Diogenes in Dixon, Krasnoyarsk Krai

Vladimir Medvedev/TASSIn 1974, Soviet authorities decided to revive an ambitious Stalin-era construction project, the Baikal-Amur Mainline. Thousands of young Soviet people head off to develop new lands to lay rails in the brutal, untamed Far North.

Temporary wooden houses were built for them, insulated in a special way against severe frosts. However, there was one serious problem: the rectangular box of dwellings could be covered up to the roof with snow overnight. And, because of this, sometimes, people could barely get out of their houses!

Inside a cistern

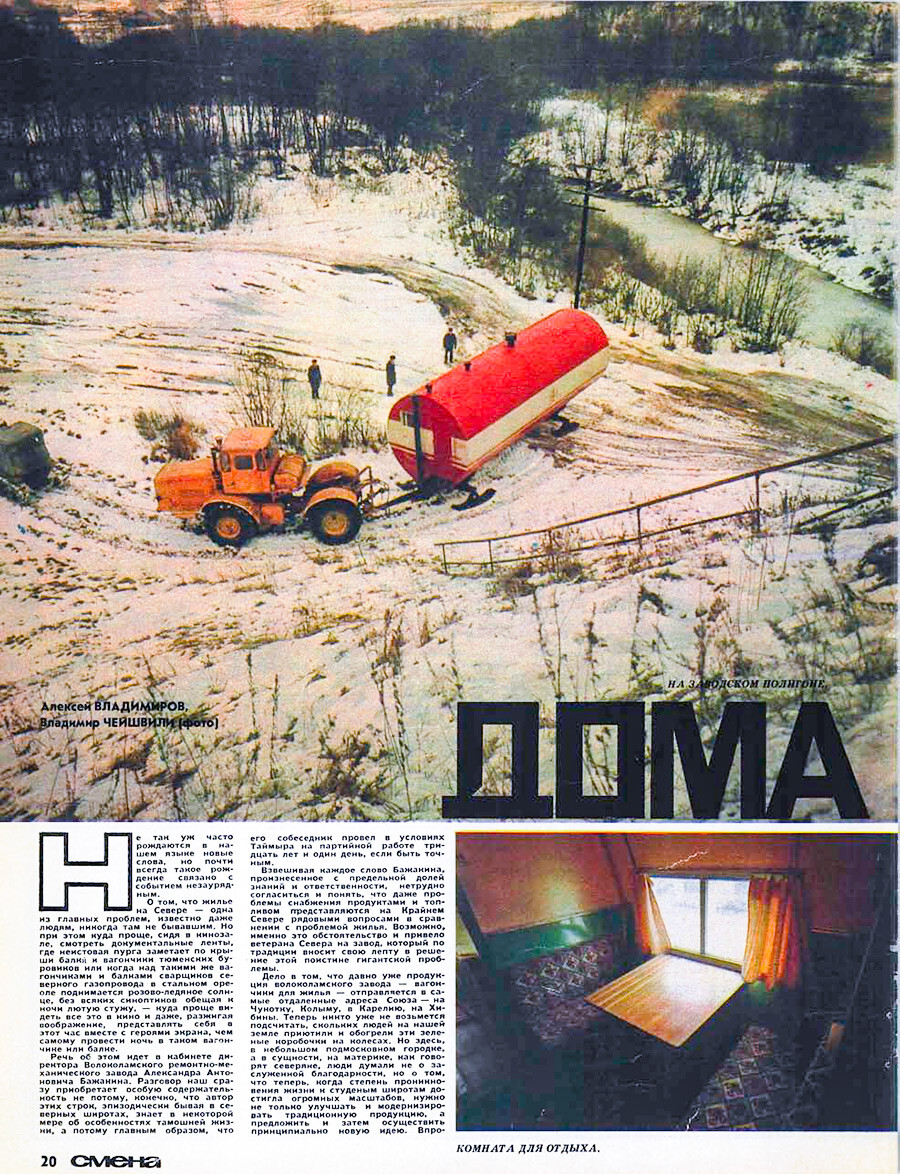

Baikal-Amur Mainline History MuseumTo solve this problem in the Far North, Soviet constructors came up with an innovative dwelling, the ‘All-Metal Unified Block’ (‘TSUB’). The futuristic ‘Tsubik’, as they were lovingly nicknamed by the people of the Baikal-Amur Mainline, became a real salvation. They were also easy to transport from place to place and install. The metal construction was very light, but, at the same time, strong and durable.

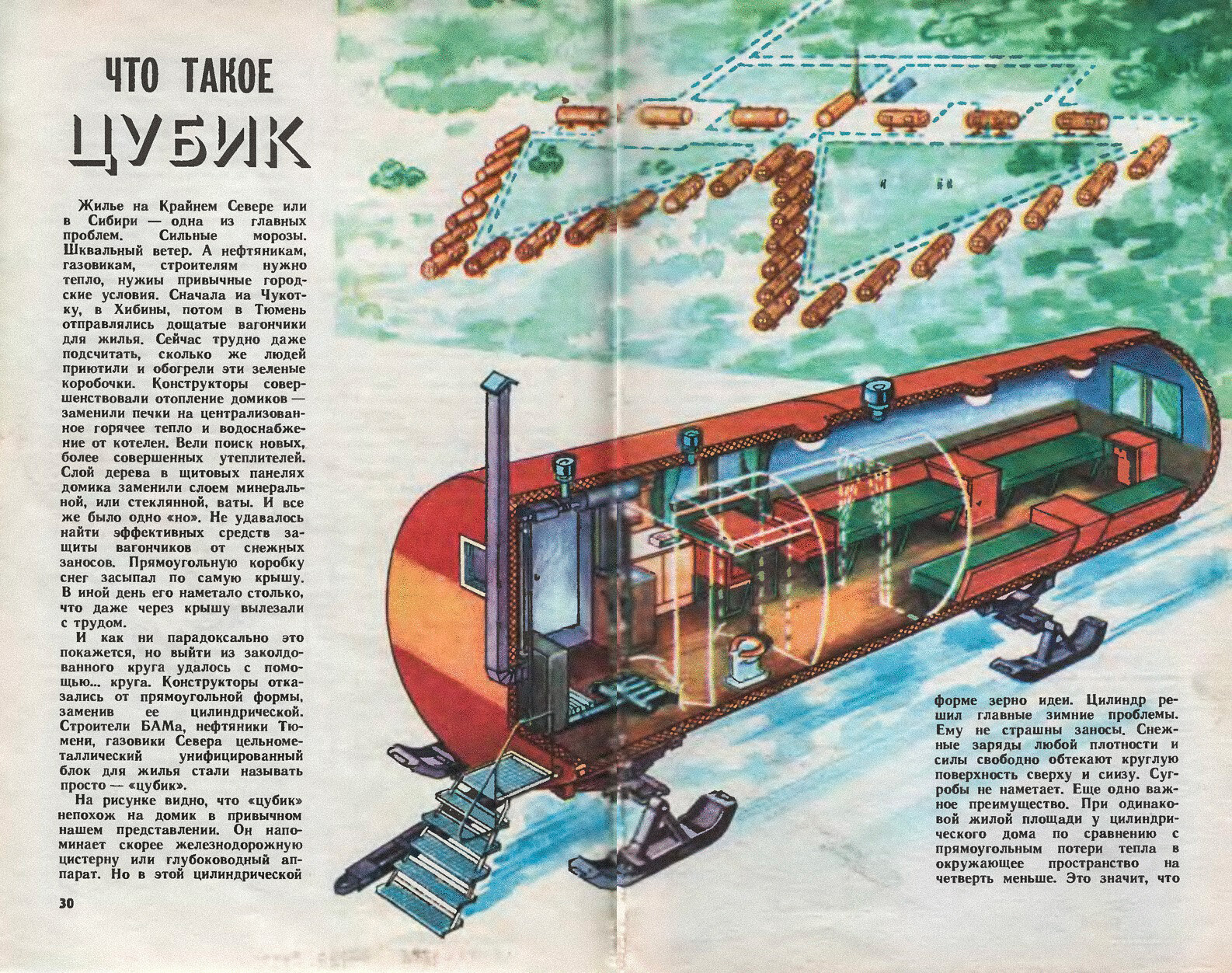

"What is Tsubik?" Pages from a Soviet magazine

"Yuny Technik" (No. 7, 1976)The cylindrical shape solved the main problem, the ‘TSUBs’ were no longer getting covered with snow and it would no longer accumulate on the roof. In addition, such "cisterns" kept heat in much better than the ordinary wooden houses.

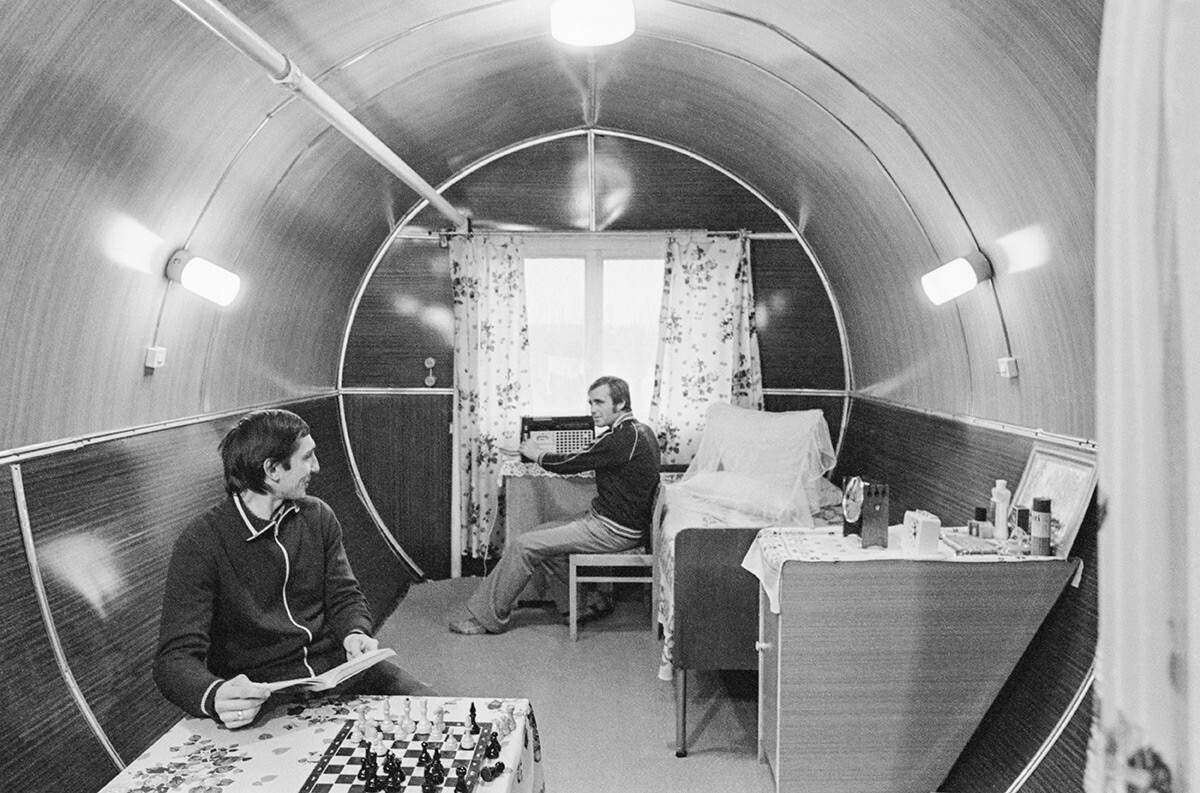

There were hundreds of such dwellings along the Baikal-Amur Mainline construction. Sometimes, whole streets of ‘Tsubiks’ appeared. They could be connected to each other and heat could be supplied centrally from one boiler house.

"Houses". A page from a Soviet magazine

"Smena" No. 5 (1147), March 1975Gradually, this experience spread to other remote areas with harsh climates, such as Chukotka and Krasnoyarsk Krai. People continued to live in them even after permanent housing had been built.

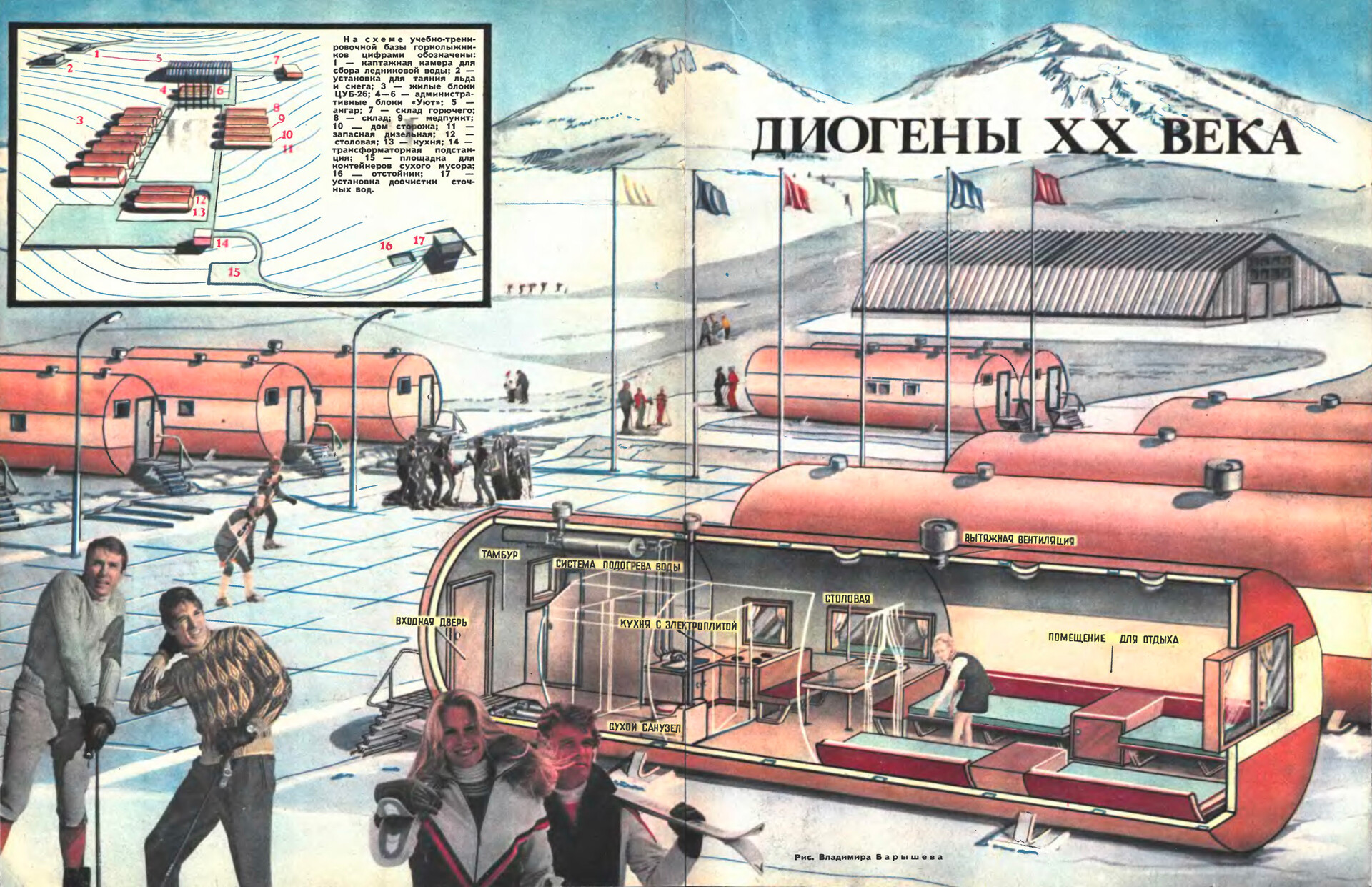

In the 1970s and 1980s, Soviet magazines wrote enthusiastically about ‘Tsubiks’ and joked that they were "Diogenes of the 20th century" living in jars.

"Diogenes of the 20th century". Pages from a Soviet magazine

"Tecnhika molodezhi" (No. 9, 1980)But, these “barrels” were not simple. Measuring nine meters in length and three meters in diameter, they were equipped with absolutely everything necessary for life. In addition to sleeping areas, there was a dining room, a kitchen with an electric stove, a dry toilet, a water heating system and an entrance place separated from the rest of the space, so that the cold from the outside would not penetrate into the living space.

Cistern houses in a forest

TASSDespite all the benefits, this type of housing was, nevertheless, still only temporary. The Soviet authorities wanted to create a permanent habitat for people along the Baikal-Amur Mainline and other places where these “barrels” had been placed. Therefore, in time, there was no longer any need for ‘Tsubiks’ as living apartment buildings and a full-fledged infrastructure for life were being built.

Pipeline builders in their house

V.Kozhevnikov/TASSIt was supposed that ‘Tsubiks’ would appear in other hard-to-reach places, where it was difficult to build anything, even on Mount Elbrus. But, in the 1990s, production was stopped. The metal structures fell into disrepair over time and ended up in a scrap metal graveyard. Although, to this day, you can still find a rusty cistern on some dacha plots, where sometimes people even sleep still!

An authentic “barrel” can also be seen today in the Museum of the Baikal-Amur Mainline History in Tynda, where there is an exposition devoted to the everyday life of the mainline builders.

TSUB with a display about TSUBs

Baikal-Amur Mainline History MuseumThe life-size recreated “barrel” can also be seen in the ‘Stations and Cities. Architectural Heritage of BAM’ exhibition at the State Historical Museum.

Inside a revived TSUB at the State Historical Museum in Moscow

Ramil Sitdikov/SputnikDear readers,

Our website and social media accounts are under threat of being restricted or banned, due to the current circumstances. So, to keep up with our latest content, simply do the following:

If using any of Russia Beyond's content, partly or in full, always provide an active hyperlink to the original material.

Subscribe

to our newsletter!

Get the week's best stories straight to your inbox