How to rob a home in the Soviet Union

To get to the nitty-gritty of the ‘art’ of burglarizing – as it was practiced in the Soviet era, let’s hand it over to a former professional. The methods he describes might surprise you.

“I began working ahead of time, a month in advance,” an elderly home burglar from St. Petersburg told me. “You had to have some funds in order to buy out the tickets to an entire group compartment aboard a train – say, one headed south, to Sochi. The performance would start on the day of the departure. I’d appear at the ticket office running, seemingly out of breath, looking for the right ‘clients’ – for example, a family with a child that already has tickets to a group compartment in my train carriage. Then comes the spin.

People in a Soviet railway station

Alexey Fedoseev/SputnikI begin convincing them that I’ve bought up all the tickets to a particular compartment for my family, but my baby girl has fallen ill, the wife stayed with her, and I couldn’t really take my five-year-old son along all by myself, while changing my vacation days would be a problem at the office, so the tickets are going to waste! ‘Do you wish to upgrade your own seats, and travel with me instead at half – no, forget that – at a quarter of the cost – the money’s already been paid, after all!’”

“Of course, Feodosia to Leningrad is a 36-hour journey, and then some! Who wants to sit in a regular platzkart area with strangers scurrying about when they have a chance to switch to a comfortable private compartment, right? ‘He’s a decent working man, a parent, one of us’ – the parents might think… In spin tactics of this sort, a very helpful factor is always that the train is leaving in the next 10 minutes, and the decision must be made on the spot. As a result, here I am, traveling together with the family, headed south, in a private compartment.”

“I already have a pre-existing arrangement with the train conductors, I manage to get my hands on some cognac and snacks as a result, and here we are with the father of the family – smoking and being all chatty in the train car’s vestibule; I’m the soul of the party now, the happy, jolly one… We’re sharing stories about Leningrad, who lives where, talking about how stupid the planning is in those apartments… (And you could talk to me about any sort of planning – I know all of these typical state-sanctioned apartments like the back of my own hand, I mean – you have to, with my chosen profession! Of course, my ‘passengers’ are none the wiser).”

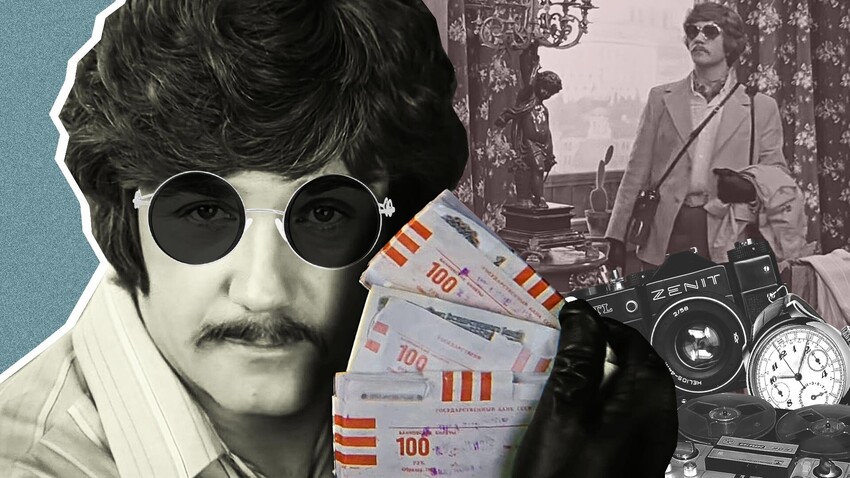

Leonid Kuravlev playing a burglar in a Soviet film.

Leonid Gaidai/Mosfilm, 1973“So, I tell him over another shot of cognac: ‘Got a nice Polish-made sideboard recently – you know, the one with that nice drawer for keeping your savings in?’

“And the wife would respond with: ‘Oh, bless you, who keeps their savings in sideboards anymore, so many burglaries these days! We usually keep ours by the washing machine, underneath the dirty laundry…’”

“By the time the train arrives in Sochi, I’ve got their address (from the registration stamp in their passports), their apartment key molds that I made while the entire family was sound asleep – I’ll have tortured both the parents and the kids with my stories until four in the morning. And while the family is on vacation, I’ll simply take the next train back to Leningrad, and quietly clean out their apartment. A couple of these ‘tours’, and you can live in comfort until next summer.”

Easy pickings: Soviet apartments were full of cash

A woman with a tape recorder. Such thing could have easily become a burglar's loot.

Scherbakov/SputnikThere were no banks in the Soviet Union because luxury had no place in a socialist state, (or so it was thought). Savings banks were the preferred means of storing your money. However, the Soviet masses weren’t financially savvy, and were often weary of having their money in an account.

Those who knew a thing or two often hated to spend time in line simply to withdraw their cash. Keeping it at home was the preferred way, along with ‘investing’ in expensive goods that could then be sold on the black market – things like jewelry, acoustic systems, TVs, wristwatches, fur coats and down jackets. Burglars loved to get their hands on those things.

There were various specializations among burglars. Fortochniki would enter apartments through windows, sometimes rappelling down from roofs. Medvezhatniki picked door locks and safes - sometimes with lock picks, while at other times with more serious tools. There were legends of a steel door, taken out of its frame using a cargo truck jack, using the load-bearing wall for leverage.

Proper recon was key

A posh Stalin-era house on Tverskaya street, Moscow

Ivan Shagin/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruHowever, any major burglary always began with proper surveillance. A former burglar confessed the following in an interview to the Ukrainian newspaper Segodnya: “First, we survey a random house from the outside, picking out apartments that, even from afar, have a more expensive look – the drapes and the glassed balcony.

Seeing if the owners can afford something like that, they must have money hidden away somewhere. We look not just at one – but two, three, four different options, and then execute the entry. First, we look at the locks. I’ll let you in on a professional secret: the more locks – the weaker the door! Meaning, if you see five or 10 locks, you know it’s gonna be a piece of cake, it’s easier to simply take it off the hinges. But it’s not ideal for house burglars: too much noise, and we like to work quickly and silently.”

If the apartment is under surveillance for a longer period of time, the burglars could figure out the make of the owners’ car, or how expensive the clothes they wear are. Once their financial status was clear, the breaking and entering could begin. “Say, we see that the lock is no big deal, so we begin ringing the doorbell. If someone’s home, they usually open or ask who it is. So we ask for a Vasya, Petya, or Raya, or about renting the place – whatever. No? Fine – ‘Sorry, our mistake.’ Usually, of the three or four apartments, one is suitable for the job: the locks won’t be a problem, the owners aren’t home, and so on”, the domushnik said.

The situation with home burglaries in the USSR was serious. In 1960, a total of 210,374 cases were registered – their number having doubled since 1956! That’s some 100 burglaries for 100,000 people. According to the 1960 Criminal Code, home burglaries were punishable by up to three years in prison.

However, the crime was usually carried out by a group, which brought the sentence up to six years – the same sentence one received for repeat offenses, as well as using tools for breaking and entering (keys, lock picks etc.). Repeat offenses could cost burglars up to 15 years behind bars. Nevertheless, in 1961, the annual figure grew to 224,000

A five-minute ransacking

A set of professional lock picks.

GeoTrinity (CC BY-SA 3.0)The method described below is referred to as the “five-minute”, where an apartment is usually picked at random, with little to nothing known in advance, aside from whatever was gleaned from the initial scoping. “In actuality, we’re there longer than five minutes, but no longer than 15-20 minutes. It gets riskier the more you’re there – the owner could return, then the burglary turns into armed robbery, and that’s a whole different crime and sentence.”

Professional burglars find it easier to research their targets ahead of time to avoid any unforeseen circumstances. This is usually done with tip-offs. In order to understand the owners’ habits, the surveilling parties would usually watch the windows for the lights turning on and off during the evening, as well as the time when the mailbox was checked.

Another way is watching the target’s electricity meter – the majority of Soviet apartments used to have them installed outside, in the hall, making them easy to read. Then there are the more exotic methods – such as putting some cigarette ash underneath the mat outside the front door.

It’s easier to feel safe when you know your target’s schedule. “If you’re going on a mission on a tip-off, and definitely know the owner won’t be back, then you can stay for 30 minutes, sometimes an hour. That’s enough to turn the apartment upside down, tear the baseboards off, butcher the pillows, check the winter boots and so on. In this case, you start with what you’ve been tipped off about, then begin your own revision of the home.”

The best place in an apartment to hide things?

Vases and flower pots also get checked, as do kitchen drawers and cupboards, followed by books, bedsheets, and mason jars in the kitchen – basically, everything that can be accessed without too much trouble. The thing the burglars really don’t like, however, is sorting through a messy heap.

“The balcony is a good place to hide something from a burglar. If it’s a five-minute burglary, and the balcony is full to the brim with stuff, there’s no time to sort through it all. And then, it’s just dangerous to do it – the neighbors could notice”, the domushnik says.

For the longest time, Soviet criminal statistics weren’t even a matter of public knowledge – the first data on crime began to be declassified as recently as the late 1980s – early 1990s, when the USSR was in its twilight, and crime was at an all time high, especially burglaries.

Today in Russia, with a fully functional banking system in place, money is no longer invested in fur coats and other valuables, and burglaries aren’t all that commonplace as they were in the Soviet Union.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox