Who was Alexander Nevsky, the legendary Russian prince?

Surrounded by Russians led by Alexander Nevsky, the knights of the Livonian Order (an autonomous branch of the Teutonic Order), wearing heavy metal armor, break the ice of the lake with their weight and drown. That’s the traditional story of the Battle on the Ice of 1242 and that’s how it’s shown - for instance - in Sergey Eisenstein’s classic 1938 movie, Alexander Nevsky.

The movie was a piece of propaganda and this scene shaped the perception of Alexander Nevsky for years to come. It was 1938, war with Germany was close at hand. In Eisenstein’s movie, made under Politburo supervision, the main organ of the CPSU, the knights of the Teutonic order symbolized the Germans, and Alexander Nevsky’s stance was undeniably patriotic.

“Go and tell everyone in foreign lands that Russia is alive. Let them come to visit us without fear. But if someone comes to us with a sword, he will die by the sword. The Russian land stands and will stand on that!” – Nevsky says in the movie. But he never said anything like this in reality. There was yet no Russian state in the 1230s-1240s, when the Battle on the Ice happened. Alexander was actually fighting on the side of the Novgorod Republic.

The Battle on the Ice

The Battle on the Ice. A still from "Alexander Nevsky" by Sergey Eisenstein

Sergei Eisenstein, Dmitri Vasilyev/Mosfilm, 1938In the late 1230s, the Russian lands were ravaged by the Mongol-Tatar invasion. The Swedes and the knights of the Livonian and Teutonic Orders wanted to use this period of weakening to attack the Russian lands. In 1240, the knights of the Livonian Order besieged and took Izborsk and Pskov. But the people of the nearby Novgorod Republic, afraid that the Livonians might attack them as well, summoned a powerful prince to protect them – Alexander Yaroslavich (1221-1263), who was later known as Alexander Nevsky.

In 1240, Alexander and his warriors first encountered several Swedish military vessels at the mouth of the Neva river. Summoning forces from the citizens of Novgorod and Ladoga, Alexander defeated the Swedes in the so-called Battle of the Neva (July 1240). Later, beginning from the 15th century, Alexander became known in the chronicles as “Nevsky” because of that battle.

In 1241, Alexander came to the Novgorod region and with his band of warriors, forced the Livonian knights out of the region. In 1242, he took back Pskov, killing about 70 knights. In April 1242, Alexander, leading the armies of the communities of Novgorod and Vladimir, encountered the Livonian knights near Lake Peipus (in Russian, Chudskoye Lake) on the border between contemporary Russia and Estonia.

Lake Peipus (in Russian, Chudskoye Lake) where the Battle on the Ice happened

Laima Gūtmane (CC BY-SA 3.0)According to contemporary historians, there were some40 knights, supported by approximately 150 foot soldiers, on the Livonian side, and about 800 warriors on Alexander’s side.

The legend has it that Alexander and his warriors fought the knights on the surface of the frozen lake, the ice cracked, and dozens of knights drowned. However, the Livonian Rhymed Chronical states that “swords were ringing, helmets were being hacked, as fallen ones fell on the grass from both sides,” suggesting that the battle happened on solid ground. The Russian chronicle claims the Russians overpowered the Livonians and chased them for nearly 5 miles (7.5km) on the frozen lake, to the opposite shore. It was probably during the pursuit that some of the knights may have drowned, but there are no written records proving this.

Russian sources say the battle left 400 Livonian dead. However, the Livonian chronicle says 20 knights were killed and 6 were captured by the Russians. The sources are, however, rather sparse. We only know that Alexander won the battle, effectively keeping his promise to protect the Novgorod republic from the Teutonic and Livonian orders.

Collaboration with the Mongol-Tatars?

"Alexander Nevsky" by Pavel Korin

Tretyakov GalleryAfter the battle, the Livonian order was on its back foot. Alexander continued campaignin, against the Lithuanian princes. At the same time, in 1246, his father, Prince Yaroslav of Vladimir, was summoned by Batu Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, to Karakorum, the capital of the Mongol Empire at the time, and poisoned there.

Alexander and his brother Andrey, according to their father’s will, inherited the “Russian lands” – Andrey became the prince of Vladimir, and Alexander became the prince of Kiev and Novgorod. However, Kiev, the capital of the Kievan Rus’, was burned to the ground during the Mongol invasion and lost its significance. Alexander stayed in Novgorod.

Prince Alexander Nevsky. Miniature from the Tsarskiy titulyarnik (Tsar's Book of Titles).

Collective of Kremlin Armory artistsIn 1251, Prince Andrey fled Russia because of a serious conflict with the Mongol-Tatars, and Alexander became Grand Prince of Vladimir – in fact, the most powerful prince of the Russian lands at the time. As such, he had to communicate and collaborate with the Mongol-Tatars in order to protect his people from punitive campaigns. For example, in 1259 he forced the people of Novgorod to start paying tributes to the Mongol khans.

In 1263, Alexander was returning from a journey to the Golden Horde, where he had tried to persuade Berke Khan (Batu Khan’s brother and successor) not to draft Russians into his army. On the way back, Alexander fell ill and died. The most interesting part of his story, however, comes after his death.

Alexander Nevsky the legend: from Ivan the Terrible to Peter the Great

Alexander Nevsky on a throne. Miniature from the Tsarskiy titulyarnik (Tsar's Book of Titles).

Russian National LibraryThere was an important detail in Alexander’s will – he endowed his youngest son Daniil (1261-1303) with the Duchy of Muscovy. Daniil became the founder of the Moscow dynasty.

In 1547, Ivan the Terrible became the first Tsar of the Moscow Tsardom. The same year, Alexander Nevsky was made a saint by the Russian Orthodox Church. This was done at the behest of Macarius, Metropolitan of Moscow. By glorifying Alexander (as well as many other Russian princes and holy men of the past) as a saint in Moscow, Macarius was creating an ideological religious foundation for the new state.

It was also important that in the 1540s, Moscow continued its war with the Livonian confederation. Alexander Nevsky’s image as the first Russian prince who defeated the Livonian order, also contributed to such ideological targets.

Alexander’s feat was again brought up in the early 18th century, when Peter the Great defeated Sweden in the Great Northern War. In 1710, when the war was still in full swing, Peter ordered the Saint Alexander Nevsky Monastery (later, Alexander Nevsky Lavra) to be built in St. Petersburg. Peter built it where he believed the Battle of the Neva had taken place in 1240 (it actually took place 12 miles/19 km from the site of the Alexander Nevsky Lavra).

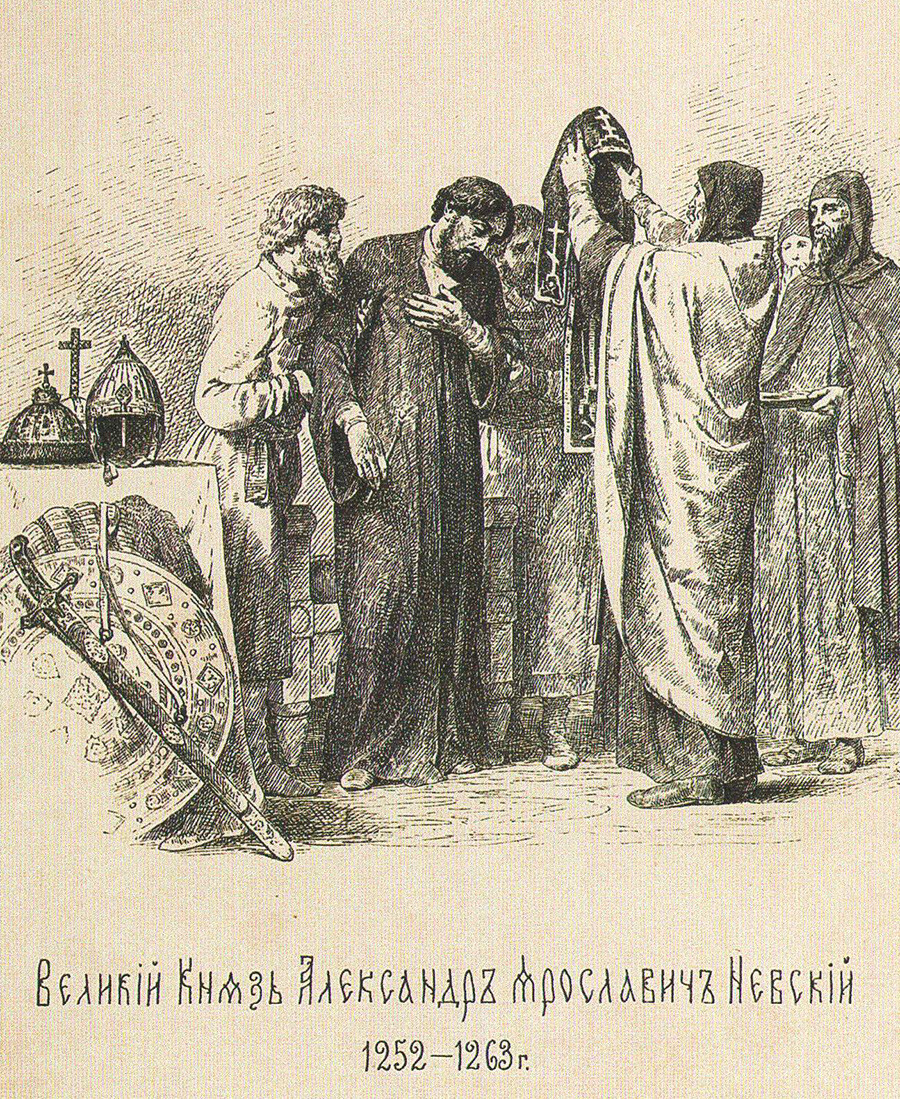

Alexander Nevsky taking a monastic oath shortly before his death. A drawing by Vasiliy Vereschagin, 1896.

Public domainTwo years after celebrating victory over the Swedes, in 1723, Peter ordered Alexander’s relics to be moved from Vladimir to Saint Petersburg, to be kept, as a symbol of Russia’s victory over Sweden, in the Alexander Nevsky Monastery.

Alexander became the patron saint of Saint Petersburg, and Peter deliberately made August 30 (Old Style) his feast day - the day the Treaty of Nystad was signed in 1721, concluding the Great Northern War. It is also important that Alexander himself became a monk on his deathbed, as many Russian princes traditionally did. However, after Peter the Great moved Nevsky's relics to Saint Petersburg, he ordered the Russian Orthodox Church to remember and glorify Alexander as a military leader, not as a monk. Since that time, Alexander Nevsky has been considered the heavenly patron of the Russian army.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox