“I remember carts being pulled down the street from which dangled the bare legs and arms of members of the labor army who had died of hunger and cold.” The recollections of Soviet Germans who survived the so-called ‘trudarmiya’ (abbreviated form of “trudovaya armiya” - i.e. ‘labor army’) are full of such grim stories. The ‘labor army’ was one of the ways the Soviet authorities dealt with those branded as a “punished nation” or “transgressor nation”. In addition to Finns, Romanians, Hungarians and Bulgarians, they were primarily Soviet Germans. Blame for the actions of their historical homelands was placed on their shoulders.

Germans deported from Volga Region

Archive photoThe ‘trudarmiya’ began to be formed in September 1941. The reason for its appearance was simple: The Germans deported from Volga Region and Crimea to Siberia and Kazakhstan at the beginning of the war lived in terrible conditions and were on the verge of despair. On the one hand, this tension carried with it a potential danger. On the other, the Soviet Union needed a workforce to keep industry going in wartime. Both problems could be solved by sending the Germans to factories for forced labor.

On January 10, 1942, the State Defense Committee passed a resolution - marked “top secret” - “On the procedure for using German resettlers of conscription age between 17 and 50 years old.” Men fit for physical labor were to be sent to logging camps or to railway and factory construction sites. For this, Germans were to report to assembly points “in good winter clothes with a supply of linen, bedding, a mug, a spoon and sufficient food for 10 days” - demands that could hardly be met by people summarily evicted from their homes under the deportations. For failure to turn up or for desertion, they faced capital punishment - they could be shot.

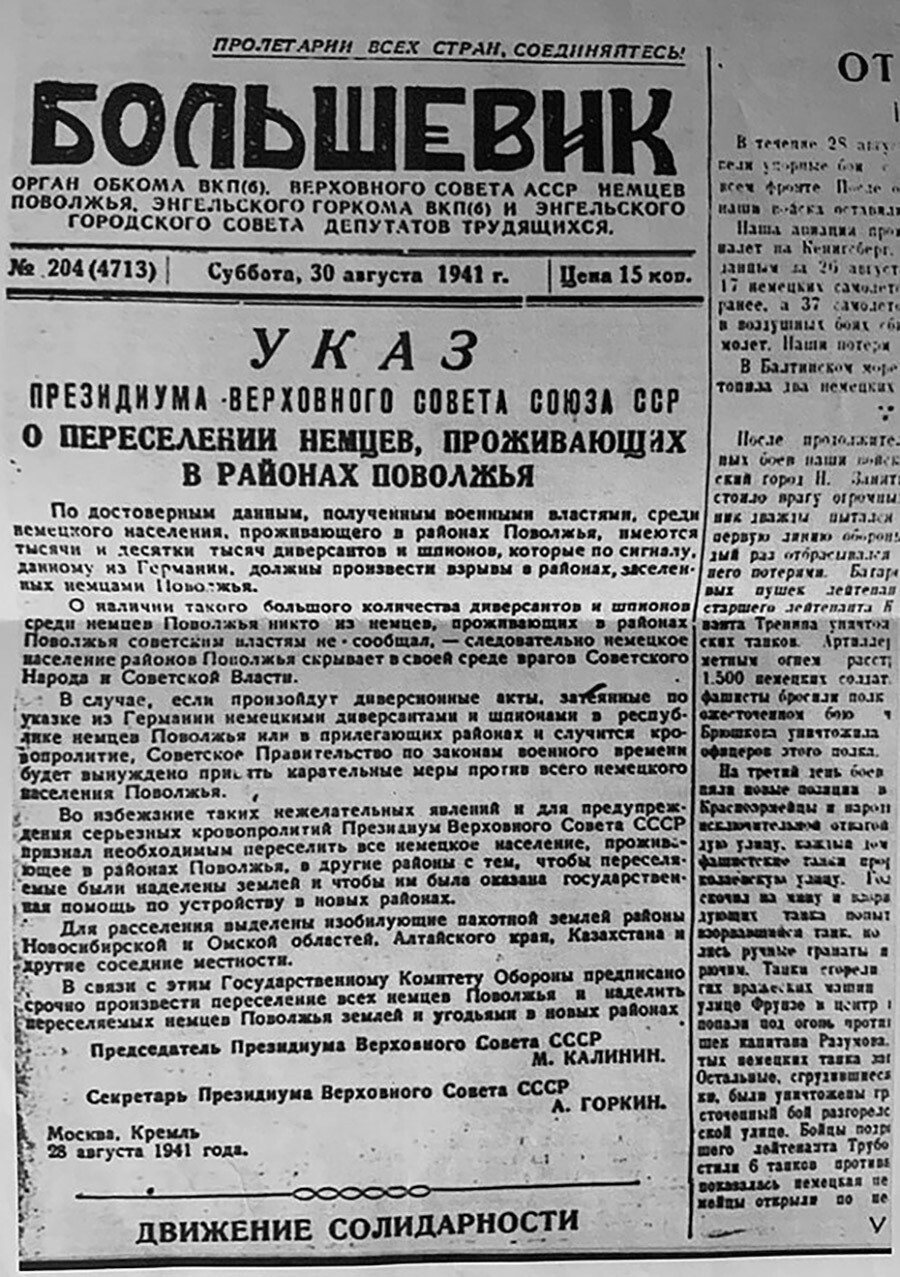

Decree on the resettlement of the Volga Germans in the Bolshevik newspaper, 1941

Archive photoThere is a theory that those who had been mobilized began to use the term ‘labor army’ themselves to describe the forced labor they were subjected to. Some historians argue that the term did not feature in official documents: It was used by people who didn’t want to equate themselves with prisoners in the way the Soviet authorities were doing. Others point out that the phrase can be found in documents drawn up by local officials, such as heads of labor camps and construction sites: While the central authorities wanted to avoid evoking associations with the Labor Army of the 1920, in which Red Army soldiers served after the Civil War (1917-1922), managers at a lower level could not find any other description for what was happening.

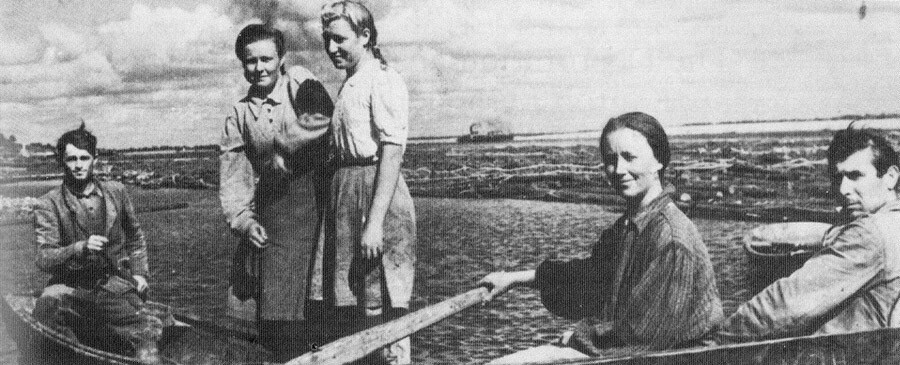

Germans who were forced to leave their houses

Archive photoHistorian Nikolai Bugai describes the so-called ‘labor army’ as a combination of “military service, production activity and Gulag-style confinement”. Many former “labor army Germans” recall terrible living conditions in the “zones”: “…the place where we ended up was a real concentration camp,” recalled Mikhail Schmidt, a native of Kharkov. “I was put in a general team digging a waste-water disposal trench for the ‘Ural’ plant. The ground was frozen, with temperatures down to -35°C. We had to gouge out the ground with metal bars and sledge hammers - it was hard work. Many did not survive.” Albert Henrichs, another German mobilized to the Urals, recalled: “Our living conditions were identical to those of prisoners […] It was particularly scary to see one another in the banya: Undressed, we were like skeletons.”

Lack of food and clothing and long hours of hard work in a harsh climate with no way to keep warm in winter - in these harsh back-breaking conditions the ‘trudarmiya’ members were held to the highest standards in their work. Discipline was also strictly enforced and the camps were fenced with barbed wire and guarded and patrolled by armed staff who often treated the mobilized workers with open hostility and even hatred.

Mikhail Schmidt recalled: “In winter, our team approached the work shift checkpoint, where we always had to wait a long time in freezing temperatures. One inmate fell to the ground and was lying there. A security guard went up to him, kicked him and said: ‘Get up, you fascist son of a bitch!’ - but the man was already dead.”

But, there were also sometimes people among the staff and local residents who took pity on the Germans and helped them survive in these horrific conditions: “…there are kind people everywhere. One security guard would let us out on summer evenings and we would go to the fields and find turnips and other vegetables, then we’d boil and eat them. In spring, we used to find frozen potatoes,” says Maria Sabot, a native of Volga Region.

One of the first Soviet Germans in the labor army in the Urals

Archive photoSince the need for labor was growing, the mobilization continued and more and more sectors of the economy recruited members of the ‘labor army’. By the end of 1942, other nationalities had been sent to the “labor front” - Finns, Romanians, Hungarians, Bulgarians, Italians and other “transgressor nations” whose historical homelands were fighting on the Nazi side.

Men and boys aged 15-55 and women between the ages of 16 and 45, except if they were pregnant or had children below the age of three, were liable to be called up. “I remember the children running after the cart, crying and pleading: ‘Mommy, don’t leave me, take me with you!’ But the soldiers drove the women away. The children stayed with relatives or were put in children’s homes,” recalled Emertiana Frank, who worked at the Uralsky Paper Combine.

Many members of the labor army regarded what was happening to them as an injustice, notes historian Arkady German. But while the older generation, which had already lived through the Germanophobia of the tsarist regime, the horrors of the Civil War and the purges of the 1930s, was used to such upheavals, for the young, the brutality of the authorities came as a shock. Young people reared on Socialist ideals “simply couldn’t understand how they could be equated with ‘fascists’. […] They were affronted by the situation and seized by a desire to demonstrate their loyalty and patriotism through hard work and exemplary conduct.”

Soviet Germans in Siberia, 1943

Archive photo“We worked in a close-knit fashion in the belief that our efforts were also making a contribution to the front and we saw victory as offering the hope of being able to return home and see our families again […] it is said that, at Christmas, the labor army women sang carols very quietly on the factory floor and prayed to God to intercede in ending the infernal war as soon as possible and bring justice to those who weren’t guilty of anything,” is how Emertiana Frank described her feelings. Many of those who were mobilized resisted, however, refusing to work and even attempting to flee. Those who were caught were brought back, tried and frequently sentenced to death.

Finnish settlers in Yakutia

Archive photoThe ‘trudarmiya’ was not disbanded at the end of the war against fascist Germany - this only happened in 1947. Over 316,000 Soviet Germans had been mobilized for the ‘labor front’ during the war years, according to some data. The survivors could not return to their places of origin, however: They were only permitted to go back to the locations where they had been resettled prior to the start of mobilization.

On November 26, 1948, a decree of the USSR Supreme Soviet Presidium was issued ‘On criminal liability for abscondments from places of compulsory and permanent settlement of persons resettled to distant regions of the Soviet Union during the Great Patriotic War’. Everyone who had been resettled was “tied” by the decree to their new places of domicile - “in perpetuity, without the right of return”. Any of the so-called “special settlers” who left without authorization were to be regarded as absconding and those who took the risk of breaching the terms of the decree faced 20 years’ hard labor.

Germans, exiled to the Russian North, 1948

Archive photoThe new measure made it possible for people to be reunited with their families, including children who had been left in the care of collective farms or with relatives who were unable to work. Not everyone was lucky and some families remained divided: “There are mothers here in Solikamsk who still haven’t found their children. They ended up in children’s homes, where they were given different first names and surnames. Sometimes the parents do finally trace their children, but are rejected by them: ‘You aren’t my mother!’,” related ex-labor army member Edvin Grib in the 2000s.

Emertiana Frank recalled those times as not just a period of fresh worries, but also new hope: “The special commandant’s office once again featured in our lives, and, once again, there were hopes and fears about what the future held in store for us. But life took its course and we carried on working, settling down and starting families.”

The special resettlement regulations were repealed in 1955 after the death of Joseph Stalin, but the Soviet Germans neither got their property back nor received the right to return to their home regions. Nor did this happen under Nikita Khrushchev in 1964, when a new USSR Supreme Soviet decree was promulgated. It recognized the accusations against the Germans as unjust and as having been “a manifestation of arbitrariness in the context of the Stalin personality cult” - but, as the Germans themselves and the people who were now living in their previous places of domicile were already settled in their new homes, everything was to remain as it was.

City of Engels in Saratov Region, 1970

Yevsyukov/SputnikThe restrictions were only lifted in 1972 when the Presidium resolved that the Germans and other nationalities who had previously been deprived of their freedom of choice should “enjoy, like all Soviet citizens, the right to choose their place of abode throughout the territory of the USSR”.

But, even then the authorities did not want the Germans to return to their previous places of domicile and did not encourage people to move home. The initiatives of Germans to set up a national autonomous entity - along the lines of the autonomous republic that had existed in Volga Region from the end of the second decade of the 20th century to 1941 - never came to anything either.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox