t have the brains to understand that there was a real army on the other side of the front, that any truce proposal would be rejected out of hand.”

Nevertheless, Krylenko fulfilled the task of extracting Russia from the war. In early December, relative calm descended on all fronts, and peace negotiations between the Soviet delegation and representatives of the Central Powers commenced in Brest-Litovsk.

On Dec. 3, he arrived in Mogilev (present-day Belarus) at the Supreme Command Headquarters to arrest “enemy of the people” Dukhonin. The general did not get to face trial. Despite Krylenko’s protests, a crowd of angry sailors burst into the carriage where he was being held and bayoneted him to death. During the Russian Civil War, the expression “to dispatch to Dukhonin’s headquarters” became a metaphor for execution without trial or investigation.

Lawyer, chess player, climber

People’s Commissar (Minister) of Justice of the USSR Krylenko during one of the court session.

Getty ImagesSoon after the conclusion of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918, which marked Russia’s withdrawal from WWI, Krylenko tendered his resignation to Lenin as supreme commander. The former ensign had decided to return to his main profession of lawyer, ultimately becoming one of the founders of the Soviet legal system.

During the Russian Civil War, he headed the extraordinary courts of justice (revolutionary tribunals), later acted as a state prosecutor in Stalin’s show trials, and served as prosecutor of the RSFSR and as People’s Commissar (Minister) of Justice of the USSR. With Krylenko’s direct participation, the legal foundations of the mass repressions of the late 1930s were laid, and the practice of political arrests and extrajudicial persecution became widespread.

At the same time, Krylenko became the “father of mountaineering” in the USSR, having achieved its recognition as a sport at the state level. He not only organized mountaineering expeditions to the Pamir Mountains in Central Asia, but took an active part in them. “Mountains are treacherous and dangerous, but they can be conquered if one does not retreat in the face of hardship... It requires continuous mental training, dexterity and courage. Isn’t it the perfect school for future soldiers, Red commanders?” he philosophized.

Krylenko in 1937.

Getty ImagesNikolai Krylenko also played a significant role in the popularization of chess. Not only did he head the Soviet Chess and Checkers Association, but served for 14 years as the editor of a specialized chess magazine and arranged several international tournaments in Moscow, attended by the world’s top players.

It was a rule of thumb in Stalinist Russia that the purgers ended up being purged themselves. Nikolai Krylenko was no exception. In 1938, at the height of the Great Terror, he was arrested on charges of anti-Soviet activity and summarily executed. He was posthumously rehabilitated in 1955 for lack of corpus delicti.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox