How the Russian ambassador saved Beijing from British and French troops

In the mid-19th century, the Qing Empire had seen better days: the country was in the grip of the Taiping Rebellion, a massive peasant uprising directed against foreign domination and the ruling Manchu dynasty. At the same time, during the two Opium Wars, China came under huge pressure from the Western powers seeking to increase their economic influence in the Middle Kingdom.

The better trained and armed forces of Britain and France easily defeated the Qing army, and by early October 1860 they were at the gates of Beijing, ready to ravage the Chinese capital. It was at this critical venture that the city was saved by the Russian envoy, Major General Nikolai Ignatiev, but not solely for the sake of the Chinese.

Carving up the Far East

Victims of the Second Opium War 1856-1860.

Public DomainThe Russian envoy was sent to China on an almost impossible mission: to single-handedly persuade the Chinese to fulfill the terms of the territorial division treaty previously signed with Russia.

By the mid-19th century, taking advantage of the weakness of its southern neighbor, Russia had significantly strengthened its positions in the Far East. In 1858, in the city of Aigun, it concluded an agreement with the Qing under which defined the border between the two empires along the Amur River as far as the Ussuri River. The issue of the boundary from the Ussuri to the Pacific coast was left for a later date was to be decided later.

Emperor Yizhu, however, soon backtracked on the Treaty of Aigun, and demoted the officials who had concluded it. The official line was that “the left bank was not ceded to Russian possession,” but “on loan” for the settlement of “poor Russians forced to roam due to land shortages.”

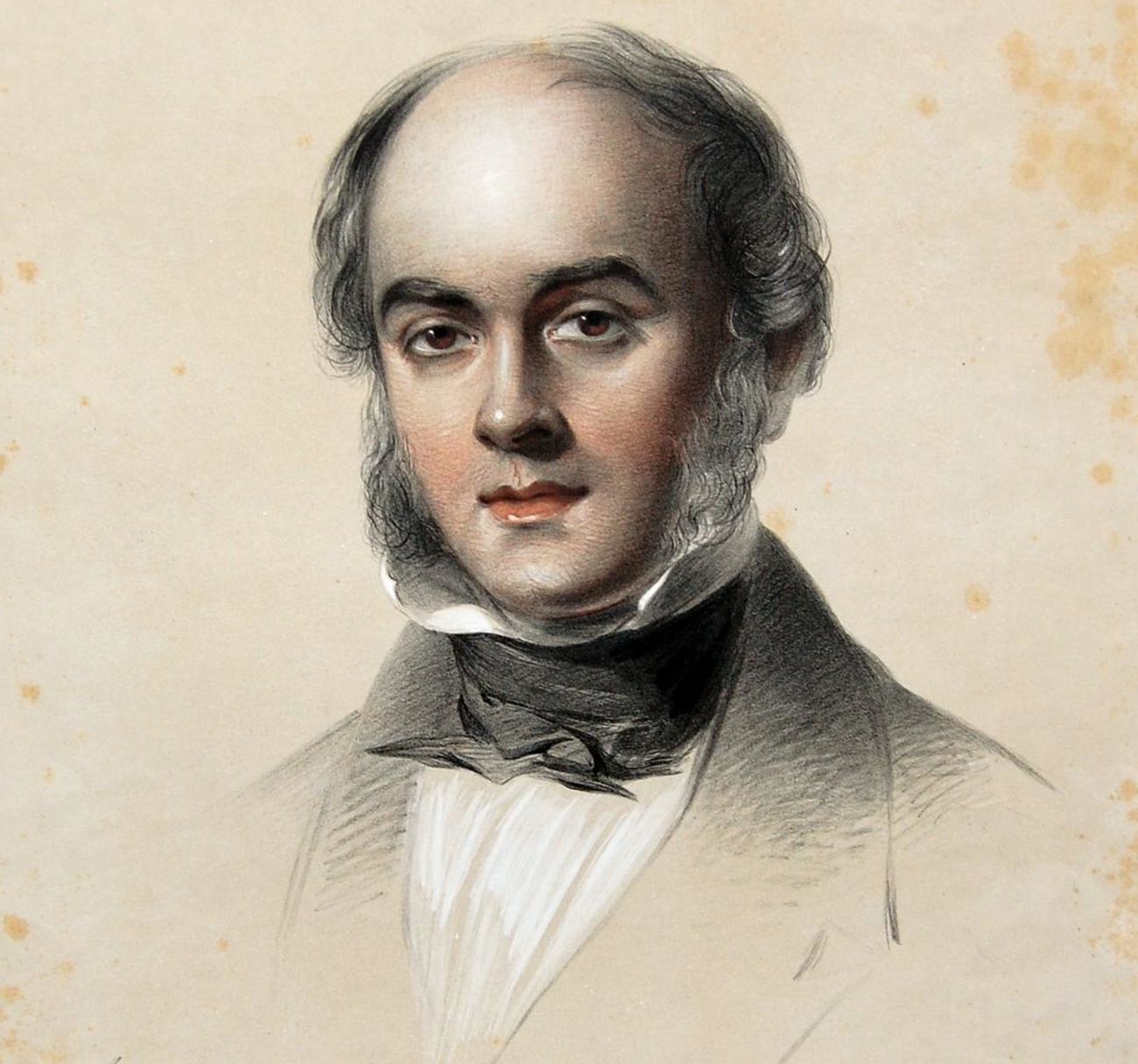

Emperor Yizhu.

Public DomainThe tsarist government, intent on finding a peaceful solution, dispatched Ignatiev to Beijing. He spent almost a year in the imperial capital endeavoring fruitlessly to achieve a final demarcation between the two states and recognition of Russia’s rights to the coastal territories, which de facto belonged to it.

In the end, Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Gorchakov proposed the following plan to his envoy: make contact with the British and French troops and go with them to Beijing, where he would as a mediator and peacemaker, demanding the ratification of the Treaty of Aigun as a reward from the Qing.

The art of diplomacy

In May 1860, Ignatiev made a secret journey from the Chinese capital to the French and British camp at Shanghai, where he made the acquaintance of Baron Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros and Count James Bruce, who had been tasked by Paris and London, respectively, to secure the Qing’s submission and the right to freely trade opium in China.

Nikolai Ignatiev.

Dmitry YanchevetskyInitially, the diplomats were suspicious of the Russian general, but he quickly dispelled their qualms. Ignatiev misled them by stating that all territorial disputes between the Russian and Chinese empires had been resolved, and he was there only as a peacemaker.

Ignatiev thus gained the trust of the allies, becoming for them a valuable source of knowledge about China, which they tapped repeatedly. He provided them with vital statistical and topographic data, biographical details of Qing officials, and even a city plan of Beijing.

What’s more, Ignatiev also won Chinese hearts and minds. The Russian mission purposely lagged a little behind the British and French troops, assisting inhabitants who had suffered at the hands of the European soldiers and holding meetings with local authorities and traders. “It is remarkable how the villages that lay along the banks of the river greeted [us] as deliverers, as soon as they recognized that the ship was Russian, seeing [us] as peaceful and supportive of China, and pleading for protection from the allies who were robbing and destroying them...” recalled Ignatiev.

Portrait of James Bruce.

Public DomainBy early October 1860, when the British and French troops reached Beijing, Ignatiev had come to be respected equally by both opposing sides. His help came in handy at the critical moment.

Saving the city

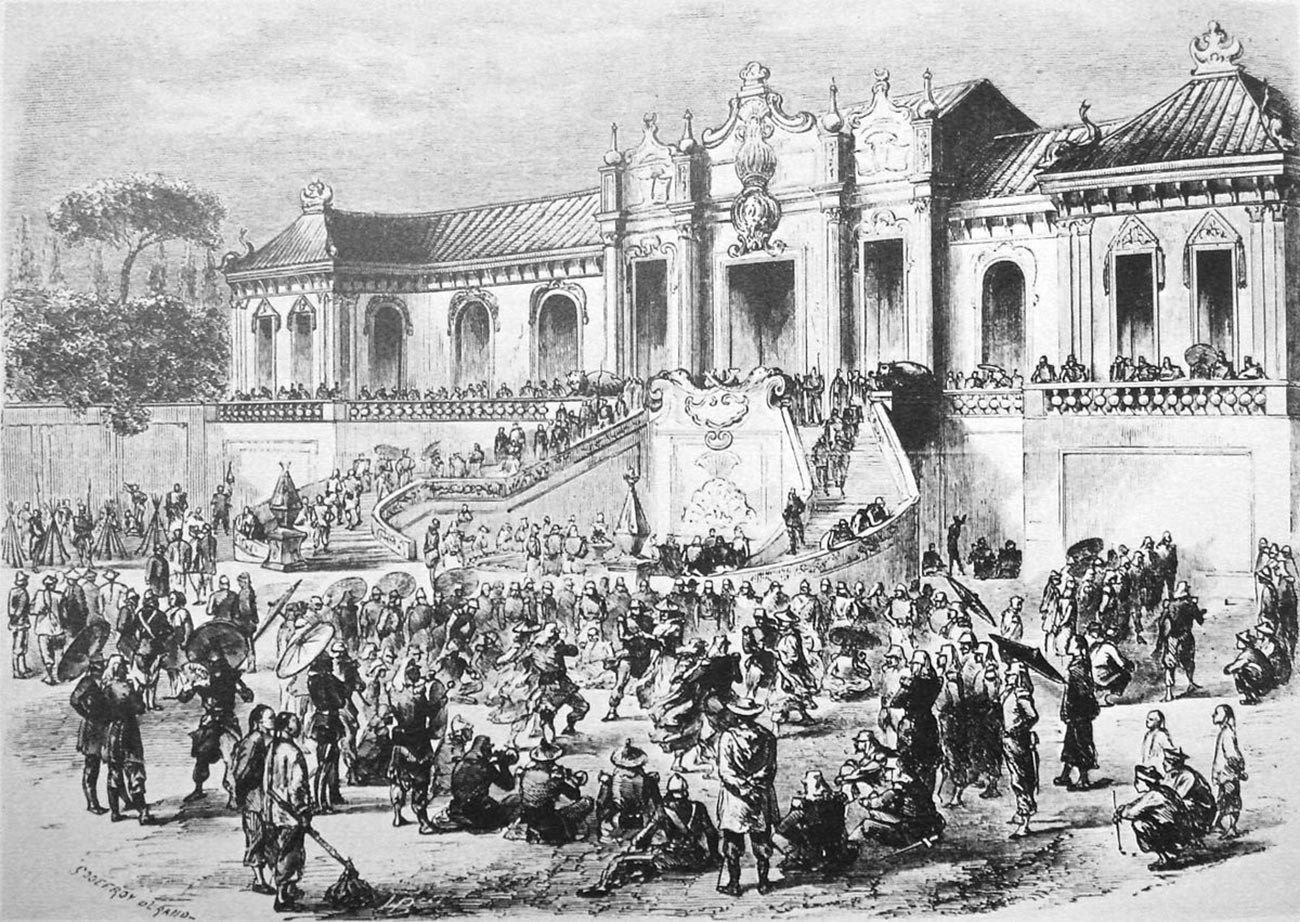

After the negotiations between the allies and representatives of the Qing government broke down, some of the Anglo-French expedition force fell into the hands of the Chinese and, after prolonged torture, were executed. The enraged Europeans retaliated by seizing and looting the emperor’s summer residence, Yuanmingyuan Palace, forcing its occupant to flee the city.

Beijing was a hair’s breadth away from being plundered on a massive scale when the monarch’s half-brother and already de facto ruler, Prince Gong, turned to Ignatiev as a mediator. The Russian general agreed, but imposed a number of conditions: ratification of the Treaty of Aigun and the demarcation of the border along the Ussuri River as far as Korea.

Looting of the Yuanmingyuan Palace.

Public DomainHaving received consent, Ignatiev made every effort to halt the offensive and establish a dialogue between the warring sides. “If the Qing dynasty falls, who will you sign a treaty with? Who will pay you war indemnities? Instead, you will have to set up a new power structure in China and incur new expenses!” he persuaded Gros and Bruce.

Eventually, having acquiesced to the Russian envoy, the British and French sat down at the negotiating table. After securing from the Chinese extensive trading privileges, including the legalization of the opium trade, they left the capital.

In gratitude for his assistance in resolving the crisis, the Chinese finally agreed to negotiate with Ignatiev. On November 14, 1860, the Convention of Peking (Beijing) was concluded, under which Russia received ownership the lands on the right bank of the Amur from the mouth of the Ussuri to the shore of the Pacific (in the east) and the border with Korea (in the south). “All this without bloodshed, solely through the skill, perseverance and self-sacrifice of our envoy...” noted Eastern Siberian governor Nikolai Muravyov-Amursky in a letter to Gorchakov.

Prince Gong of the Qing dynasty.

Public DomainThe document marked out the boundary between Russia and China, which, with some alterations, remains in place to this day.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox