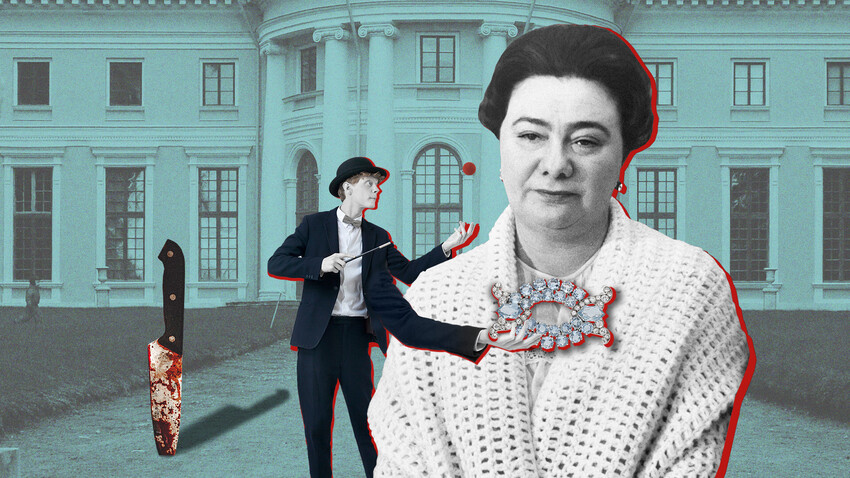

One night in July 1981, privileged children of high-ranked Soviet officials gathered in the Arkhangelskoye Palace near Moscow. The whole historical estate was reserved for a private party that would turn into a night of theft and, eventually, a murder.

On the night of July 28, 1981, private cars flocked to the Arkhangelskoye Palace near Moscow. Children of high-ranking Soviet officials gathered for a night party of drinking champagne, dancing to prohibited Western music and showing off the obnoxious wealth provided by those very people who proclaimed to have built the egalitarian Soviet society.

Arkhangelskoye Palace.

Yarin/SputnikThe daughter of the then Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev named Galina Brezhneva often frequented such parties. And that night was no exception. She arrived in style, dressed up and wearing diamonds.

Galina Brezhneva.

Archive photoHowever, a series of unfortunate incidents marred the nocturnal fun. At first, one of the guests complained to the administration of the estate that he had lost an exclusive cigarette case. Then, a few others realized they had some items missing. Finally, to everybody’s awe, Brezhnev’s daughter announced she was missing a diamond brooch she had reportedly borrowed for the occasion from the Diamond Fund of the Kremlin Armoury.

Different diamond and emeralds brooches in the Diamond Fund of the USSR.

SputnikTrembling staff were frantically searching each and every room in the estate hoping to find the jewelry when they made yet another shocking discovery. One of the windows was left ajar, a blood trail ran from it into the woods. Following the trail, the staff stumbled on the body of a man who had been stabbed.

Soon enough, the Moscow police force was rushing towards the crime scene. Considering that Brezhnev’s daughter was directly involved, the case was of paramount importance to the chief ranks of the Soviet police who could have lost their offices over this. The case required the best investigator.

“It was a real emergency. I personally don’t remember anything like that,” said lead investigator Arkady Chernov in an interview that he gave years later, after the fall of the USSR.

The police quickly identified the deceased. The man’s name was Nikolai Rizunov, an ex-pickpocket who had paved his way up in the criminal underworld to become a well-known thief-in-law.

Realizing the murder of the thief-in-law mixed with theft from Brezhnev’s daughter could quickly spiral out of control, the flabbergasted investigators rushed to question party guests. Soon, they had their suspect.

One by one, the guests remembered there was a young man who bumped into them while dancing. Not knowing his real name, the investigators dubbed the suspect the “pickpocket”. They knew the pickpocket came with one of the guests named Inga Solovey, an 18-year-old daughter of another high-profile Soviet official.

The investigators questioned Inga Solovey, but failed to obtain the suspect’s true identity from her.

“It was clear that the girl did not give a truthful testimony and was trying to steer her acquaintance away from responsibility,” said lead investigator Chernov.

Soon after Solovey was put in custody, the investigators learned that the girl was pregnant.

Feeling pressure to solve the case fast, but facing resistance from the uncooperative suspect, the investigators devised a better plan than to keep pressuring the stubborn and pregnant girl into confession. They would let her go, but they would also establish around-the-clock covert surveillance of the girl.

“I didn’t suspect a thing. I thought it was my father who got me out of it. I started calling my friends, my girlfriends,” said Solovey in an interview she gave years later.

However, to the investigators’ discontent, the girl was only visited by one female friend. There was no sign of the wanted “pickpocket”.

One day, the investigators obtained information from their informants about a magician who performed magical tricks in a restaurant in one of the lavish hotels in Moscow. Apparently, the magician could place various objects like card decks and cigarette packs inside an empty glass bottle. The police knew it was their suspect when the restaurant’s staff confirmed that he looked like the man on the police sketch.

Pickpocket thief Andrei Kurdyaev.

Archive photoThe police probed graduates of various circus schools throughout the USSR. Looking through the files, they found their suspect: a 19-year-old man named Andrei Kurdyaev.

Kurdyaev was born in Kiev in the family of a circus performer named Leonid Kurdyaev. Kurdyaev senior taught his son the art of performance, but failed to make him an artist, since he was incapacitated after an accident that happened during one of his performances. Left with no supervision, the son chose a criminal path.

Andrei Kurdyaev honed the art of pickpocketing to the finest. However, after the arrest of his criminal mentor in Kiev, the man left for Moscow fearing arrest. In the Soviet capital, he made money by pickpocketing and performing magic tricks for the public.

One day, Kurdyaev was relaxing on one of the Moscow beaches. This is when the dishonest magician met the daughter of a high-profile Soviet official. For Kurdyaev, the infatuated girl was his way to the top of Soviet society; for Solovey, he was a talented circus performer forced to hide from powerful enemies. The couple fell in love.

Matching the earlier photos of Andrei Kurdyaev to the photos made by the surveillance team working with Solovey, the investigators realized the suspect had been under their noses the whole time. Only he was dressed as a woman.

The police moved to arrest Kurdyaev, who had been visiting his paramour Inga Solovey this whole time. Kurdyaev resisted the arrest and tried to stab a policeman, but failed. He was apprehended and delivered to a station for questioning.

However, the investigators failed to obtain much information from Kurdyaev, who kept quiet and did not volunteer much information. Investigators had an impression the man feared something or someone, which led them to believe there might have been other organizers of the heist. But, there was no direct evidence to confirm their suspicions.

Besides, they had the man’s confession, albeit too terse.

“I’ll never forgive myself for everything that happened. I have no one to blame but myself. I was a victim of my own stupidity and arrogance. But, it is not Inga’s fault,” said the suspect.

Kurdyaev also confessed to stabbing the thief-in-law Nikolai Rizunov, who confronted him in private during the party. Nonetheless, the man refused to confess to the theft of the diamond brooch from Brezhnev’s daughter.

Formally, the crime was solved. But, the nagging feeling of reticence troubled lead investigator Arkady Chernov, who wondered why the suspect was so frightened and uncooperative, even after he had confessed to all the crimes he was charged with but one.

Chernov would never have answers to these questions. Two weeks into his arrest, Kurdyaev was found hanged in his cell. The official version was that he committed suicide. However, to this day, many doubt that Kurdyaev killed himself.

Learning about the death of the man she loved, Inga Solovey had a mental breakdown and a miscarriage.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox