These days, wind power is popular all over the world as an environmentally friendly way to generate electricity. The capacity of wind turbines increases each year and currently amounts to hundreds of gigawatts. In today's Russia, wind power is not very common and accounts for just 1 percent of the country's total electricity production (although in 2020 the capacity of the country's wind turbines tripled). A hundred years ago, however, Soviet scientists were extremely enthusiastic about the idea of using the wind to generate power.

Kalmykia. Sokol wind turbine, 1977.

E. Rogov/SputnikAfter the 1917 revolution, electrification was one of the Bolsheviks' top priorities. At the time, the country's few power plants ran on peat, coal and oil, and it was clear that for a dramatic increase in energy production a new source of energy was needed, and it would have to be cheap and abundant. This was why scientists turned their attention to water and wind energy.

Astrakhan. This wind power plant helped to irrigate agricultural areas, 1969.

Valery Shustov/SputnikIn the end, hydroelectric power turned out to be more efficient and accounted for a significant share of the energy supply of the USSR (and in Russia, 20 percent of electricity is now generated by hydroelectric power plants), at first great hopes were placed on wind power as well.

This is the settlement of Dixon, located beyond the Arctic Circle. April 1954.

Vladimir Savostyanov/TASSIn 1918, the Central Aerohydrodynamic Institute (TsAGI) was founded in Moscow. It developed the first wind turbines with a capacity of up to 30 kilowatts to enter serial production. In terms of modern technology, this amount of energy would be enough to power a refrigerator for a month.

Small generators like this had many practical applications. They were in demand in remote parts of the USSR in places like Buryatia and on stations along the Northern Sea Route. They were used to charge batteries, feed radio nodes or light houses. In total, several thousand small wind turbines were produced.

Soviet wind generator on Franz Josef Land archipelago in the Arctic Ocean.

Ilya Timin/SputnikOther design bureaus developed wind turbines too. For example, in 1931 the most powerful wind turbine at that time was built near Balaklava (Crimea). It had a capacity of 100 kilowatts.

The wind turbine in Balaklava.

Public DomainModern industrial wind turbines reach a capacity of 6-8 megawatts, but a century ago, 100 kilowatts was considered a real breakthrough.

The Balaklava wind turbine weighed 9 tons and had a blade span of 30 meters. It was invented by Yuri Kondratyuk, one of the pioneers of astronautics (he also calculated the flight path to the Moon), who was also involved in the design of wind farms.

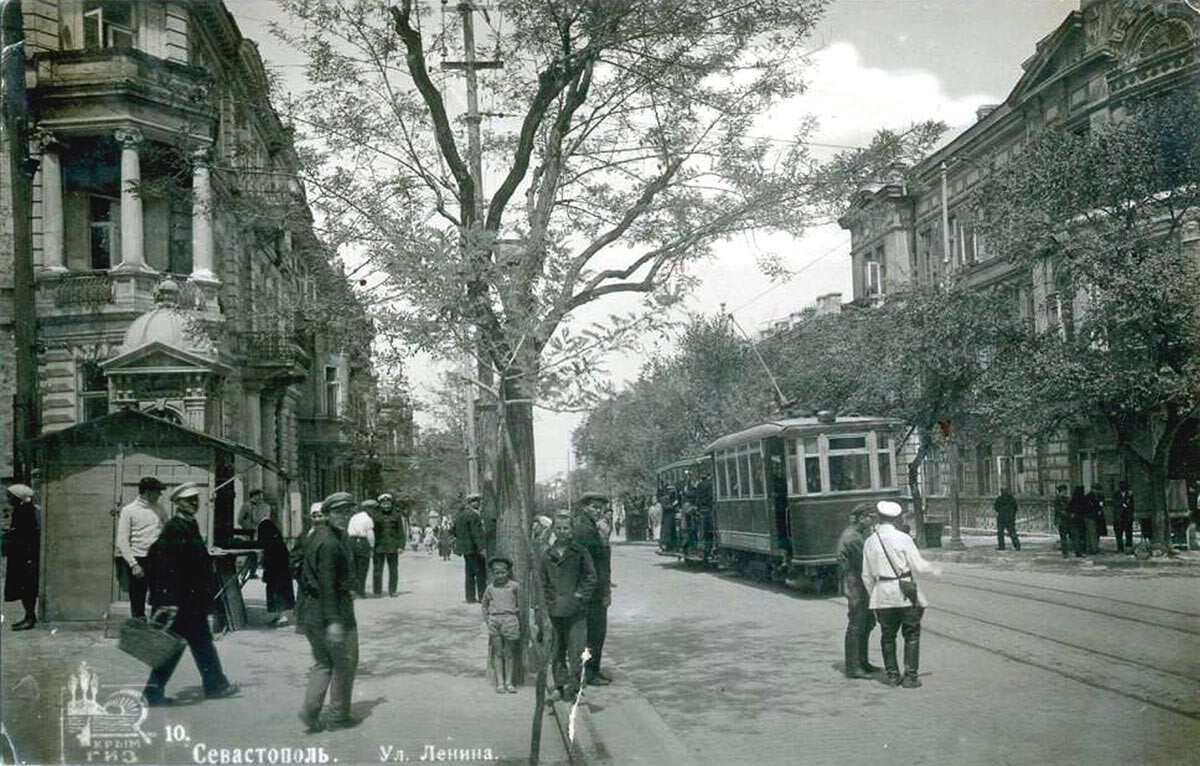

The tram in Sevastopol, 1930s.

Public DomainThe Crimean wind turbine powered up the entire Balaklava-Sevastopol tram line.

However, during World War II, both the generator and the tram line were destroyed beyond the point of repair by shelling. In the mid-1930s, there was a plan to build another wind farm in Crimea, near the top of the Ai-Petri mountain, but the project was never implemented.

Ufimtsev's wind station in Kursk.

Stanislav KretovThe main problem of the first windmills was the lack of storage technology, which meant that when there was no wind you could be left without electricity. A solution to the problem was found by Anatoly Ufimtsev, a self-taught inventor from Kursk (in southern Russia). A wind farm with a storage mechanism that he built in 1931 can still be seen in his old house. The money for the project came from TsAGI and the prominent Soviet writer Maxim Gorky. Ufimtsev's windmill illuminated his workshop, his house, and part of the street on which he lived. The wind farm continued to operate after the inventor's death in 1936. Until 1957, its operation was maintained by a local mechanic, who had taken part in its construction. However, the windmill had to be stopped as some of its parts were no longer fit for use and restarting it again proved impossible. These days, Ufimtsev's house has become one of Kursk's tourist attractions and holds particular appeal for technology enthusiasts.

Wind power stations in the Far Eastern city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur, 1972. This is the new hotel called Voskhod ("Sunrise").

G. Khrenov/TASSWith the development of the energy sector, the shortcomings of windmills in comparison with hydropower, nuclear or gas energy became obvious. Nevertheless, wind power continued to be used when necessary, including for industry and the “great construction projects” in the Far North and the Far East.

Wind power plant on the Absheron Peninsula, Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, 1987.

V.Kalinin/SputnikIn 1973, a state program for the development of wind energy was adopted.

One of the first full-fledged wind farms in the USSR was built in the late 1980s on the island of Saarema (Estonia), which consisted of 64 wind turbines and provided energy for a fish factory.

Windmills on the island of Saaremaa, Estonia, 1989.

At about the same time, the Raduga-1 generator with a capacity of 1 megawatt was developed. One of these generators has been preserved in Kalmykia (in southern Russia). It was operational until 2014, but has now been abandoned.

For household use, the Vetroen enterprise produced small windmills called Romashka (“daisy” in Russian). Some of these devices, mainly wind pumps, can still be found at dachas across the country.

“It works around the clock and for free,” writes one user of such a pump. “It pumps up water from a well from a depth of up to 8 meters.” Among the other advantages of the device, the user notes its safety since there are no parts that can burn out.

Romashka wind station at the exhibition in Moscow, 1986.

Lembit Mikhelson, Vitaly Sozinov/TASSIn 1989, the USSR adopted a comprehensive program for the use of alternative energy but this was never implemented due to the country’s collapse.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox