Peter the Great’s daughter demonstrated an easy temper and almost frivolous behavior. She loved fun, luxury, expensive and revealing attires. She was often seen in the company of different young men. Peter the Great didn’t have time to marry his daughter off (for example, he received a refusal from future French King Louis XV).

Portrait of Elizaveta Petrovna by Vigilius Eriksen

Tsarkoye Selo Museum-ReserveShe had almost no chance of ascending to the throne – she was next after her nephew Peter II, her older sister Anna and their descendants. But, in the end, for tsarevnas like herself, marriage was, first of all, a political act. From a very young age, Elizaveta realized that her romantic relationships were being watched closely.

When young Peter II ascended to the throne, Elizaveta and him became really close. There were rumors that Peter II was even in love with his young aunt; at least, they spent a lot of time together – going on hunts and picnics. There’s also an opinion that their marriage was planned, but the Church wouldn’t allow such close relatives to marry.

Peter II

The HermitageDistinguished noblemen Menshikov and Dolgorukov, who practically ruled for Peter II, plotted and competed for influence; they were scared by the close relationship of the young man with Elizaveta. They were afraid of her influence over him and, subsequently, were afraid to lose power; they planned to beneficially marry young Peter with one of their daughters. However, Peter died early, unmarried.

The first of Elizaveta’s unsuccessful courtships happened while he was still alive. First, she had a relationship with Major-General Alexander Buturlin, then with a сourtier named Sergey Naryshkin. Peter II exiled and disfavored them both. Either because he was jealous of them and Elizaveta together or he was under the influence of his advisors.

After the untimely death of young Peter II, Anna Ioannovna, Peter the Great’s niece, was put on the throne out of turn. During her rule, Elizaveta received proposals from foreign princes, but, feeling the competition, Anna refused them all. She condemned Elizaveta, who was almost 30 already, to an unmarried life.

The next big love of Elizaveta was Alexei Razumovsky, who came from the Zaporozhian Cossacks. It was speculated that he was almost the most handsome man in the entire Russian Empire. Razumovsky helped Elizaveta both carry out a palace coup and ascend to the throne, after which he received high ranks and the title of Count.

Alexei Razumovsky

(CC BY-SA 4.0)It was him whom, as per legend, Elizaveta secretly married in the village of Perovo near Moscow in 1742. The church kept the “evidence” for a long time – special ritual fabrics – “veils”, allegedly embroidered by Elizaveta herself. Then she purchased the entire village and built a palace there for Razumovsky.

Elizaveta saw no purpose in revealing her marriage to the public – she was already over 30 and her marriage with a man from not a very noble family could outrage the gentry. Besides, Razumovsky could have his own claims for power.

It was believed that, under Elizaveta, favoritism reached a large scale for the first time: Razumovsky enjoyed unlimited power, strongly influencing the empress and her decisions.

Apart from the secret wedding legend of Elizaveta, there were other rumors – about her children with Razumovsky. Although the empress officially never had heirs, contemporaries noted that the couple could have had a son and a daughter.

It was speculated that the daughter, known as Princess Tarakanova, was forcibly tonsured into a nun and lived in Moscow’s Ivanovsky Convent until her death. There were a lot of impostors, too, who later claimed to be the children of Elizaveta and Razumovsky.

One of such impostors was arrested and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress by order of Catherine the Great. Officially, Elizaveta was an unmarried lady until the end of her days.

Konstantin Flavitsky. Princess Tarakanova

State Tretyakov GalleryThe 40-year-old empress had another young favorite – Count Ivan Shuvalov, who, under her, became an educator and founded Moscow University and the Academy of Arts. However, until her death, she was close with Razumovsky.

Portrait of Catherine the Great by Dmitry Levitsky

Novgorod Museum-ReserveThe list of real and supposed favorites of Catherine stands at about 20 men. The amorous nature of the empress gave birth to rumors about unbelievable depravity that was happening at court.

Catherine the Great was the wife of Peter III, the heir of Elizaveta Petrovna that the latter chose herself. Peter III was the son of her older sister Anna (and a grandson of Peter the Great). As such, Elizaveta tried to mend the disrupted succession order.

Peter III. Portrait by Lucas Conrad Pfandzelt

The HermitagePeter grew up in Germany – and he wasn’t interested in Russia or power (or his German wife). Nonetheless, the imperial couple gave birth to an heir – future Emperor Paul I (as unpopular as his father). Later, they also had a daughter, who died in infancy. Peter III accepted the child, but was openly doubting himself being the father. According to the most popular version, Catherine gave birth to her daughter from her lover, future Polish King Stanisław Poniatowski.

Peter III had a reputation as a strange man and pursued a very unpopular policy, so Catherine, with the help of the nobility – and especially her favorite Grigory Orlov – carried out a palace coup in 1762.

Grigory Orlov. Portrait by Fyodor Rokotov

State Tretyakov GalleryPeter was arrested and, soon after, died under mysterious circumstances. Using the precedent when Catherine I became empress after the death of her husband, Peter the Great, Catherine the Great seized the throne after the death of hers.

What’s interesting is that just several months before ascending to the throne, Catherine (in secret from her husband) gave birth to a child from Grigory Orlov. The empress didn’t really try to hide her illegitimate son known as Alexei Bobrinsky – she bought estates and palaces for him. His brother Paul I later even gave him the title of count.

Alexei Bobrinsky

The HermitageGrigory Orlov was Catherine’s favorite for more than 10 years and the empress even wanted to marry him after ascending to the throne, but she was talked out of it. Later, she had other lovers and Orlov was disfavored from the palace.

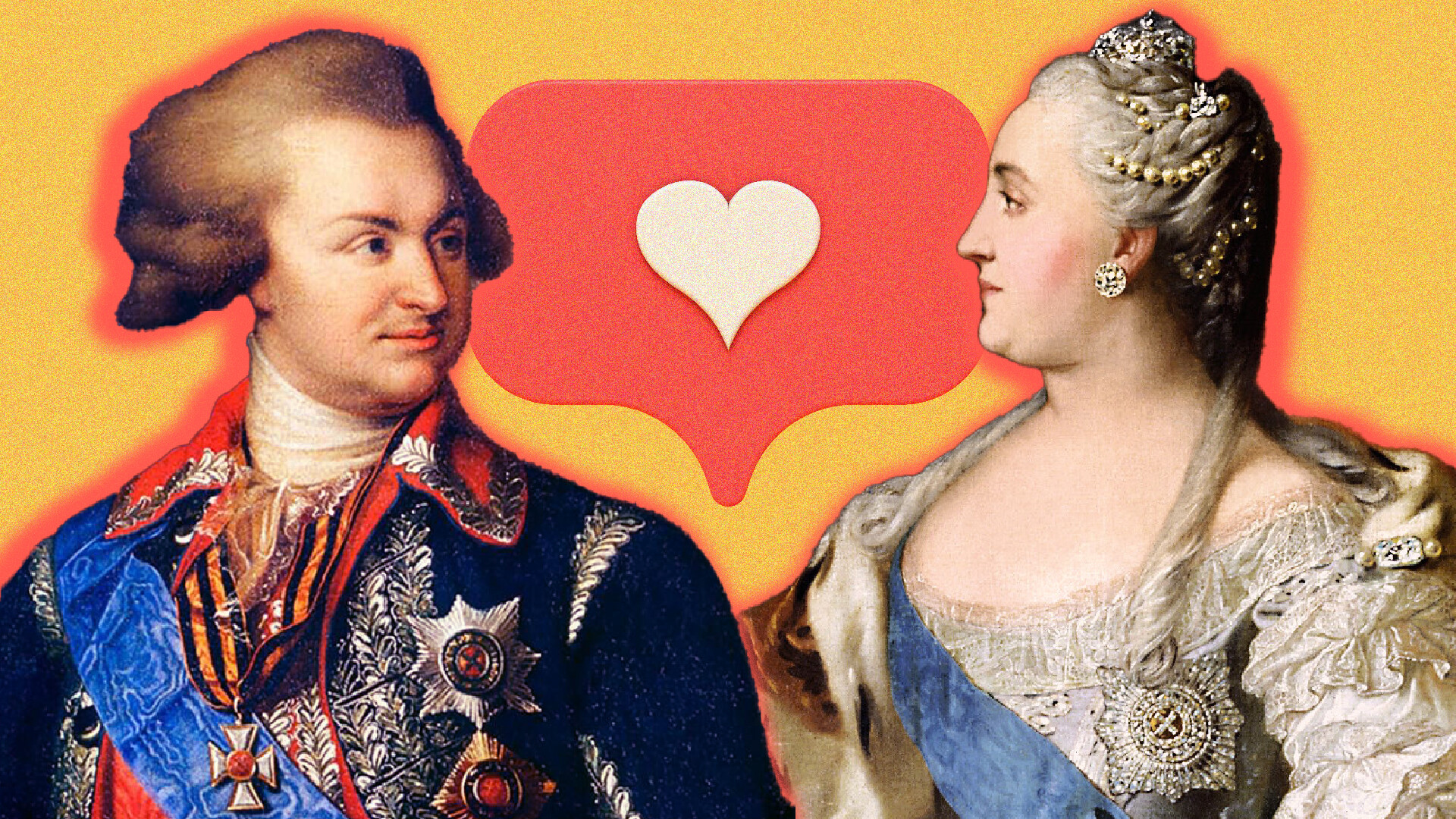

Her next favorite – and, apparently, Catherine’s big love – was Prince Grigory Potemkin. He was 10 years younger than the empress and was conquering new territories for the Russian Empire for her.

Grigory Potemkin. Portrait by Johann Baptist von Lampi the Elder

Public DomainTheir secret wedding took place in either 1774 or 1775. Many contemporaries believed that the wedding wasn’t just a rumor and truly happened. Potemkin enjoyed colossal influence and power, because of which he often had fights with the empress. She understood that he couldn’t claim power, so, despite their love connection being so open, she didn’t announce him as her husband.

There were rumors that Catherine even gave birth to a daughter from Potemkin, a certain Elizaveta Temkina, who he introduced as his ward. However, many historians believe that it’s unlikely that Temkina was Catherine’s daughter, since the empress at that moment was older than 45.

HBO shot a fairly credible show about the relationship between Catherine and Potemkin – Catherine the Great starring Helen Mirren.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox