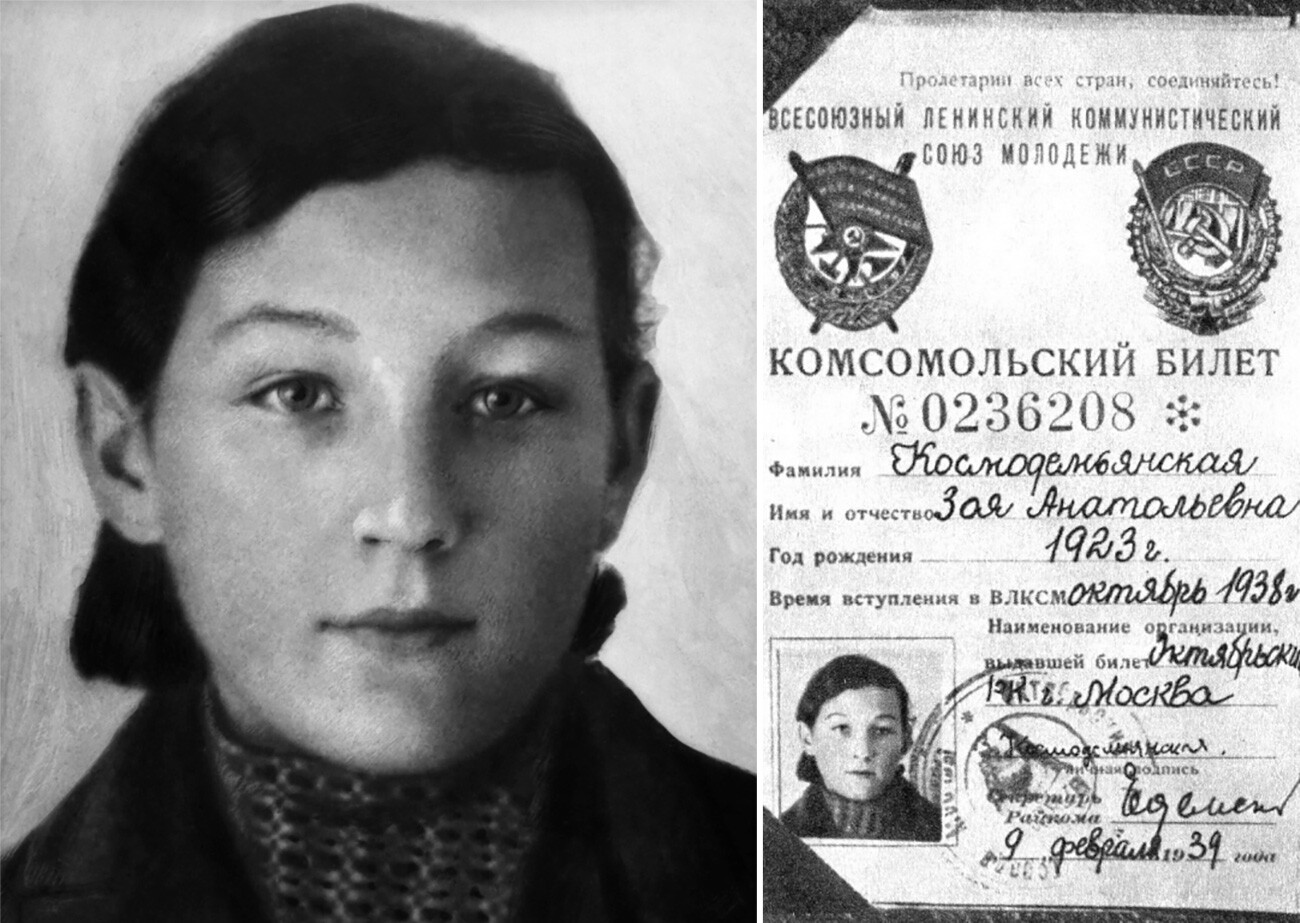

In June 1941, when Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was finishing 9th grade in school, Nazi Germany invaded the USSR. In the fall of the same year, German troops approached Moscow. Government bodies and industrial enterprises were evacuated from the city. However, Kosmodemyanskaya decided to enlist in a squad of Komsomol volunteers at the end of October 1941.

On November 17, 1941, the ‘Stavka’ of the Supreme High Command issued an order to destroy settlements on the territories occupied by the Germans.

To carry out such actions, new personnel was required. They were recruited in advance from the ranks of young volunteers, even before the issuing of Stalin’s order. These young people were enlisted in the military unit №9903, one of the most secret in the Red Army. That was the Central intelligence and sabotage school at the Komsomol Central Committee.

And that’s where Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya ended up. Along with other volunteers, she studied active reconnaissance of the enemy troops, road mine-laying, bridge destruction, arranging ambushes on roads, destruction of warehouses and communications infrastructure, creating partisan squads and much more.

Battle of Moscow Oct.41-Jan.42: German tanks and infantry advanving onto a village in the district of Wolokolamsk / Klin. December 1941

Arthur Grimm/ullstein bild via Getty ImagesThe intelligence sabotage group where Zoya ended up was sent to Volokolamsk (100 kilometers west from Moscow). Her first successful combat mission was laying mines on the roads behind the enemy lines. Later, she participated in the elimination of a German motorcyclist, on whom staff documents and topographic maps were found.

Soon, Kosmodemyanskaya was sent to carry out sabotage in ten Moscow Region settlements. In the night from 27 to 28 of November, her group had to destroy a German radio intelligence field post, located in the stables in the village of Petrishchevo – as well as houses, where German soldiers were stationed. Only three reached the village – group leader Boris Kraynov, Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya and Komsomol organizer of the intelligence school Vasily Klubkov.

During the sabotage operation, the Germans captured Kosmodemyanskaya, who still managed to destroy two houses and an enemy car with incendiary bottles, and Klubkov. The girl was handed to the Germans by the inhabitants of the occupied village, who were collaborating with the occupants. Despite cruel torture, she didn’t reveal her real name during questioning – she called herself ‘Tanya’ – and didn’t reveal information on other saboteurs.

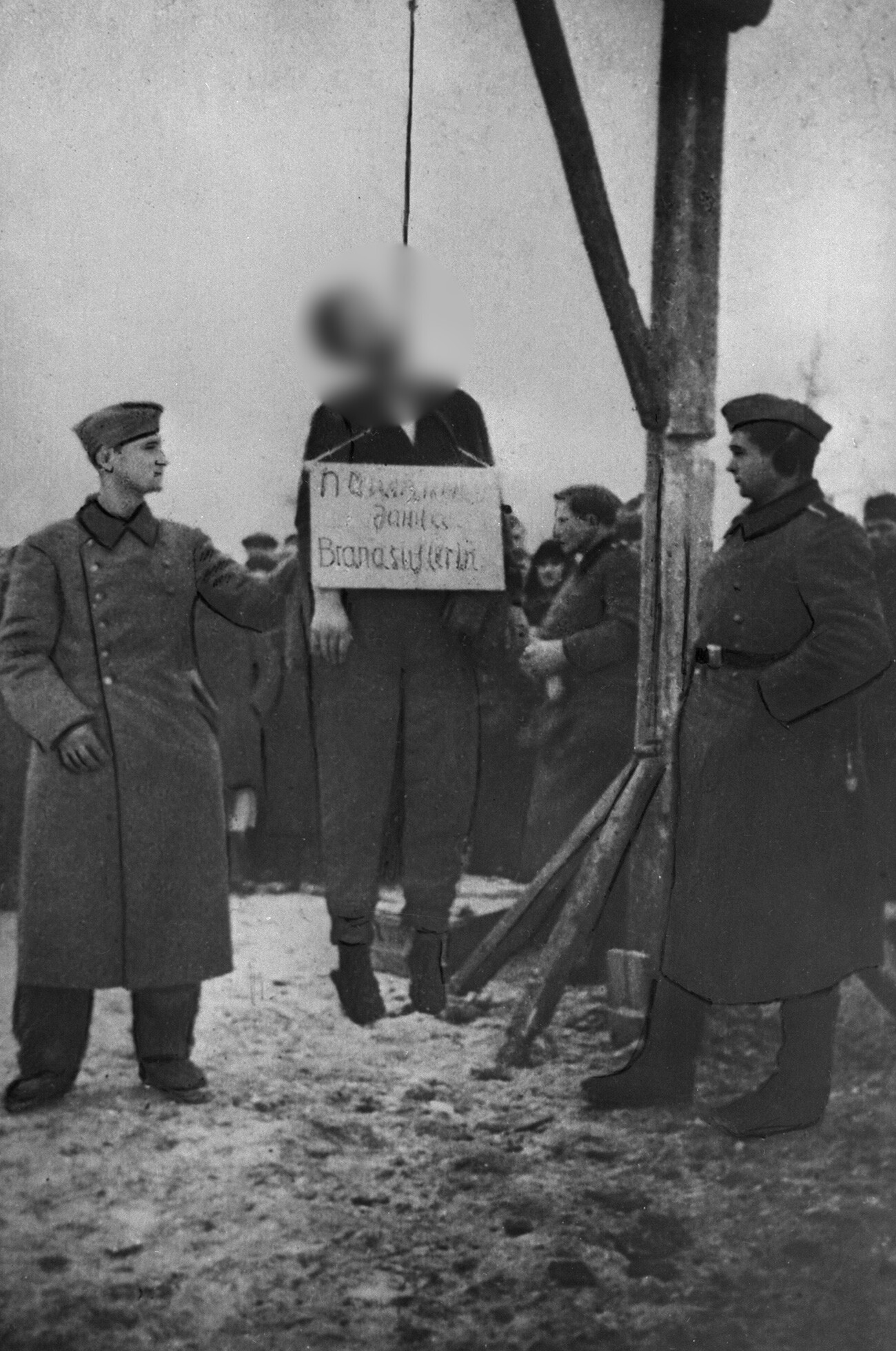

On November 29, 1941, she was executed by hanging. Her body with a sign that read “partisan” remained on the gallows for more than a month and was only buried on January 1, 1942. At the end of January, Petrishchevo was liberated by Soviet troops.

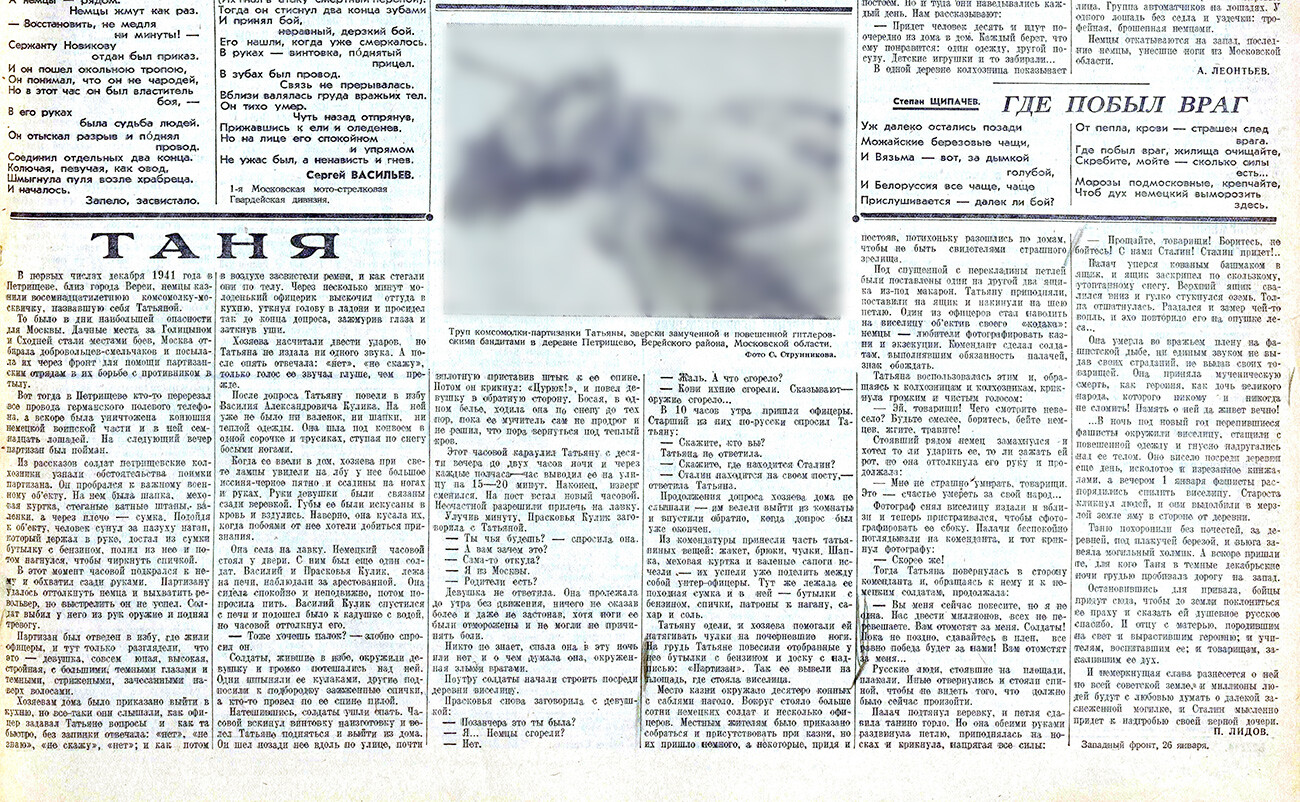

The deed of Kosmodemyanskaya was conveyed to the Soviet people by war journalist Pyotr Lidov. He was writing about the liberation of Moscow Region from the Germans and, in one of the villages, heard the story of a girl who delivered a brave speech before her execution.

Lidov visited Petrishchevo several times; he questioned the locals, received access to secret documents about sabotage groups, but couldn’t find any ‘Tanya’. The identity of the girl was established only after exhumation, by photographing the body and publishing these photos on January 27, 1942. On this day, the main newspapers at the time, ‘Pravda’ and ‘Komsomolskaya Pravda’, featured Pyotr Lidov’s essay ‘Tanya’ and Sergei Lyubimov’s essay ‘We won’t forget you, Tanya’.

In his essay, Lidov cited the last words of the girl: “You hang me now, but I'm not alone. There are two hundred million of us. You can't hang us all. They will avenge me. Soldiers! Until it’s too late, surrender, victory will be ours anyway!”

On February 16, 1942, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet posthumously awarded Kosmodemyanskaya the title of Hero of the Soviet Union. On February 18, 1942, Lidov released a new essay titled ‘Who was Tanya’, where he publicly revealed the identity of ‘Tanya-Zoya’, as well as her bravery and resilience.

“We got our hands on non-commissioned officer Karl Beierlein, who attended the torture that Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya was subjected to by the commander of the 332nd Infantry Regiment of the 197th German Division, lieutenant colonel Röderer. In his testimony, Hitler’s non-commissioned officer, clenching his teeth, wrote: ‘The little hero of your people remained adamant. She didn’t know what betrayal was… She turned blue from the cold, her wounds bled, but she said nothing’,” Lidov wrote.

In the memory of Kosmodemyanskaya and her deed, monuments and memorial plaques were opened across the entire Soviet Union; schools, libraries and children’s camps, streets and villages were named after her. Even mountain peaks, asteroids and ships were named in her honor. And, of course, countless movies and poems, operas and songs were also dedicated to her.

Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya became the symbol of the heroism of the entire Soviet people. But, especially of partisans and saboteurs, who walked into their certain deaths for the rescue of the country’s capital. According to Klavdia Sukacheva, a veteran of the military unit №9903, 951 people perished from the 2,000-strong personnel of the unit, meaning almost every second member. Departing on a mission, they took no documents along with them and remained unidentified after death.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox