How did Russian pickpockets operate?

As far back as pre-revolutionary Russia, in the courtyards of shabby urban districts one could witness the following idyllic scene: An elderly gray-bearded man is playing a particular game with street kids. He would hang a coat from a tree branch, attaching numerous little bells to it – smaller and larger ones. He would then button the coat up and place a banknote in the inner pocket. The boy who managed to extract it without setting off a single bell was the lucky winner.

“Why would I choose murder? I’m a natural born pickpocket!”

A pickpocket arrested at a tram stop, still from "The Meeting Place Cannot Be Changed," 1979.

Stanislav Govorukhin, 1979, Gosteleradio USSR, Odessa Film StudioPickpocketing is a criminal enterprise that few can master. The skill often manifests itself before the child hits puberty, which is why seasoned old thieves would often replenish their ranks by making future pickpockets out of small boys – reeling them in with the aforementioned game or impressive magic tricks. Criminologist Leonid Belogritz-Kotlyarevsky remembers the following story: “The professors of the thieving world would show right there, in a public square, how sleight of hand works: they’d pull out a snuffbox from the pocket of a passerby, sniff the tobacco and put it back without the the man ever noticing, simply continuing on his journey.”

Criminal researcher Aleksandr Kuchinsky writes: “Top-tier pickpockets are born. One must naturally possess a particular nervous system, instant, precise reactions, a particular constitution of fingers, palms, elbows and shoulders, as well as a necessary flair for the artistic.” And these are inclinations that required years of honing and were no less difficult than the training of magicians or cardsharps. By the way, if you ever hear someone mention “bending fingers” in relation to Russians, it’s a nod to the arduous practice of training finger plasticity while cooped up in prison, something the thieves would do with all that time on their hands.

“The skill is impossible to teach,” according to Soviet-era pickpocket Zaur Zugumov. “Nevertheless, thieves would exchange experiences behind bars. While serving our sentences in labor camps, in the workshop zones, we’d make a dummy and hang bells on it – that’s how they honed their thieving skills. With each ‘training session’, I’d try to get closer to the moment when not a single bell would ring.”

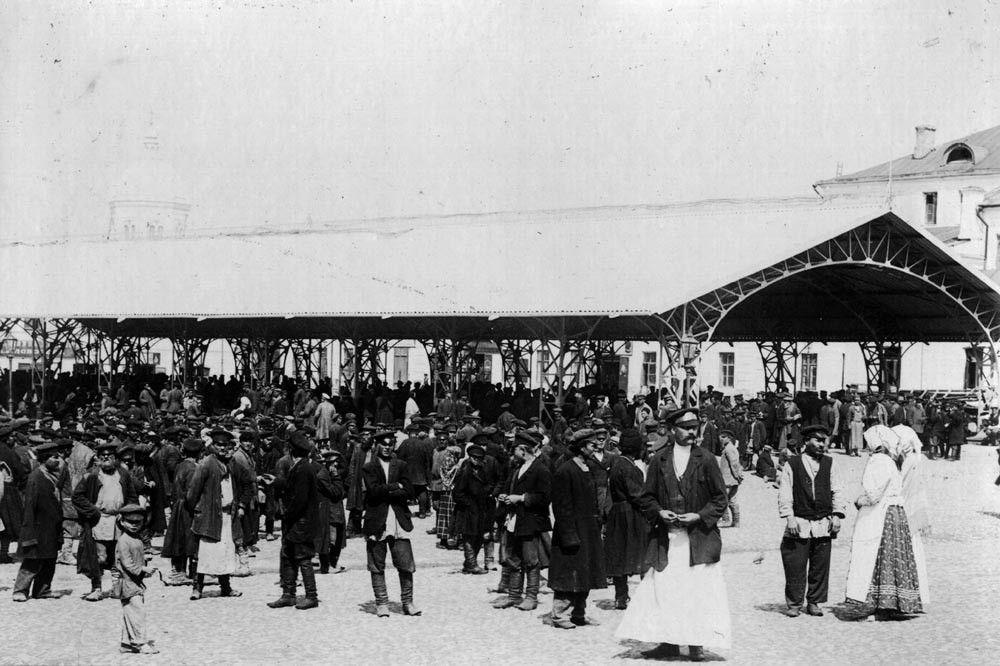

Labor exchange at Khitrov market, Moscow

Public DomainBut why the need for artistry then? Well, the first pickpockets appeared in Russia at the time the first paper money and exquisite body jewelry did – in the 19th century, in other words. They primarily worked the spots with the largest crowds – theaters, banks, expensive stores. In order not to arouse immediate suspicion with their manners and looks, the pickpockets had to look the part. “If any reader were to encounter such a thief, they’d have a hard time believing they were looking at a professional criminal,” prominent early 20th century lawyer and criminologist Grigory Breitman wrote. “This kind of thief is likely to resemble a doctor, lawyer, or an insurance agent: he has a pleasant appearance and impeccable manners; he wears a lavish suit, always custom-made by the best tailors. Understandably, such a thief – especially if he’s got front row seats at the theater, would not arouse anyone’s suspicion.

This is why the first pickpockets earned the right to be called the “gentlemen” of the criminal world. They never resorted to violence, threats and weapons, while their victims were primarily rich people, which cleared their conscience and ensured a more or less tolerant attitude from the tsar’s police. And it’s understandable that a thief who stole a wallet from some rich merchant is going to be treated better on the inside than a murderer or armed robber. “Why would I choose murder? I’m a natural thief, a natural born pickpocket! You can criss-cross Russia on foot and ask anyone: ‘Could a pickpocket murder another human being?’ You’d have everyone laughing in your face!” These words – as cited by pre-revolutionary journalist Vlas Doroshevich – belong to a pickpocket from Odessa, illegally detained on suspicion of murder.

In the 19th century, the “aristocrats” and the cops were often acquaintances – the cities weren’t so large at the time, with not too many thieves, either. Moreover, pickpockets usually worked in popular spots and areas. “You’re not likely to witness the same moral degradation among these thieves as you would with other criminals,” Breitman writes. “Nearly each one of them has a family, a place to live, children – and many grow up to be respectable people.”

There were police records on all the prominent thieves of the time; besides, they were well known to all the “filyors” (trackers) – cops in civilian clothing, working the public transport and places of mass gathering. But then, why weren’t the pickpockets actively hunted down?

Screeners, snatchers, anglers...

Yaroslavsky railway station, Moscow. Pickpockets could get lost quickly in a crowd like this.

Anatoliy Morozov/SputnikBeing educated men, versed in the word of the law, the thieves understood that they could only be caught at the scene of the crime, the moment they snatched a wallet from their victim’s pocket. If a filler or another cop misses the moment, they’d never be able to prove that the money didn’t simply fall out of the pocket. Finding the wallet on his person was next to impossible just seconds later: he’d either quickly pocket the money and dispose of it, or pass it along to an associate in the crowd, who’d casually walk away. The thief might even diligently help the victim look for their money. And if he’s suspected after all, the pickpocket’s artistic chops come into play, as he begins to profusely feign indignation. Following a search, no money would be found, of course. This is why the police in tsarist Russia would often end up detaining pickpockets as a preventive measure. The only thing they could really do is to exile the man from town, but there was little use in that, seeing as his preoccupation easily allowed him to “tour” all over the place.

Some were certainly caught red-handed. Breitman describes how a detective once apprehended the infamous female pickpocket – Anyutka-Vedma (“Anyuta the Witch”). One of St. Petersburg’s theaters once became the scene of four robberies in a single evening. The detectives were in a state of total confusion as they searched for a male pickpocket. At one point, one of them noticed an elderly woman in a suspicious hurry to make her way through the crowd.

“He saw that the lady put her hand in the pocket of a gentleman nearby. The delighted detective instantly grabbed the thief’s hand and held it in the man’s pocket without letting go. The gentleman then attacked the detective, proclaiming loudly: ‘Your hand is in my pocket!’. ‘My apologies, Sir,’ the detective replied. ‘Please, inspect my hands’. Taking a closer look, the gentleman saw that the detective’s hand... was gripping that of a well-dressed lady, who was trying in vain to free her wrist. ‘Oh! Madame!’ was the only phrase the astonished gentleman could muster.”

City police officers in St. Petersburg. April 2, 1917.

SputnikAfter the February revolution of 1917, the Provisional Government gave amnesty to the prisoners of the tsarist regime: numerous thieves of all ilks were set free. Moreover, the conditions had changed: there was now public transport; the railway network was expanded; places of mass gatherings grew in number. The people, meanwhile, grew poorer. Change didn’t spare the pickpockets either. While they never lost their aristocratic status in the criminal world (continuing to refuse to inflict bodily harm on their victims), what changed were their methods.

Schipachi and Verkhushniki (“snatchers” and “toppers”) aroused a certain measure of disdain from the rest of the pickpocketing world – they picked coat pockets. “They go to work as a whole group,” Kuchinsky writes. “And they prefer mass gatherings – demonstrations, public celebrations, busy markets. While some schipachi were tasked with misdirecting the victim, others got to work on the pockets and handbags. Then the teams switch places. If the operation is nixed, the pickpockets could push back the outraged victim, distract them and even organize a comic spectacle with screams of ‘Catch the thief!’”

Shirmachi (let’s call them “coverers” or “screeners”, for lack of a better word, since shirma in Russian is the screen you use to change clothes) were the type that would cover the handbag or the pocket of the victim with a “cover” – perhaps a folded coat or a bouquet of flowers, and use the same hand holding the cover to extract money, using the free hand to pass the ticket aboard public transport, wave around a newspaper or gesticulate in order to distract the victim’s attention. Here, just as in the olden days, one, again, had to rely on their flair for the artistic. Zugumov recalls how he stole a wad of cash from a worker who’d just received his pay. The money was in the pants pocket under another layer of trousers: “As soon as the tram approached, I entered together with the victim. Having made sure that the money was indeed there, I got to work. There was a moment when he spoke to me. Imagine my predicament: the left hand was inside my victim’s pant zipper, with the tips of my fingers gripping the wad of 10-ruble bills by the corners, as I’m pleasantly smiling at the victim and continuing the dialogue…”

There were even the so-called rybolovy – or “anglers”, who used fishing hooks and line to extract the wallet from the bag. They often worked the long-distance trains, taking the top shelf and lowering the hook down into the belongings of the cabinmate below.

My hands are my bread

Policemen at a market in Moscow, 1909-1910

A. Melitonyan's collections/Russia in photoThe highest caste of pickpockets were the pisary – the “etchers”, who would cut open (or raspisyvali – “etched”) the clothes or bags of people in the crowd. “Up until around the 1970s,” Zugumov recalls, “they would sharpen a 20-kopek coin and, using the edge to work. One could easily hide it inside the mouth. So much so that they’d often forget it was even there, and eat and sleep with it in place.”

But why hide the coin in the mouth? Well, Soviet laws had in time evolved to be more effective in their capture of thieves – there was the new legal concept of “stealing with the use of technical means”. The sharpened coin is obviously a means – or a tool, and finding it could easily land the pickpocket in prison for up to 10 years. By the way, it was the “anglers” who came up with a solution for that, fully opening up their fishing rods right in front of the police and claiming it had nothing to do with stealing. That clever action could only ever be proven to be an ordinary theft, which meant a sentence of only up to five years.

The main tools of the thief were, however, his psyche and hands. That’s why his only mortal enemies were bad habits and ageing. “Lavish dinner parties and sleepless nights, spent in the company of women or playing a game of Preference, only dulled the person’s reaction and alertness,” Kuchinsky writes. “Smoking and eating too much affects the sensitivity of the fingers. And then, on top of all that, ageing would add ossification of movement.”

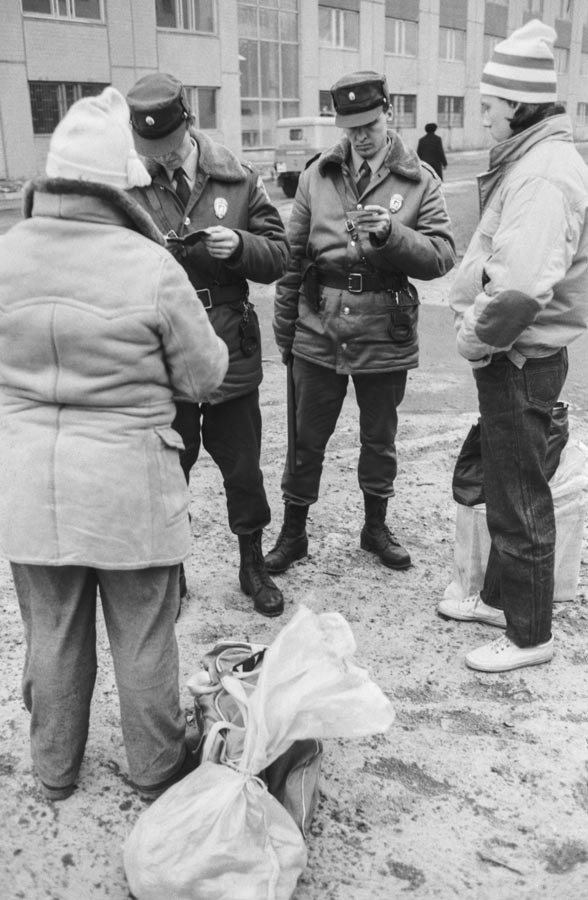

Soviet militia in 1991.

Anatoly Morkovkin, Alexander Shogin/TASSA prison sentence or a sting at a labor camp were the thief’s biggest fear, of course. They’ll ruin everything there – your psyche, your hands. The Soviet penitentiary system did not exhibit any of the shades of generosity one could expect from the pre-revolutionary police. In the 1920s, which saw the height of pickpocketing, the thieves could simply have their fingers broken. Being sent to do hard labor on the Dnepro Hydroelectric Power Plant or the Belamar Channel, coupled with horrible prison living conditions – all of that destroyed any hope for the plasticity of a man’s fingers. So the more professional pickpockets would do their utmost to escape manual labor on principle. The so-called “thieves’ concepts” were developed. The main one among them was a ban on all types of physical labor, resulting later in an all-out ban on work in general. In this way, pickpockets could afford to remain the elite of the thieving world even in the 20th century, becoming the de-facto leaders of the movement against collusion with the prison administration.

Zaur Zugumov

Zaur Zugumov's VK pageThe methods used by pickpockets have remained the same throughout the history of the profession. The only things that changed were the catch and the scenes (and with them – the means) of the crimes. Today, in the era of cashless payments, while physical card theft makes zero sense, the business of pickpocketing is obviously going through a rough patch: nobody walks around with impressive sums of cash on them anymore.

“There are only one or two pickpockets left around. ‘Toppers’ everywhere”, Zugumov sighs. “All they do is steal phones from kids – from jean pockets in the summer and outer coat pockets in the winter; then they sell them off for pennies to profiteers. Perhaps, it’s simply that the times have changed…”

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox