Magazines for women had been published in Tsarist Russia, too, but they covered very specific topics: They were about fashion, society news, needlework and housekeeping or published the latest literary offerings. They only touched on important social issues in passing. But, these magazines were only accessible to and read by a fairly narrow circle of educated women. Everything changed after the fall of the monarchy, however.

After the 1917 Revolution, the Bolsheviks declared that their mission was to bring literacy to the broad masses and founded a mass media, which the Bolshevik Party took under its control and used for propaganda purposes. A separate resolution was issued on the “need to step up party control of the women’s press”. The Bolsheviks got rid of magazines that offered advice to housewives. The aim of the new press was to “enlist women workers and peasant women into the struggle for Communism and Soviet construction”. To the Bolsheviks, it was important that women became equal members of society and part of the workforce.

The majority of the magazines were published under the supervision of Nadezhda Krupskaya, the wife of the leader of the Revolution, who chaired the political education committee at the Ministry of Education and was responsible for all agitation and propaganda work, as it was known. The magazines published articles by prominent women revolutionaries Inessa Armand and Alexandra Kollontai and Lenin’s sister Anna Ulyanova-Elizarova, as well as politicians, including Anatoly Lunacharsky, the first People’s Commissar for Education and Lenin’s personal secretary and Vladimir Bonch-Bruyevich, member of the editorial board of the ‘Pravda’ newspaper.

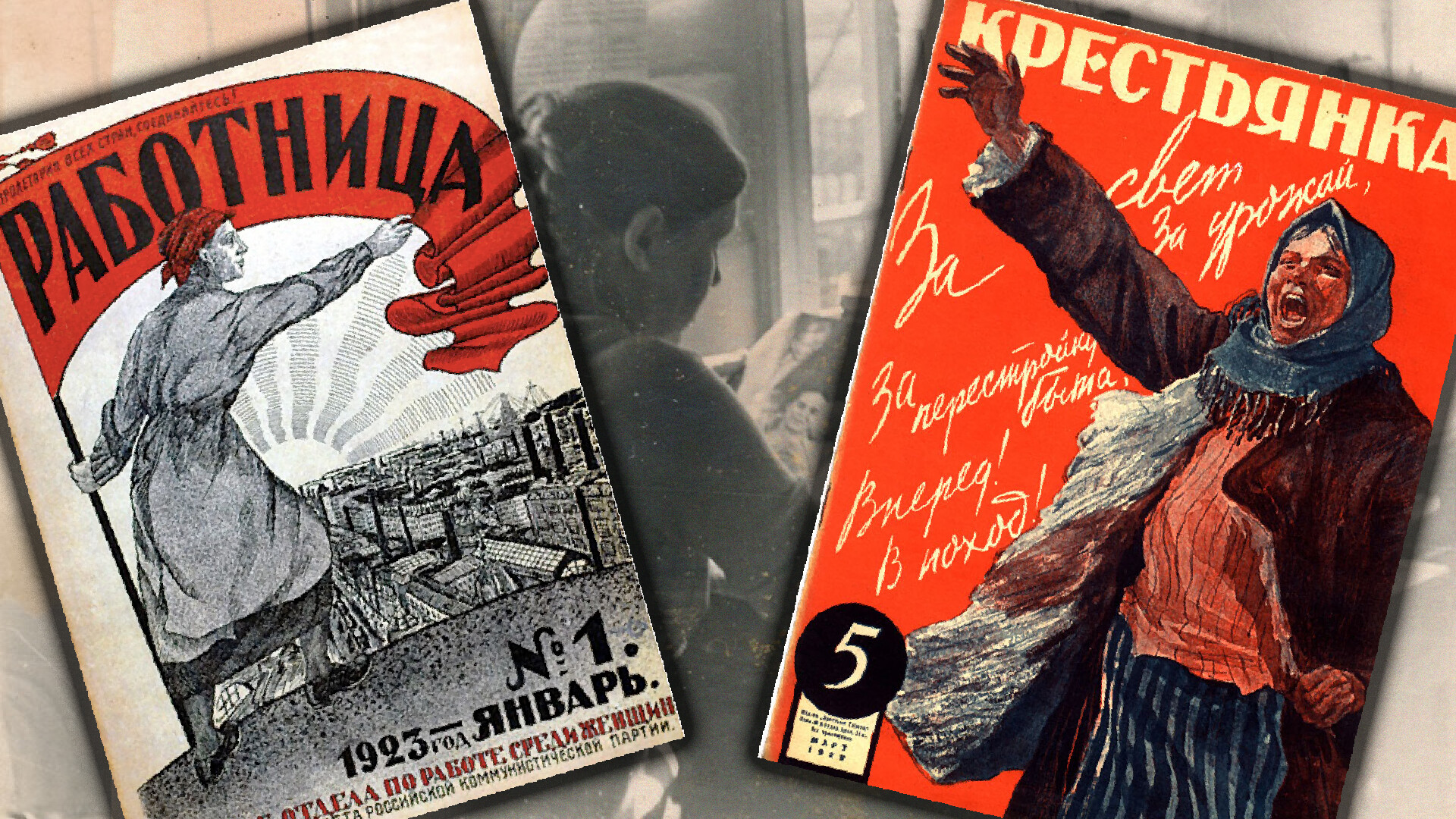

The following are just some of the magazines published specifically for women.

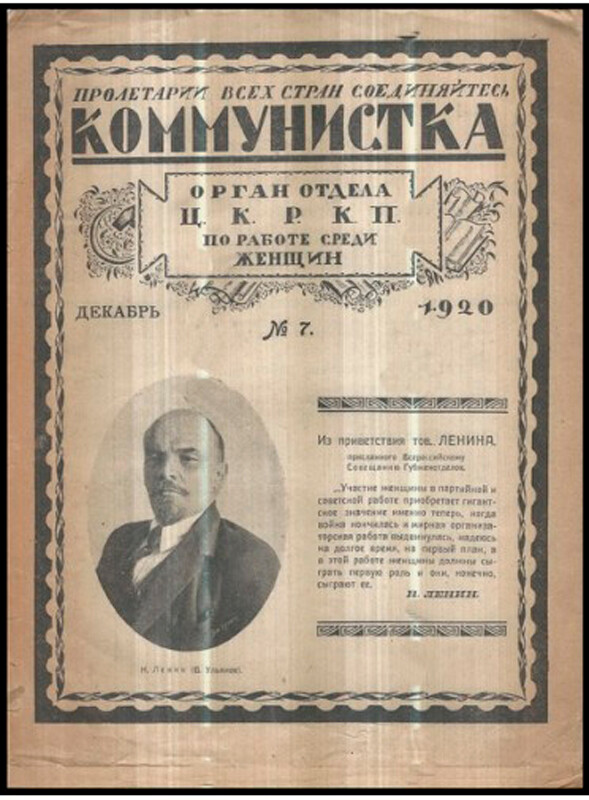

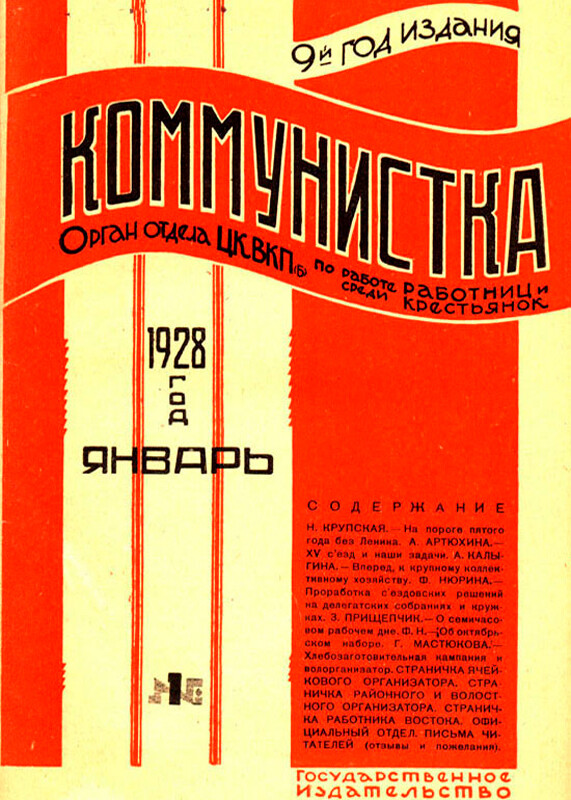

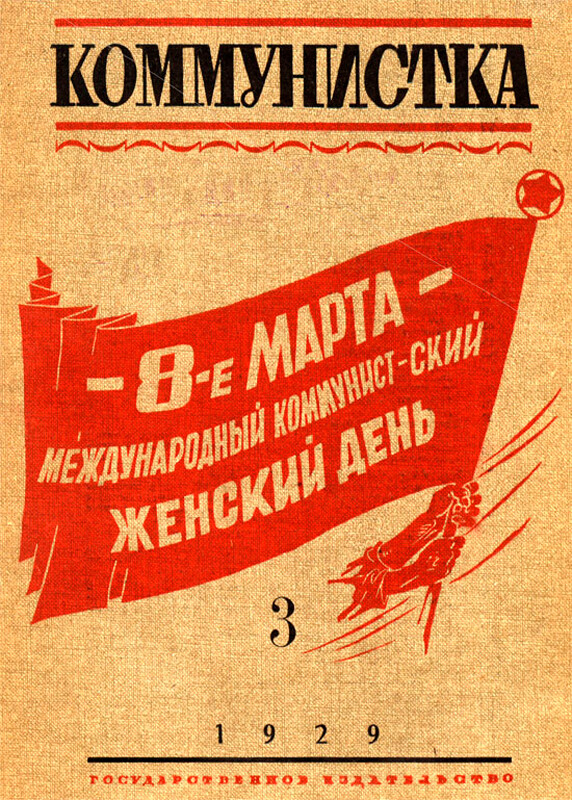

This was a political magazine and the press organ of the Bolshevik Party’s Zhenotdel (‘Women’s Department’). It had a relatively small print-run - between 20,000 and 30,000 copies were printed for a single issue from 1920 to 1930, until the Zhenotdel was abolished by Stalin.

December 1920

Archive imageThe magazine’s mission was the political education of the Party’s women members. It described how women could carry out propaganda work by themselves or how they could become a leader or train new party cadres. Historian of journalism Elena Kolomiytseva lists examples of some of the columns that featured in the magazine - ‘Issues of Organization’, ‘Issues of Propaganda’, ‘Issues of Communist Education’; and some typical headlines - ‘Strengthening the growth of the Leninist Party’, ‘Adopting a class approach in work’, ‘Preparing cadres of atheists’ and ‘Being more decisive in promotions to leading roles’.

January 1928

Archive image‘Kommunistka’ also drew up a general blueprint for the women’s press, defined its mission (“the Communist education of women”) and identified which audiences needed targeted publications - peasant women, women workers and the female partaktiv (‘party activists’). Also, ‘Kommunistka’ gave advice on how to run such magazines and called for correspondents to be enrolled from among workers and peasants to write articles for them.

March 1929

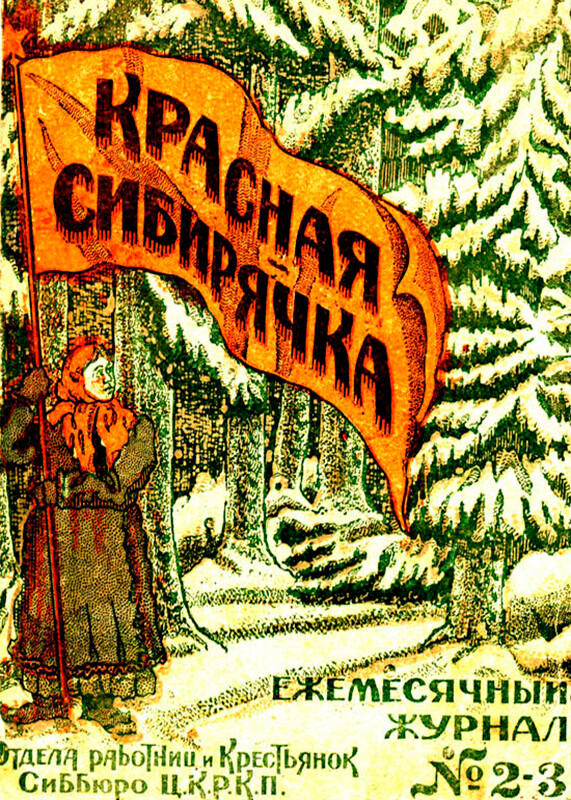

Archive imageIt was also decided to set up separate magazines in the regions. As a result, there were many clones such as ‘Krasnaya Sibiryachka’ (‘The Red Siberian Woman’), ‘Truzhenitsy Severnogo Kavkaza’ (‘Female Workers of the North Caucasus’) and others.

"Krasnaya Sibiryachka" magazine (The Red Siberian Woman)

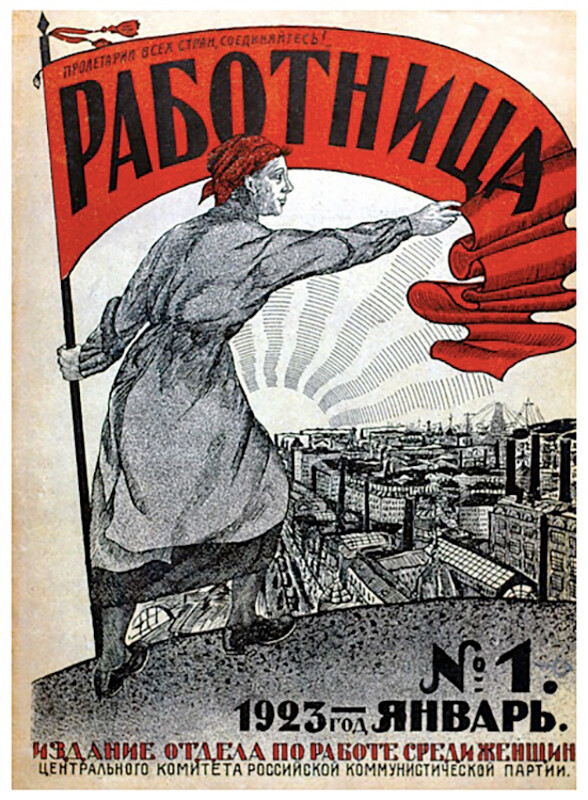

Archive imageVladimir Lenin instituted the publication of the first proletarian magazine for women, titled ‘Rabotnitsa’, as early as 1914 with the aim of “defending the interests of the women’s labor movement”. It was closed down by the tsarist police, but publication resumed after the Revolution. The magazine wrote about the importance of “fulfilling the behests of (Vladimir) Ilyich (Lenin)” and about Communist education. But, the main topics were linked to labor issues.

May 1923

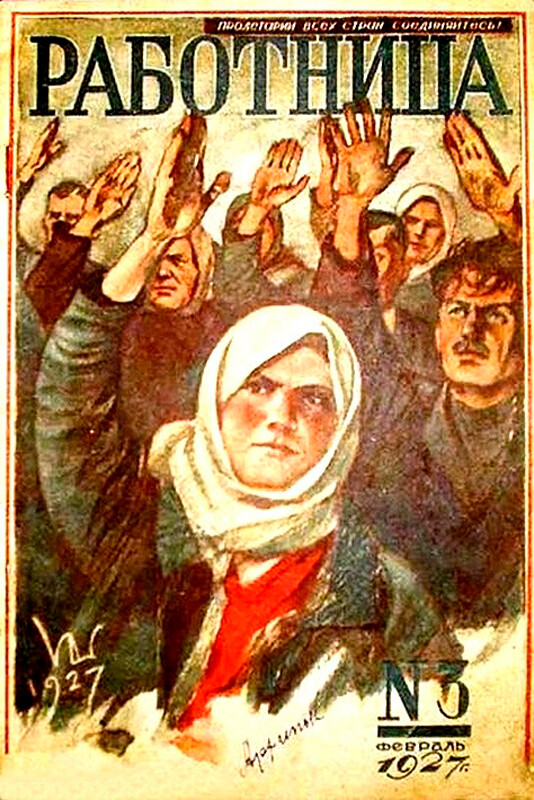

Archive imageThe magazine wrote about heroines of production and about professions that women could go into (for instance, one issue of the magazine advised readers to take a closer look at becoming a machine fitter, which does not require a lot of physical strength). Advice was also offered on comfortable work clothes, the harm of high heels and other topics.

February 1927

Archive imageOne of the magazine’s most important themes was the revolution in women’s everyday lives - women needed to free themselves from male and family “servitude” and become builders, in their own right, of Communist society and of a “great and new life”.

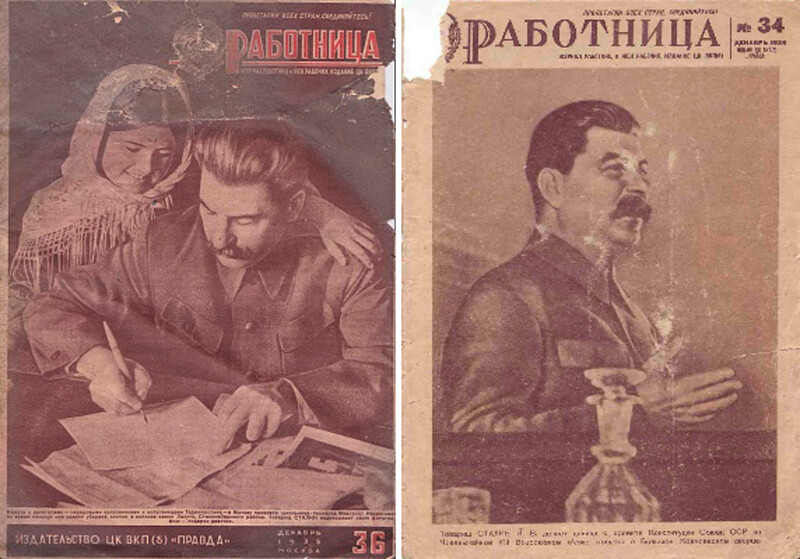

December 1935 and 1936 - Stalin on the cover

Archive image“Intellectual growth is impeded by petty cares, pots and pans, kneading troughs, slop pails and other detestable things. By casting all that aside, women would make rapid headway and would feel completely free and happy,” Nadezhda Krupskaya wrote in ‘Rabotnitsa’ in 1925.

In 1917, the magazine had a print-run of around 30,000, which continually increased: In 1941, it was 425,000, reaching a whopping 23 million by 1990.

August 1956

Archive imageMoreover, it is one of the few early titles that is still published today.

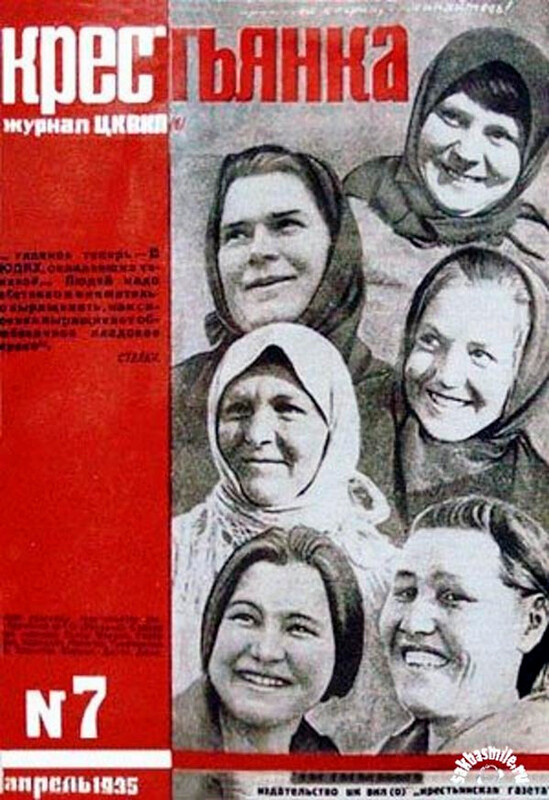

‘Krestyanka’ magazine was published from 1922 to 2015 and its print-runs numbered in the millions - by 1989, 21 million copies were being printed for a single issue. The mission of the magazine was “activism among peasant women, the promotion of Communist ideas and the instilling in the minds of peasant women of essential knowledge for their everyday life and work”.

March 1929

Archive imageThe magazine wrote about how a household should be run, how to carry out farm work and how to bring up children. In addition, it described how peasant women in other places lived and how to make the lives of working people easier. Peasant women were also told how important it was to increase bread grain production - and what was needed to achieve this.

April 1935

Archive image‘Krestyanka’ also published fictional stories about women - with the best Soviet authors, from Maxim Gorky to Alexander Tvardovsky, writing specially for the magazine. There was also a “Humorous Page” which, in poetic form, poked fun at the old ways and at offenders against the new order.

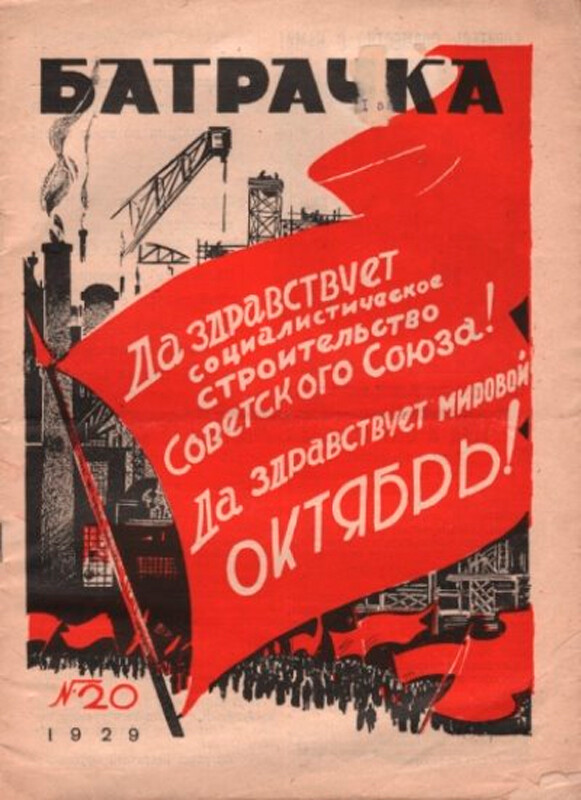

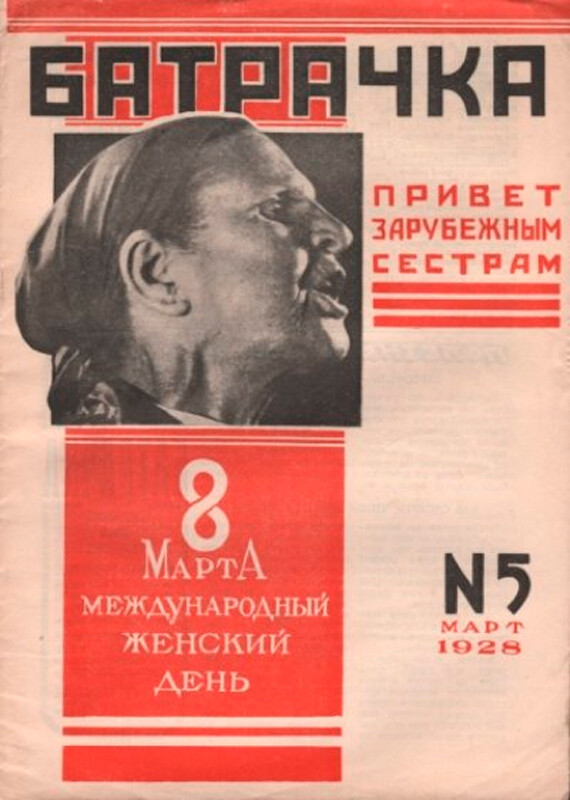

‘Batrachka’ magazine, which was published after the death of Lenin, from 1925 to 1929, was similar, in some ways, to ‘Krestyanka’. It was circulated among female agricultural and forestry workers. Subscriptions to the magazine increased from year to year and the print-run rose from 10,000 to 40,000.

October 1929

Archive imageThe magazine had a short life partly because the very idea of a batrak - a hired laborer - only existed in the early years of the USSR and in the period of the New Economic Policy (NEP).

May 1928

Archive image‘Batrachka’ contained articles dealing with women’s work and the role of women in society. It promoted the idea that women should primarily serve the interests of the proletariat and communism rather than the family.

March 1928

Archive imageThe magazine also carried articles with advice on looking after children, basic health issues and the prevention of sexually-transmitted diseases. It was targeted at poorly educated female rural workers, so they were also told what syphilis was, for instance, and instructed on the dangers of home-distilled vodka.

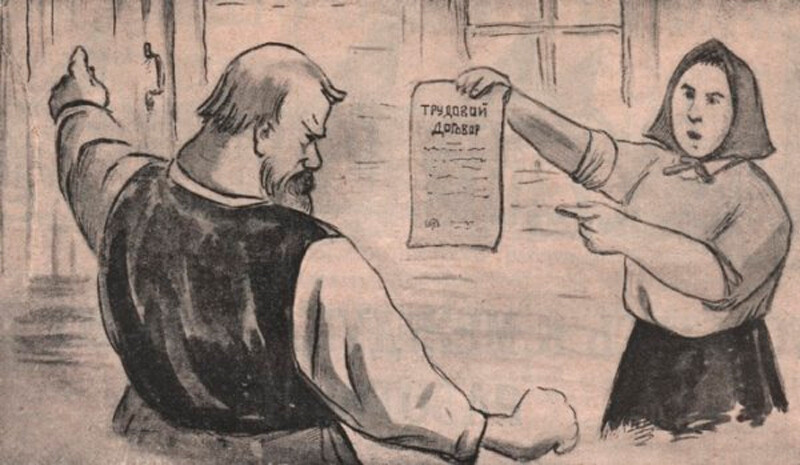

Illustration titled "Employment Contract", 1925

Archive imageDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox