Ivan, the first Russian tsar, began to be mentioned as “the Terrible” in the 16th century. This word in the Russian language at the time was close in meaning to the words ‘powerful’ and ‘great’ and, for contemporaries, it was obvious why the tsar received such a nickname – it was during his reign that the Kazan and Astrakhan Khanates, the remnants of the collapsed Golden Horde, were subdued.

The tsar wished the whole civilized world to know about it, but how could this be done in the absence of international press? Its role at the time was performed by the dispatches and notes of foreign ambassadors. And how to impress them? Certainly, with sumptuous feasts! It was at them that the oriental rituals and customs, which were adopted by the Russians, were especially vivid.

"Russian Embassy to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II in Regensburg," 1576

Shakko (CC BY-SA 4.0)Here is what an anonymous English merchant who visited Ivan the Terrible’s feast in 1557 wrote: “When dinner time came, we were ushered into the tsar’s dining chamber. <...> At the highest end of one [table] sat His Majesty, his brother and the captive tsar of Kazan. Below, sat the son of the tsar of Kazan, a child about five years old. At the third table sat the so-called Circassians, who served the tsar in his wars against enemies.”

It was important for Ivan the Terrible to show foreigners: indeed, the Khanate of Kazan has been conquered and its last Khan serves the Russian tsar. The Khan the Englishman described was Yadigar-Mohammed Khan, who, after the capture of Kazan in 1552, entered the service of Ivan the Terrible and then was baptized into Orthodoxy with the name of Simeon Kasayevich. At the tsar’s feast he was accorded the highest honor – as a Khan, he was considered equal to the tsar and sat at his table.

The Englishman also mentions Circassians at Ivan the Terrible’s feast – ancestors of Adygs and Kabardins, people who owned the coast of the Caspian Sea in the middle of the 16th century and acknowledged the Russian tsar’s authority over them. By this time, communication between Russian nobles and the nobility of the former Horde became very close, there were many marriages, which strengthened the connection between Russia and the territories of the former Golden Horde. Tsar Ivan the Terrible himself was also related to the Circassians.

Simeon Bekbulatovich by unknown painter, second half of the 16th century. Simeon Bekbulatovich, the nephew of the tsar's second wife, was accordingly the tsar's nephew.

Public domainEstablishing family ties with the nobility of the conquered lands is an Eastern tradition, which was brought to Russia by the Horde khans. Back in the 14th century, the ruler of the Golden Horde, Uzbek Khan, married his sister, Konchaka (baptized into Orthodoxy as Agafia), to Moscow prince Yuri Danilovich. Ivan the Terrible’s father, Moscow Prince Vasily III, married Solomonia Saburova (the Saburov family descended from the Tatar nobility who had moved to serve Moscow). At the same time, Vasily III arranged the marriage of his sister Evdokia and the Tatar prince Kudai-Kul, the son of the Khan of Kazan.

The second wife of Vasily III was Elena Glinskaya – from a family that traced its lineage back to Mansur, the son of the Horde’s temnik (military commander) Mamay, the one that was defeated in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380. It was Elena Glinskaya who became the mother of Ivan the Terrible.

Furthermore, Tsar Ivan’s second wife was Maria Temryukovna (born Kucheney), a Circassian princess. Her nephew was Sain-Bulat, baptized into Orthodoxy as Simeon Bekbulatovich. He even ruled Moscow for 11 months in 1575, while Ivan the Terrible was in self-imposed exile.

The crowns of the Moscow Tsardom in the Kremlin Armoury

Shakko/WikipediaThe Monomakh’s Cap, the main crown of Moscow princes since the end of the 15th century, symbolized the origin of the power of Moscow rulers from the princes of Kiev. But, during ambassadorial receptions at the Moscow court, crowns of other lands – Astrakhan, Kazan, Siberian khanates – were placed on stands and tables next to the throne, in order to emphasize the power of the Russian king over these khanates. These crowns also necessarily participated in the ceremonies of the crowning of the Russian tsars.

"Ivan the Terrible. An English embassy" by Evgeny Danilevsky. Note that the foreign envoys are pictured without their weapons.

Studio of military artists named after M.B. GrekovTaken from the diplomatic tradition of the Golden Horde, the Russians adopted the rule that no one should enter the royal court with weapons. Such were the rules in Sarai, the capital of the Horde princes. And European diplomats, whose honor demanded that they always carry weapons, had to surrender their swords when entering the Kremlin.

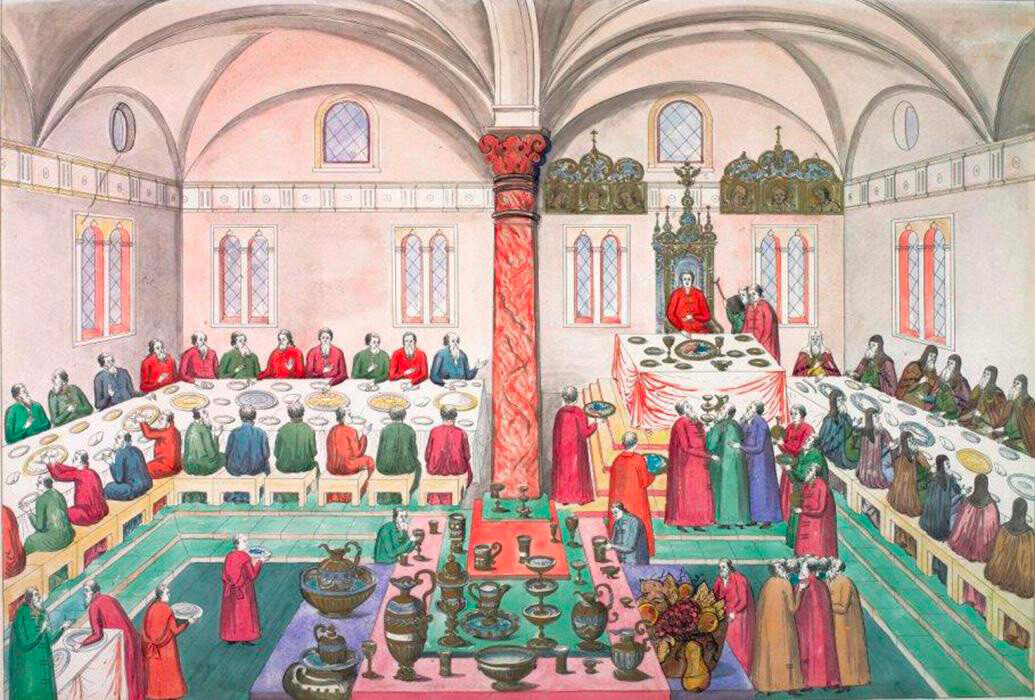

The feast in the Palace of Facets, a 16th-century drawing

Moscow Kremlin MuseumsIn Mongol palaces, a bowl of kumis (fermented dairy product) was brought before a diplomatic reception – the khan himself drank from it and then everyone else, including the ambassador who arrived. At Russian receptions, drinking wine “from the hands of the tsar”, that is, from a goblet or bowl sent on his behalf, on the contrary, ended the reception. Especially respected ambassadors were then invited to the tsar’s feast.

Early 20th century Russian postcard of Ivan the Terrible.

Michael Nicholson/Corbis/Getty ImagesBeginning with Ivan the Terrible, Russian rulers wore a tafya, a round cloth cap that tightly covered the back of the head. Tsar Ivan, as was the custom of the military leaders of the time, including those of the Horde, shaved his head – during long campaigns, hair could become a breeding ground for contagious diseases. It was considered uncivilized to walk around with a bald head, so the tsar and the boyars wore a tafya. They could wear other headwear over it if necessary or they could only wear it. Home tafyas were simple, while ceremonial ones were decorated with gold embroidery and precious stones.

Some Horde’s features remained in the ceremonial attire of Russian tsars. Their ceremonial guards held saadaks (a Turkish name for ‘bows’) and were dressed in ceremonial clothes, which were called terlik (a word of Mongolian ‘origin’). By incorporating Eastern traits and objects into their ceremonial, the Russian tsars showed their new subjects, the population of the former khanates, that their new tsar possessed the familiar Eastern signs and attributes of power.

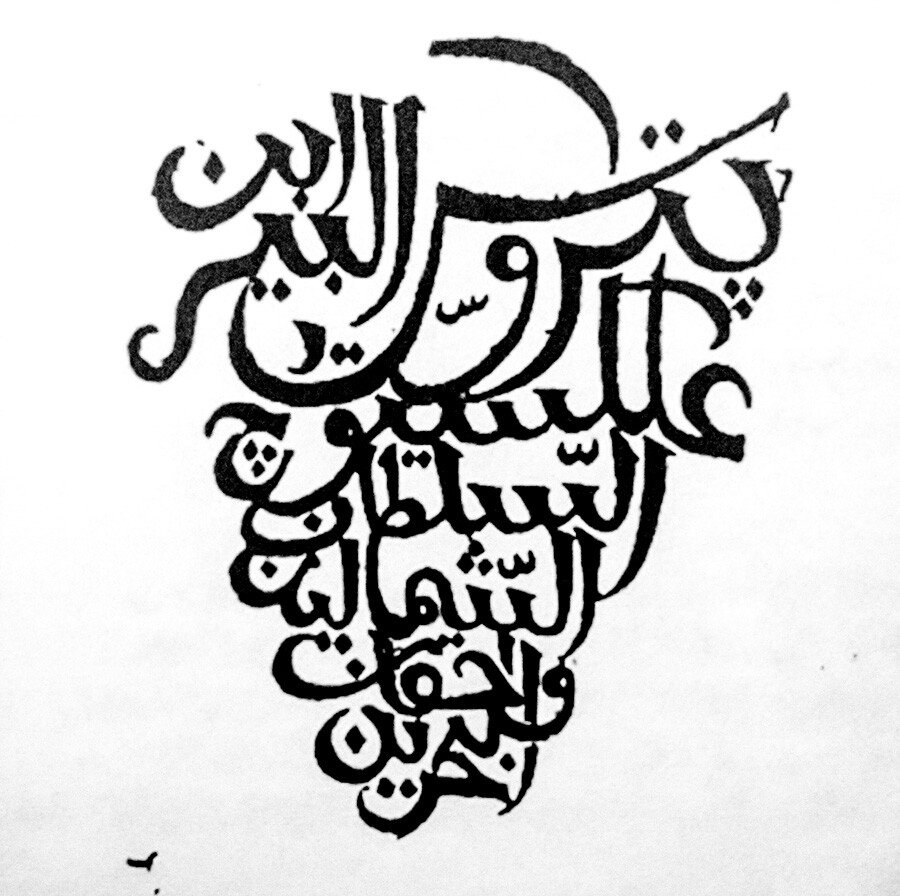

The tugra of Peter the Great

State Museum of Oriental ArtRussian tsars had a special signature for correspondence with the Muslim world – the khans of the remnants of the Horde and the sultans of the Ottoman Empire. It was called ‘tugra’ and it was a special sign of the ruler, put on all his outgoing documents. In their diplomatic correspondence with the East, Russian tsars wanted to use the symbols of power that would be familiar to the Muslim world.

The first known tugra of the Russian tsars dates back to 1620 and the last person to use it in correspondence was Peter the Great. “Peter the First, son of Alexei, Padishah of Russians” – this is how the tugra of the Russian Emperor was translated from the Old Ottoman.

It was under Peter the Great that the relationship of dependence of the Russian state on the khans was completed. The last person to whom the “pominki” (a symbolic tribute) was paid was the Crimean khan. As for court ceremonies and royal dress, it was Peter who decided to finally abandon the old Moscow traditions, dressed his subjects in European clothes, and introduced new court rules – for example, the crowns of the Russian Empire began to be used in ceremonies instead of the khans’ crowns.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox