What Russia felt IMMEDIATELY after the USSR’s breakup

State flag

This was the most noticeable of all changes: the red Soviet flag over the Senate Palace of the Moscow Kremlin was replaced with the Russian tricolor. This happened a mere 38 minutes after President Mikhail Gorbachev’s live televised address, in which he announced his resignation. However, that immediate change went almost unnoticed by regular people. The changing of the flag would only later become one of the greatest sources of worry for people.

The reason for that is because the lowering of the flag was carried out in the most mundane way - no TV crews were even invited to witness it. There were hardly any crowds on the Red Square that day and it was snowing and raining. “I managed to get only several shots, as it all happened so fast. One-two and the red flag was already down; then the workers raised the Russian tricolor. The historical changing of the flag took all of 10 minutes,” photojournalist Aleksey Boytsov remembered. He was among the few there to witness it.

Prices in stores

The country’s collapse also heralded the end of government-regulated pricing: the state practically no longer involved itself in price setting. The government called this liberation of pricing a necessary reform. The deficit that began taking on threatening proportions by the start of the 1990s, according to some sources, resulted in there being three times less goods on shelves than people had money. The government thought the reform would merely correct the supply and demand dynamic.

However, by the end of the year, many goods grew 8-11 times in cost, while, in 1992, it was already dozens of times more expensive. The people began referring to this as “shock therapy”. Prices could change several times in a day, which reduced the savings of many families to nothing.

Alcohol

In 1992, all limits on alcohol sales were finally lifted. The state monopoly on production was no more, while foreign brands were allowed to enter the market. The most prominent one for a while was that of German-made alcohol called ‘Royal’. A liter of pure alcohol cost 25 percent more than a liter of vodka, but people diluted it with water, so they got much more out of one bottle.

‘Royal’ immediately gained popularity for its tacky TV ad, its price and its availability; you could find it in every kiosk, as it became a symbol of the 1990s. “Endless ‘Royal’ ads existed in such quantities that I still remember it. As well as traffic cops’ weary reaction to the terrible stench emanating from cars they pulled over, as diluted ‘Royal’ would be used for windshield wiper fluid,” actor Yury Stoyanov recalled.

With the rise in popularity of imported alcohol came an increase in incidence of alcohol poisonings, which, by 1994, quadrupled from 1992. According to analysts, counterfeit alcohol accounted for 67 percent of all production.

‘Vremya’ TV news show intro

‘Vremya’ is Russia’s oldest and main show with the latest news on domestic and foreign developments. It used to air at 9 PM on Channel 1 and became somewhat of a national tradition. The intro would play to the tense music of composer Georgy Sviridov. It depicted the globe, most of which was painted red (the USSR didn’t mess around). A second later, a red star would launch from the western part of the country, similar to the ones you see over the towers of the Kremlin.

But when the gigantic country fell apart, the symbolism lost all meaning and the intro became another symbol of a bygone era. First, a politically neutral intro replaced it, depicting different landmarks across Russia, then one with shots of the newsroom took its place. The melody was the only thing that was left of the old ‘Vremya’.

New citizenship, but nonexistent country’s passport

Millions of people’s citizenship changed overnight. According to the new law, all citizens living in the newly-formed countries were officially their citizens. The Soviet passport, however, was valid until the 2000s - it was used for domestic business, as well as for foreign travel. The difference was that Russian citizens got their stamp in the Soviet passport, while non-Russians had also had the same Soviet passport, but without the stamp. The conditions were the same for them for another ten years or so: they could register marriages, births, positions in new workplaces and so on.

Soviet seal of approval

The quality of items purchased in the Soviet Union was guaranteed by a special seal - a reverse letter ‘K’ (from the Russian word for “quality” - kachestvo). It would only be given to those goods that were approved by a special commission, which oversaw the entire production process and controlled the quality standards.

It was that seal that was synonymous with quality that many had started to miss after 1991. With the seal no longer enforced, the market was flooded with foreign brands of unknown origin, with plenty of goods of questionable quality. Those missing the USSR still recall that a cheap price didn’t have to indicate low quality. By the way, things like Soviet cupboards and drawers still carry on serving many Russian families well to this day. People only get rid of them because they’re dated - not because they break.

Money

Money depicting Lenin was also replaced with the Russian ruble. The gigantic country was only given two weeks to transition and allowed to exchange 30,000 rubles (the deadline was extended to the end of the year, with the limit extended to 100,000). The process was further complicated by the fact that new banknotes could only be exchanged using a passport (which was stamped upon exchange) and could only be done once, according to place of registration.

A genuine panic gripped the nation. People lined up for days, searching for acquaintances with nothing to exchange, asking them for help with the process. Not everyone was successful, which resulted in them simply losing most of their savings.

“It was understood that the reform presented citizens with certain difficulties,” Central Bank head Viktor Geraschenko later explained. “But what else could you do? After it became clear that the unified ruble zone could not be sustained, the main order of business became the elimination of a massive stash of Soviet rubles from the economy of countries still belonging to CIS countries. Until then, they easily entered the domestic market, leading to deficits and price hikes.”

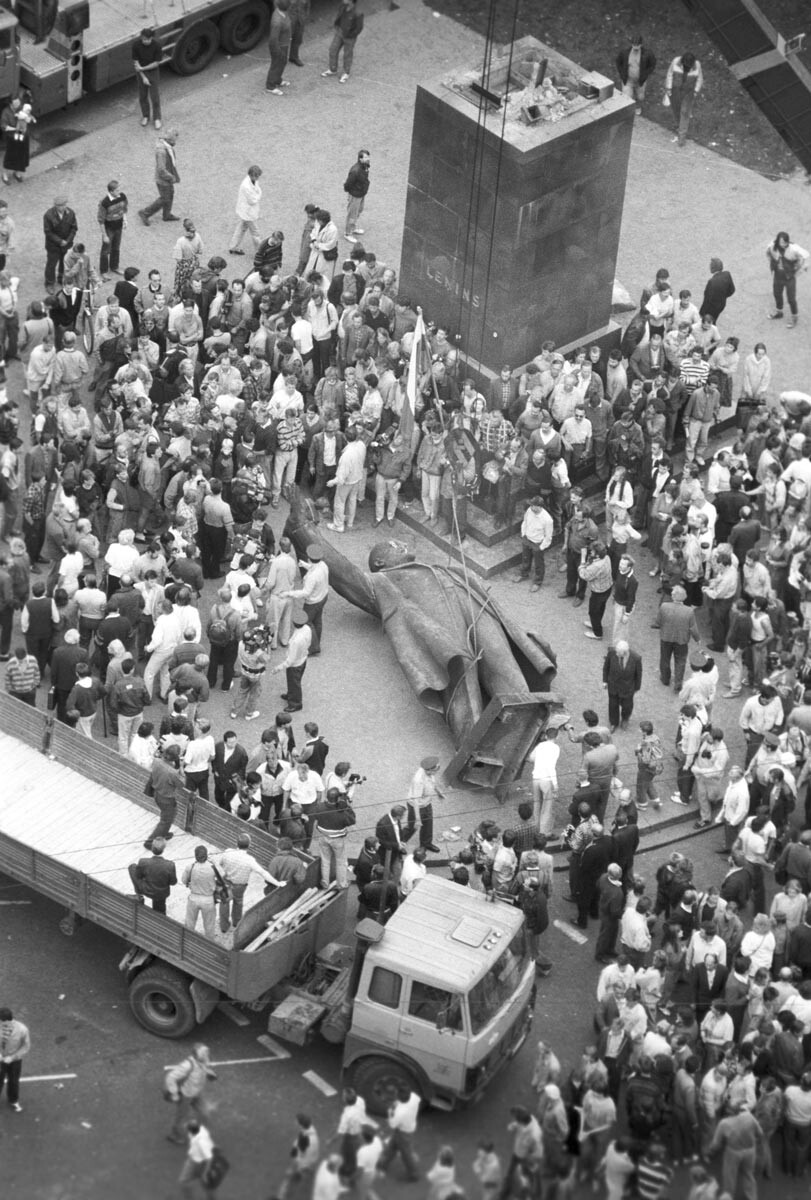

Lenin’s disappearance

Lenin’s name and image in the lives of Soviet citizens was unshakeable for six and a half decades after his death and until the collapse of the communist system. The main square of almost every city in the USSR would bear his name. This also included movie theaters, schools, stadiums, universities, train stations, cities and collective farms. Future ‘Pioneers’ respectfully referred to Lenin as “grandfather” and, for many, he indeed was like a family member, providing a watchful eye as they navigated life, looking down at them from portraits and statues everywhere.

With the breakup of the Soviet Union, all that changed abruptly. The Lenin name began to disappear from names of books, articles, dissertations and so on. The school and college system also began to be reformed. The apogee of de-Leninization occurred in 1993. As historian Yury Pivovarov notes, the media began seeing Lenin as the embodiment of absolute evil. Although, in the new Russia itself, this process of dismantling the personality cult took on a more immaterial character.

“All these metamorphoses predominantly took place in publishing, on TV and the radio… the dismantling of Lenin happened only verbally and almost didn’t materialize in any other way,” Pivovarov notes. The taking down of monuments was carried out selectively, while there was no real mass removal of his likeness taking place - something that couldn’t be said of former Soviet republics, where a move away from Soviet symbolism became a matter of acute importance, starting even before the dissolution of the USSR. The first monument was dismantled in 1990 in modern-day Chervonograd, Ukraine.

VHS rentals

There weren’t all that many foreign movies that Soviet people had access to, but with the fall of the Iron Curtain that all changed. First, the people started getting VCRs; second - the world of Western cinema was now open to them, thanks to VHS tapes. The first video rentals had also appeared, renting out pirated copies that all featured the same hilarious dubbing.

At the time, these rental spots were a sort of small corner somewhere in a big department store or even a barber shop. They all had fat notebooks where you could check out what was available. You paid a sort of bond payment (the price of the tape), the rental fee and the guy would enter your name into the book with the return date. Those that failed to return the tapes on time would face penalty fees. Disney and bloody Hollywood action movies proved most popular and created a massive demand among the public.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox