What is the ‘Obshchak’, a fundamental part of the Russian criminal underworld?

Those growing up in the wild 1990s in Russia and other post-Soviet states remember how they were stripped of change and told it was meant to fill the obshchak. Few of the youngsters from whom the pennies were routinely collected understood what the mysterious obshchak was.

Yet, for the sharks of the criminal underworld, the obshchak made up a real, tangible and closely guarded fund aimed to finance their shenanigans.

‘Keeping the boys warm’

The Russian criminal underworld distinguishes between two types of obshchak — the term derives from the Russian word for “common” (Russian: obshchii) — depending on where the funds are collected and how they are being used.

Inmates in a Russian prison.

Shepard Sherbell/Corbis/Getty ImagesThe so-called “camp obshchak” (Russian: lagerniy obshchak) refers to a collective fund collected by inmates in any given prison in the country.

Depending on the prison, the size and contents of the camp obshchak vary. As a rule, the usual items that go into it are cash, cigarettes, tea and non-perishable food items like canned meat. Those are used to help the inmates in need or to buy small privileges provided by prison guards in exchange for cash.

The camp obshchak is replenished continuously from various sources. Inmates are expected to voluntarily donate a part of the parcels they receive from relatives and friends to the obshchak. Refusing to do so is frowned upon as an insult to the thieves’ culture and traditions and may be punishable by social ostracization or worse.

In prison, senior inmates may levy all card games in a prison with a tax of 20 percent or more. The money goes to fund the obshchak.

Sometimes, the camp obshchak may be replenished from the so-called “free cash desk” (Russian: svobodnaya kassa), a network of financial sources located outside of the prison walls and aimed at channeling a stable cash flow inside.

As it often happened in the 1990s, local seniors with ties to the criminal underworld coerced the youth to donate money to the obshchak, a practice known as “keeping the boys [read inmates] warm” (Russian: patsanov na zone gret’).

Another source of cash inflow to the camp obshchak is donations from rich and powerful thieves in law. A letter by notorious Russian mafia boss Vyacheslav Yaponchik to the inmates of one of the Russian prisons reads:

‘Tramps’ of the 16th BUR [slang for “max security wing within a prison colony”], I salute you wishing you only the Best and the Brightest - Vyatcheslav ‘Yaponchik’ here. Seeing as, today, one of you is going back out into the general pop, I’m sending over another 400 rubles… these 400 rubles - in agreement with other tramps - are to be deposited into the obschak, together with the previous 200 rubles: they were given to Ruslan as a thief, but this is not appropriate, as he is no thief. I think we’re clear here. So, I’m sending the money totalling 600 rubles back to the treasury. I’m doing alright. I thank you all for your attention and concern. Please accept my kindest regards. With respect - Vyatcheslav ‘Yaponchik’.

Reputed mafia godfather Ivankov is greeted by relatives as he leaves a court building in Moscow.

ReutersDespite donations and other sources of cash inflow, the camp obshchak looks like petty cash compared to its analog outside of the prison walls, the so-called free obshchak (Russian: svobodniy obshchak).

Millions of dollars

The story has it that the free obshchak was born at the beginning of the 20th century, although it is hard to tell for sure when high ranking criminal bosses started accumulating a centralized cash fund.

What is generally agreed upon is that the size of the free obshchak is enormous and can’t be compared to the petty size of even the most lavish camp obshchak as it is, by some estimates, measured in millions of U.S. dollars.

The financial schemes directed to replenish the free obshchak are also more elaborate. The cash flows from all sorts of criminals dealing in the country.

“Everyone pays tax to belong to the obschak: regular route pickpockets, purse snatchers, car thieves, drug dealers, house robbers and hucksters and loot repurchasers. A contribution to the common sum is called a share. The criminals regularly working in the region are required to pay 5-10 percent of the profits, depending on the value of the stolen goods. ‘Tourers’, car thieves and gang-bang car thief brigades may get taxed 15-20 percent for the right to work in their native region and disturbing the peace,” according to a popular YouTube channel dedicated to researching the Russian criminal underworld.

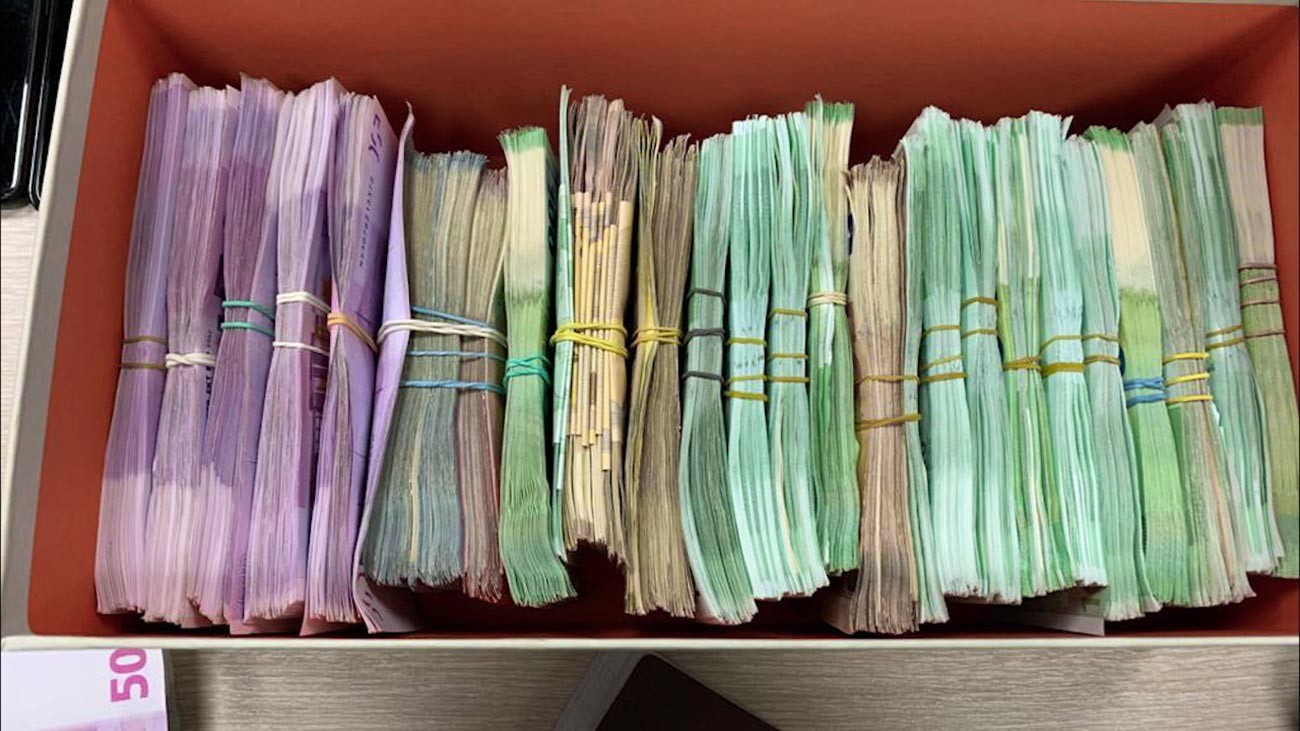

Although the free obshchak can exist in the form of a legalized financial structure, criminal bosses are believed to favor hard cash, as it is harder for the authorities to trace and arrest the money.

“A cashbox of this sort is guarded not by one or two people. According to some sources, the number of people guarding this obschak sometimes reaches 20 fighters, selected at a group meeting. Guarding the cashbox is an honorable and a profitable activity. The mission is trusted to fanatics, the type of thieves with the deepest loyalty to the thief-in-law principle,” claims the above-mentioned YouTube channel.

"The number of people guarding this obschak sometimes reaches 20 fighters, selected at a group meeting."

Antoine Gyori/Sygma/Getty ImagesThose who unlawfully encroach on the obshchak are said to be sentenced to death in most cases.

Although the destination of the money from the free obshchak cannot be known for sure, the fund is believed to be used to sponsor future criminal activities, support families of deceased mafia bosses, bribe state officials and keep the criminal underworld afloat, in general.

Despite the declared “noble” causes, however, some believe the spoils that the obshchak provides go to the few at the top of the criminal hierarchy. If so, donations to the obshchak should be viewed as a gesture of commitment and loyalty to the bosses of the criminal underworld, adherence to the social norms of thieves’ lifestyle and as a long-term investment by ambitious outlaws who aspire to eventually get to the top of the food chain.

Click here to find out who ‘thieves-in-law’ were, Russia’s violent mafia bosses.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox