Female athletes at the sports parade

Anatoly Yegorov/MAMM/MDF

“Glory to equal rights for women in the USSR!”

Public domainFemale laborer demonstrations that shook Russia at the beginning of the 20th century were an important part of the Russian Revolution. Partially, that was the reason why Soviet Russia became one of the first countries in the world where women were completely equal with men in their rights.

“Woman is the great power of the Soviet state! Vote for the worthy deputes!”

Public domainThe Bolsheviks realized that women were important social capital and that they needed to closely work with them on the level of propaganda and education.

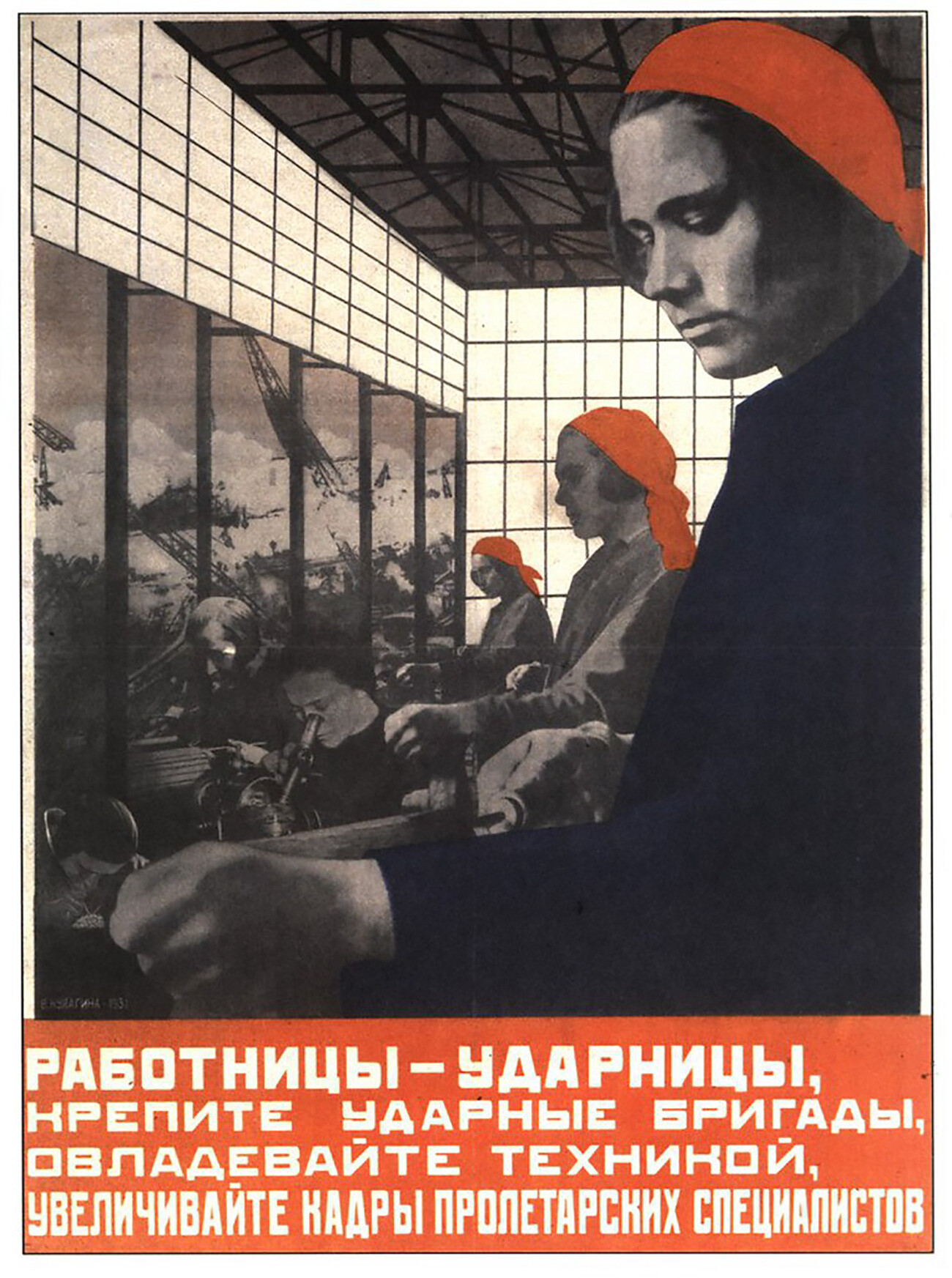

“Female shock workers, reinforce shock brigades, master technology, increase the cadres of proletarian specialists.”

Public domainIt was important to weed out “old regime” ideas from them – that they were the “weak sex” and that they had to stay at home with kids, serve their husbands and stay in “kitchen slavery” and in a perpetual cycle of home chores.

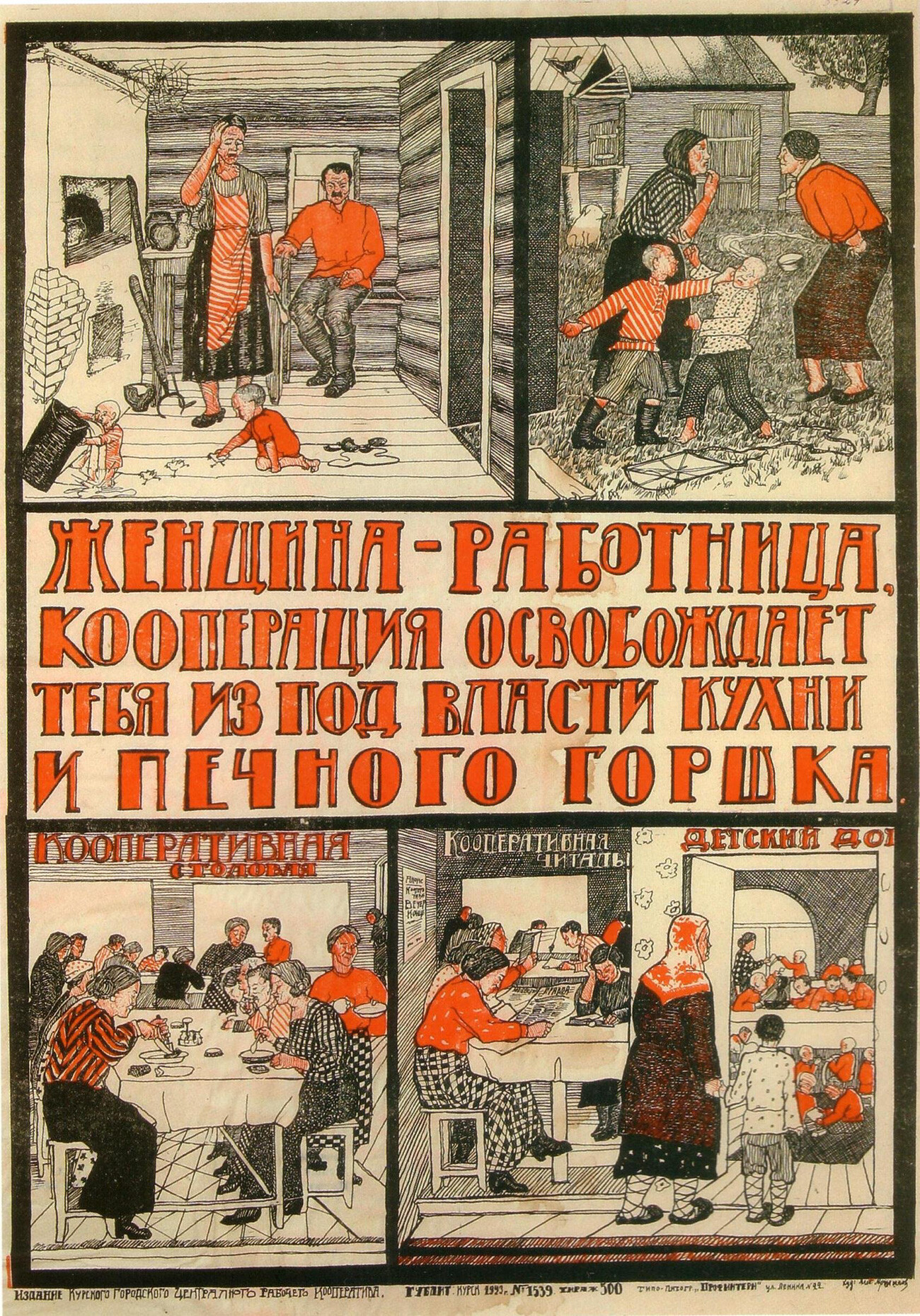

“Working woman - Cooperation frees you from the power of the kitchen and the stove”

Public domainDuring the very first months after the 1917 Revolution, decrees were signed, equaling the rights of women and men in salaries, in family and marriage matters. Women were entitled to an 8-hour workday, as well as to a vacation and pregnancy and childbirth benefits (Because of the fact that such a leave was established by a Soviet decree, this leave is still called the “decree” leave in Russia today).

Vladimir Lenin, leader of the Revolution, especially ardently advocated women’s rights (and, it seems, counted on their support). He supported the ideas of women’s congresses and conferences; he closely communicated with women revolutionaries, who were inspired by the ideas of women’s rights.

“Woman! Literacy is the key to your emancipation”

Public domainIn 1919, in the article ‘Soviet Power and the Status of Women’, Lenin wrote: “In the course of two years, Soviet power, in one of the most backward countries of Europe, did more to emancipate women and to make their status equal to that of the ‘strong’ sex than all the advanced, enlightened, ‘democratic’ republics of the world did in the course of 130 years.”

“Female worker, be in the first rows of the builders of socialism, raise your literacy and culture, enhance your qualification”

Public domainHe also believed that, “in no bourgeois republic (i.e., where there was private ownership of the land, factories, works, shares, etc.), be it even the most democratic republic, nowhere in the world, not even in the most advanced country, have women gained a position of complete equality”. And even the French Revolution couldn’t resolve this question, couldn’t give “the feminine half of the human race either full legal equality with men or freedom from the guardianship and oppression of men”.

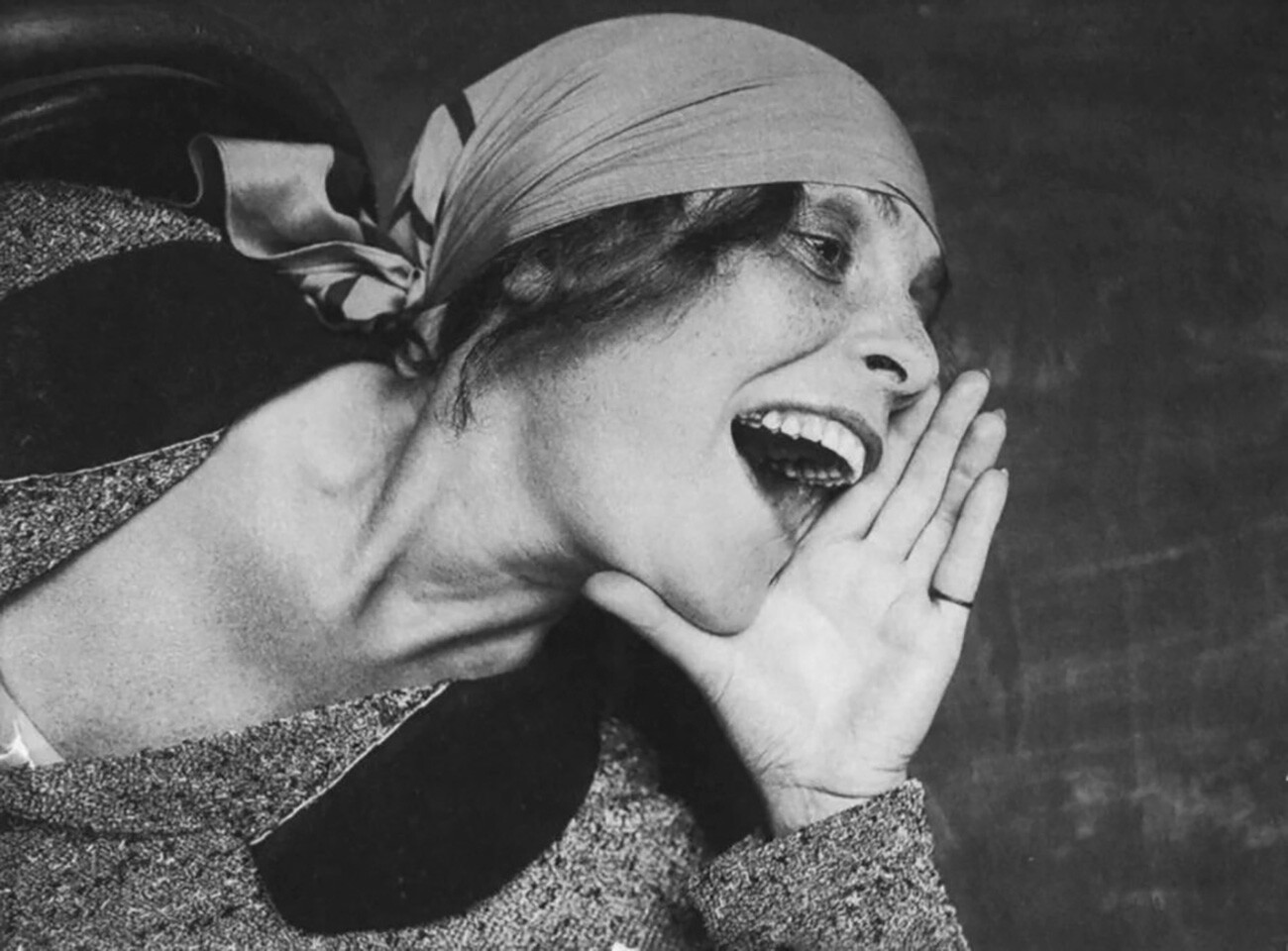

Lilya Brik, a photo for a publishing house advertising

Alexander RodchenkoEven before the Revolution there was an Agitation and Propaganda Commission in the Bolshevik Party among women workers and peasants. In 1919, a women’s department was created within the Communist Party or, as it was called, ‘Zhenotdel’, “for working among working women with the goal of fostering them in the communist spirit and to involve them in the socialist development,” as is written in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

Inessa Armand, the first head of Zhenotdel

Public domainThe first department head was Inessa Armand, an ally (and, possibly, a lover) of Lenin and an ardent revolutionary. She organized women’s communist conferences and fought against the traditional view of a family among women.

Alexandra Kollontai, Soviet politician

Public domainIn 1920, she was replaced in this position by Alexandra Kollontai, another famous revolutionary (and the first female minister in Russia and, later, female diplomat). She actively advocated women’s education, as well as promoted political agitation among women – for them to learn that the order had changed and now the country had new labor conditions and a new division of responsibilities in families.

First female police officer

Murom art and history museum/russiainphoto.ruAside from that, Zhenotdel dealt with a wide spectrum of social matters – it created committees to help sick and wounded Red Army soldiers and, during the Russian Civil War, it organized evacuation points. The women of Zhenotdel cared for orphans, opened boarding schools, organized public canteens, held subbotniks (volunteer unpaid work days). By the end of the 1920s, Zhenotdel had more than 600,000 delegates that organized the work of the department across the country and participated in various congresses.

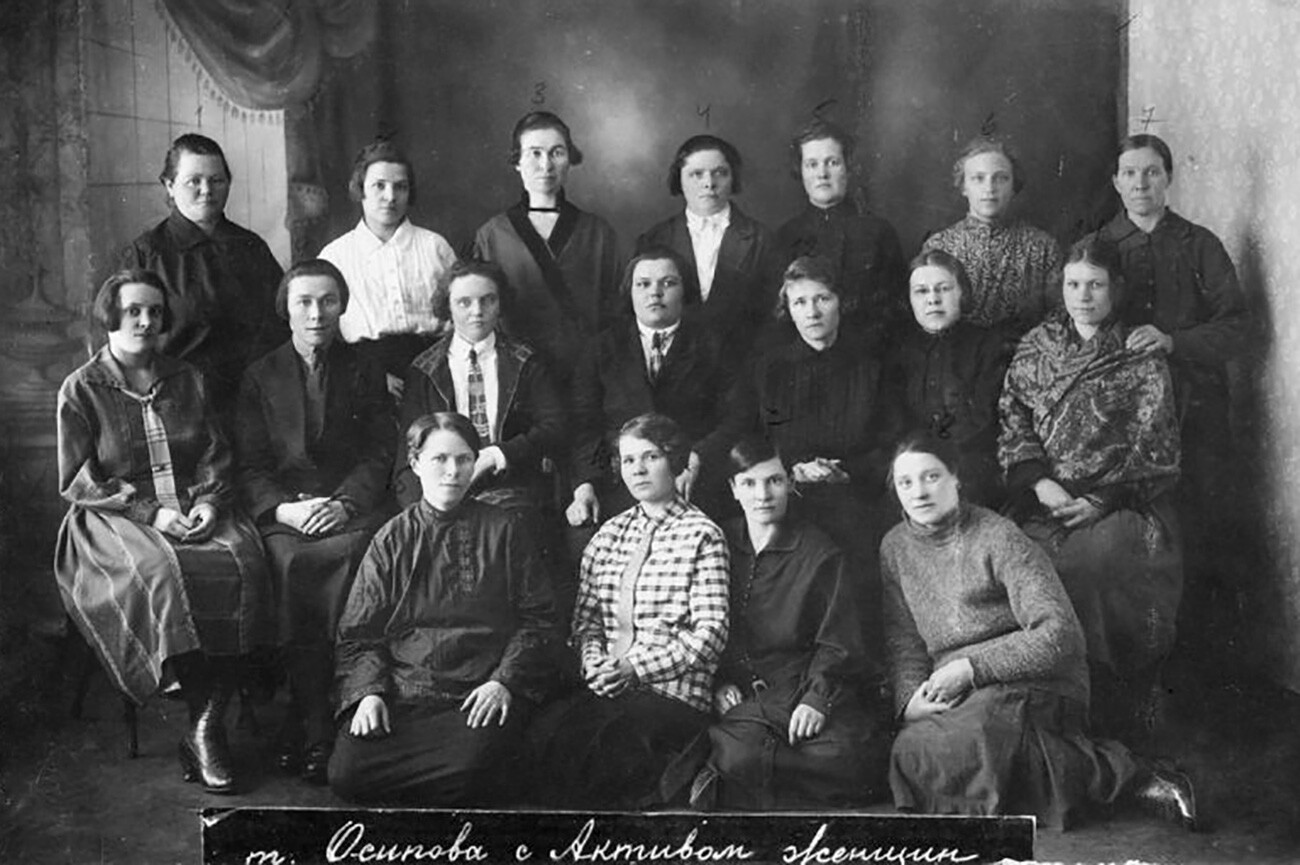

Local party's women department in Ryazan region

Kasimov local history museum/russiainphoto.ruUnder the personal control of Lenin’s wife, Nadezhda Krupskaya, specialized magazines were now being published: Rabotnitsa (‘Worker Woman’), Krestyanka (‘Peasant Woman’), Kommunistka (‘Communist Woman’). The goal of this new press was to “involve working and peasant women in the struggle for communism and in Soviet development.”

Artist Varvara Stepanova

Alexander RodchenkoIt was important that women would become equal members of society and a part of the labor force. Read more about the first Soviet women’s magazines here.

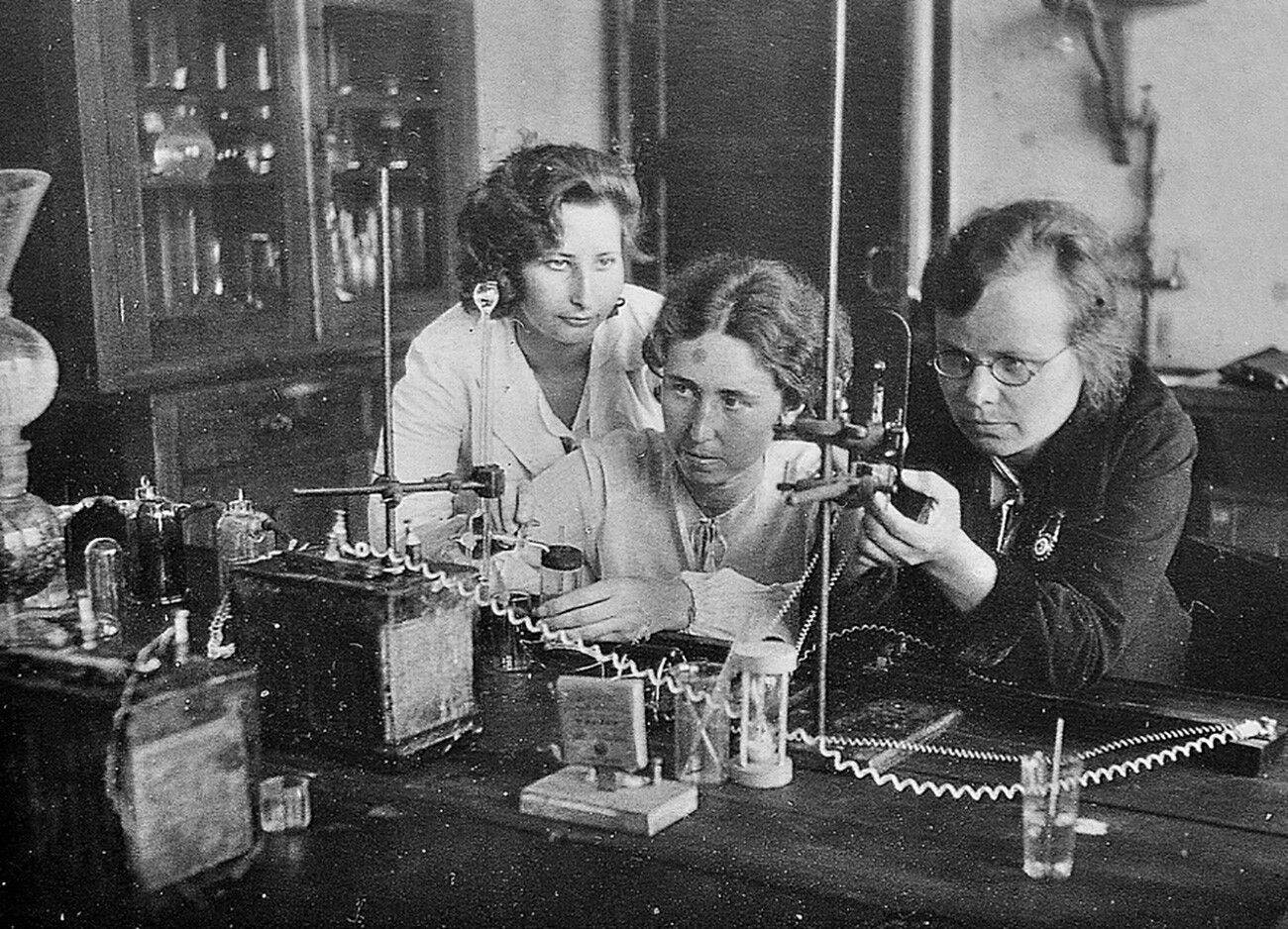

Female students in the physics lab

Sergei Propitsyn archive/russiainphoto.ruThe complex matter of working with women caused a lot of debate in the Communist Party environment itself. Zhenotdel was about to be liquidated multiple times, by transferring its functions to the Agitation and Propaganda Department. In 1923, at the XII Party Congress, which Lenin couldn’t attend, due to illness, concerns were raised about the emergence of “feminist biases”. “Such biases could propagate the creation of such special societies that, under the flag of improving the everyday-life positions of women, in reality, would lead to the alienation of the female part of the labor force from the class struggle,” the stenographic notes of the Congress cited Bolshevik Pyotr Smidovich.

Female miners

Georgy Zelma/SputnikHowever, back then, it was proposed to integrate women into party work even more, to strengthen women’s labor unions, to create an institute of communist instructors who would involve women in employment and labor protection.

Stalin, as well, often retracted back to the women question in his speeches; he said that women are the most oppressed of the working people and, at the same time, women amount to half of the population, so it’s important that they become a labor reserve and stand FOR the working class – only then it could achieve victory over the bourgeoisie.

Nonetheless, by the end of the 1920s, Stalin decided that “the ‘women’ question is fully and finally resolved” and ordered the dissolution of Zhenotdel. However, women’s councils remained in enterprises; also congresses and conferences of women continued, including international ones.

Woman at the lathe

N.Skryabin/MAMM/MDF/russiainphoto.ruIn 1941, the ‘Antifascist Committee of Soviet Women’ was founded, which continued its work even after the war; its main task was to show guests from overseas what kind of equality the USSR possessed. After the war, women, who fought against the Nazis along with men and showed unbelievable heroism, were definitely no longer considered the “weaker” sex.

Dear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox