Disclaimer: The phenomenon of ‘thieves-in-law’ still exists today. However, the habits and laws of thieves have changed over time. This article describes the thieves’ code of conduct that was developed in the Soviet period - and which is still considered to be the ultimate benchmark.

Prison No. 2 of the Vladimir Region Federal Penitentiary Service.

Stanislav Krasilnikov/TASSFor thieves-in-law, the state was the opposite of freedom and independence. Hence the ban on any form of cooperation with state authorities and public institutions. The ban was probably derived from the idea that a head of the criminal underworld had to be able to make his decisions independently, only guided by the thieves’ code of honor and interests of the criminal community and could never succumb to the pressure or orders from anybody, especially the state.

In practice, the total rejection of the state by the thieves-in-law translated into a set of specific prohibitions: never plead guilty to charges, never give any statement to the prosecution, never appear as a witness in court, never pay taxes, never make deals with a prison administration, etc.

Inmates of the penal colony.

Valery Sharifulin/TASSThe above-mentioned core principle of the criminal underworld translated into many other related rules and guidelines that thieves-in-law pledged to abide by. Among them was the ban on having expensive property or any other possessions like cars or houses.

According to the criminal code, a thief had to live a modest life and retain a low profile that would not put him on the radar of the authorities. Being a boss of other criminals, he also had to be more concerned with solving the problems of his adherents, rather than with his personal enrichment.

A thief’s way of life had to be ascetic to the point that it was prohibited for thieves to be registered at any particular place in the country.

In the high-security penal colony No. 1 in the settlement of Sosnovka.

Stanislav Krasilnikov/TASSNeither should thieves-in-law form lasting relations with any woman. Marital relationship was believed to be a luxury reserved for ordinary people. A married person with a family was vulnerable to pressure and thieves had to be immune to this. Also, it is believed that a family would take too much of thieves’ valuable time that had to be wholly dedicated to the problems of the criminal underworld.

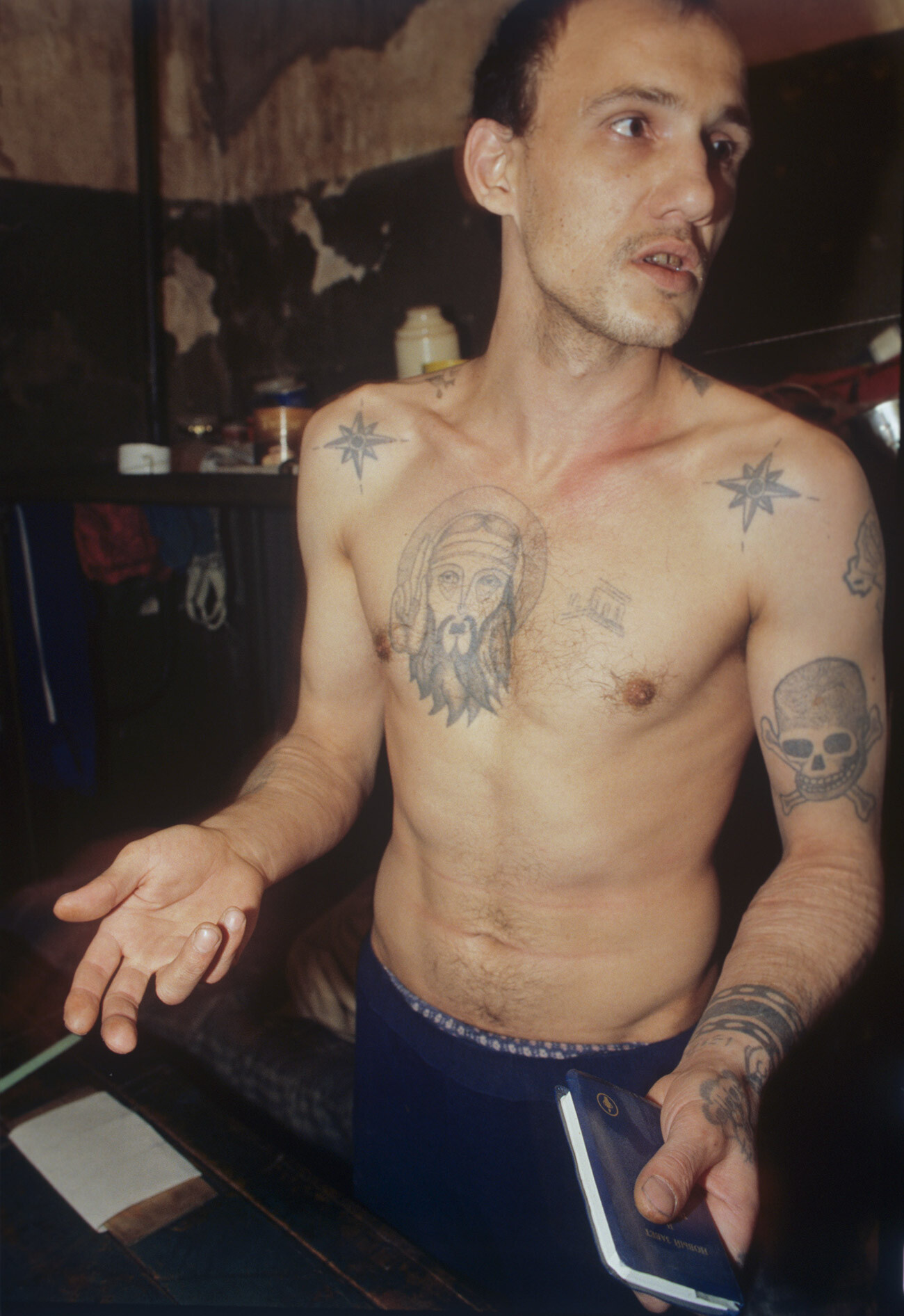

Vologda prison. Convict serving time in prison.

Vladimir Vyatkin/SputnikA would-be criminal had to serve time in jail to earn the privilege of being named a ‘thief-in-law’. Even those criminal bosses who had already been crowned as thieves-in-law (the very ceremony takes place in prison) often returned behind bars when it was time to replace another high-profile thief whose term was coming to an end.

This rule ensured that the complex prison hierarchy always remained intact, as the thieves, who were at the top of the prison caste system, maintained control over the inmates. Paradoxically, a thief could never confess to a crime he was charged with, because confession required cooperation with the prosecution.

A prisoner passes through the gates of a prison in Harp on the Yamal peninsula in the far north of Russia in this undated picture.

APThieves could not have any occupation besides fulfilling their responsibilities in the criminal underworld. In penitentiary institutions in Russia, work was considered to be a lowly occupation not suitable for the thieves-in-law. Instead, it was reserved for the most widespread caste in the Russian penal colony system, simply known as ‘muzhiki’.

This rule derived from the belief that working for the benefit of someone implied the subordinate position of the worker. When crowned, thieves pledged to only earn by stealing from the rich.

Mob boss Boris Nayfeld poses for a picture at the Russian Baths in the Brooklyn borough of New York, Thursday, Jan. 18, 2018.

APIt is believed that a legitimate thief-in-law had to exercise his authority without resorting to arms. This implied that his authority was based on respect for fellow criminals and not the mere threat of violence. If the need arose, however, a thief-in-law could always entrust the dirty business to his subordinates.

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox