What's life like for ethnic Germans living on the banks of the Russian Volga?

This is a town with streets so straight they look as if they were drawn by a rake. The street and shop signs are in gothic Cyrillic, solid brick houses with hipped roofs and smoking chimneys fill the town, and there is an old Lutheran church in the central square. Welcome to the town of Marx (or Marks), which is located in the north of Saratov Region and was founded in 1765 by German settlers who had traveled to far-away Russia at the invitation of Empress Catherine the Great under the name of Kathrinenstadt (or Baronsk).

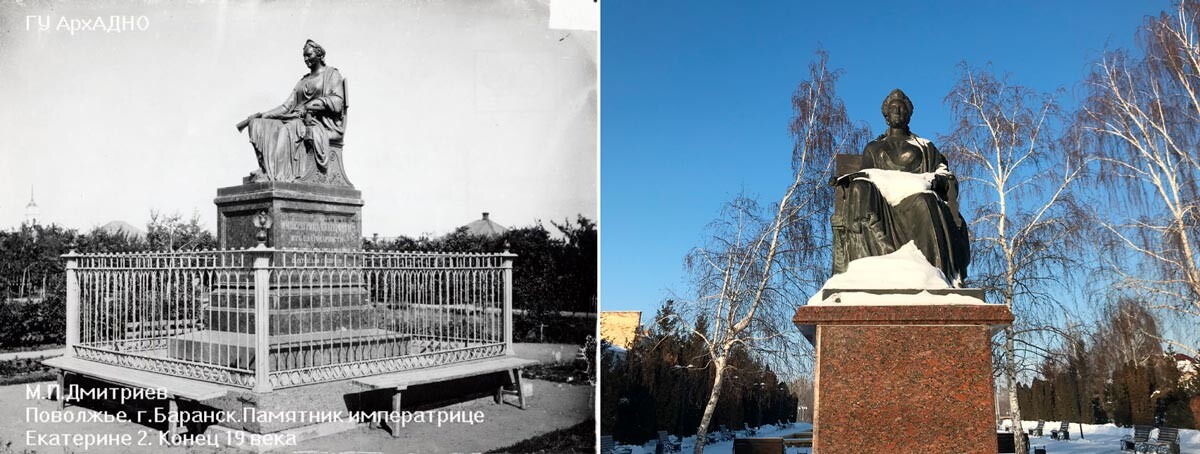

Kathrinenstadt in 1894.

Audiovisual documentation archive of Niznhy Novgorod/RussiainphotoIn 1918, the Bolsheviks began renaming places to sound less bourgeois and more Soviet, and Kathrinenstadt became Marxstadt. However, in 1942, a year after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union and the Volga Germans were deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan, the town began to be called simply Marx. Before the deportation, ethnic Germans made up almost 90 percent of the local population, while the remaining 10 percent were Russians. Today the ratio is exactly the opposite—the current population is around 30,000 people.

Although the Volga Germans were granted the right to return to these territories a long time ago, few have actually done so. Some stayed in Siberia, where there are even two German ethnic regions, while others moved to Germany. Nevertheless, some of their descendants have not only returned to their homeland, but also tried to preserve and revive the distinctive cultural and historical heritage of the old settlements.

A church overlooking a Lenin monument

Lutheran church in central Marx and the monument to Vladimir Lenin.

Anna Sorokina“My grandparents were from Mariental [since 1942, the settlement of Sovetskoye]. They always had very fond memories of the Volga and wanted to return there,” says Yelena Kondratievna Geidt, who has headed a public association of Russian Germans in the Marx District for almost two decades. In Soviet times, her entire large family lived in Kazakhstan and continued the traditions of the Volga Germans there.

“I have been a Catholic since childhood, although in my Soviet youth I was a secretary of the Komsomol organization. But at home we observed Catholic rites and celebrated our holidays, because churches were banned.”

Yelena Geidt.

Anna SorokinaYelena is one of the few people who still speak the old dialect of the Volga Germans, although she does not really have anyone to use it with.

“In the mid-1980s, we returned to the Volga. Then my parents, as well as sisters and brothers, left for Germany, while my husband and I stayed,” she says.

In 1972, the right to free movement was restored to all displaced Germans in the USSR and they were allowed to return to their homeland, but not to the exact locality where they used to live (presumably in order to avoid property claims). By the 1980s, a period of late socialism and more liberal attitudes, the ethnic Germans began returning to the Volga region. However, they were not always welcomed by the local population there, and many Volga Germans left for Germany, taking advantage of West Germany’s 1953 law on repatriation and increased freedoms that began in the USSR with perestroika.

“Those who left knew the language well and integrated into the German environment, while I really fell in love with the Volga region and especially Marx and stayed,” Yelena says.

The historical and modern monuments to Cathrine the Great.

Maxim Dmitriev/Audiovisual documentation archive of Niznhy Novgorod/Russiainphoto; Anna SorokinaWhen the Germans originally began settling empty land in the area all those centuries ago, their settlements were clearly divided into Lutheran and Catholic ones. Marx was the only town where members of the two communities lived side by side, and the town always had both a Lutheran church and a Catholic church. Needless to say, the Soviet period left its mark on the town's historical appearance and now opposite the Lutheran church there is a monument to Vladimir Lenin and the headquarters of the local administration. In the post-Soviet years, a monument to Catherine the Great was erected behind them as well.

In Marx, some street names are written in gothic Cyrillic. Also, central streets are called "lines", like on Vasilievsky Island in St. Petersburg, which was the home for many Russian Germans, too.

Anna SorokinaThe part of the original Volga Germans' legacy that has best survived is cuisine. Local residents, both Russians and ethinc Germans, still cook Kräppel donuts, Kraut and Prai pork and, of course, the traditional Rivel Kuchen pie sprinkled with flour mixed with sugar and butter.

History enthusiasts

“In the early 2000s, we were a closed community,” Yelena says. “We studied the language, sang songs. And today's young generation did not even know the German history of Marx—they thought that all these buildings were built by German prisoners of war... Then we began to work with local historians, win grants and publish books.”

The river terminal of Marx and the monument to Fridtjof Nansen, who organized grain expeditions in 1921-1922 to help starving children of the Volga region.

Anna SorokinaThanks to these efforts, locals began to realize that the Volga Germans are practically an indigenous ethnic group in Russia and grew to appreciate their work ethic and culture.

“We have German classes taught by a teacher from Germany and German ensembles,” Yelena says. "We cooperate with all German cultural centers in the Saratov Region, and there are 22 of them here. These social projects are not only for Germans—they are for all residents of the town.”

Christmas celebration in the Lutheran church in Marx and at the Engels (Saratov suburb) Russians-Germans center.

Anna Sorokina“Of course, I knew about the Volga Germans from childhood,” says Alexander Shpak from the Volgograd Region. “My mother lived in the village of Niedermonjou [present-day Bobrovka] in Marx District, but there was not a single mention of the Republic of the Volga Germans [in the early Soviet years and before the deportation, there was a state entity called the Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic of the Volga Germans that occupied part of the modern Volgograd and Saratov regions along the Volga]. This is why I had to collect information bit by bit.”

Russian-Germans center in Marx.

Anna SorokinaIn 2009, Alexander went on a tour of the former German cantons (as the German districts were called in the early Soviet years) and put together an interactive map that lists old place names dating back to the Russian Empire and their present-day versions. Thus, Basel became Vasilievka, Strassburg became the village of Romashki, Mannheim became the village of Marinovka.

Zurich in Russian provinces

Lutheran church in Zorkino.

Anna SorokinaThe former German villages stretch along the Volga for hundreds of kilometers. Nowadays, there is a road here as well as gas stations and cafes, but 250 years ago it was “steppe all around,” as one famous Russian song goes.

The former German colonies have dozens of old Lutheran and Catholic churches, most of which are abandoned today. Interestingly, this sad fate befell them not during the Bolsheviks' fight against religion in the 1930s but during the economic crisis that followed the collapse of the USSR. The Lutheran church of Jesus Christ in the village of Zorkino (near Marx), which many still call Zurich, was luckier. It has not only been restored but has become one of the main reminders of this area’s German heritage.

The transformation took place in 2015 thanks to Karl Loor, a businessman from the town of Stary Oskol in the Belgorod Region. His ancestors came from the local Zurich, and he decided to help his native village.

Now the church is lined inside with real wood, and services are held here on Sundays and religious holidays as well as regular organ recitals. Nearby Loor has built a small guest house.

Inside the church.

Anna SorokinaBut this is just one restored church, and the German Volga region has far too many still awaiting restoration. For example, local activists in the village of Lipovka—two hours from Zurich and formerly called Schäfer—are trying to prevent the destruction of an old church that dates back to 1877. They hope that another Loor will come forward.

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox